SILVANA MOSSANO

Reportage udienza del 27 settembre 2021

«L’Eternit in Europa era dominata, essenzialmente, da due famiglie, una belga e una svizzera, ma i loro nomi era proibito pronunciarli; erano indicati genericamente come gruppo o azionista di maggioranza. Però, se dico gruppo belga parlo di una famiglia precisa, gli Emsens poi De Cartier (il barone Louis aveva sposato una Emsens; era stato imputato e condannato in primo grado nel maxiprocesso Eternit Uno, morto anziano alla vigilia della sentenza del processo d’Appello, ndr) e se dico gruppo svizzero parlo della famiglia Schmidheiny. In sostanza, loro erano i padroni dell’Eternit».

E’ lapidario in questa affermazione Paolo Rivella, commercialista torinese, consulente della procura nel processo Eternit Bis, che si svolge in Corte d’Assise a Novara, nei confronti di Stephan Schmidheiny, accusato dell’omicidio volontario, con dolo eventuale, di 392 casalesi, morti a causa dell’amianto. Rivella, esaminato nell’udienza di lunedì 27 settembre davanti alla Corte presieduta da Gianfranco Pezone, affiancato da Manuela Massino e dai giudici popolari, ha esposto per sei ore la sintesi di meticolose indagini, cui ha collaborato la collega Carola Mosi, fondate sulla disamina di una mole immensa di documenti, «alcuni anche trovati a Casale, recuperati nella cosiddetta “stanza segreta” dello stabilimento, in via Oggero, al Ronzone, che era stato abbandonato dopo il fallimento dell’Eternit italiana, nel 1986». Il ritrovamento di molti documenti – pare fin impossibile – era avvenuto nel 2005, a diciannove anni dal fallimento, in uffici abbandonati e nel sottotetto della fabbrica tra polvere, sporcizia e guano.

Rivella, consulente in circa trecento cause giudiziarie, aveva già fatto parte del team di esperti al maxiprocesso di Torino, all’epoca incaricato dai pm Guariniello, Colace, Panelli. Ora, l’accusa è sostenuta dallo stesso Gianfranco Colace e dalla collega Mariagiovanna Compare.

Invariato, rispetto ad allora, il collegio difensivo dell’imputato, composto dagli avvocati Astolfo Di Amato e Guido Carlo Alleva che, all’udienza di mercoledì 29 settembre, sottoporranno il commercialista a controesame, preannunciato come lungo e corposo.

In sostanza, dunque, dice Rivella, gli Schmidheiny – per attenersi all’imputato – erano i «padroni». Questo per rispondere alla domanda del pm Colace che gli ha chiesto «di ricostruire la figura del responsabile della gestione dello stabilimento Eternit di Casale in capo a Stephan Schmidheiny».

Ci vuole un po’ di storia. Fu l’austriaco Ludwig Hatschek a brevettare il materiale «eternit», composto dalla mescola di prodotti poveri come cemento e acqua, con l’aggiunta di amianto, quest’ultimo in una percentuale minima, che è ben più costosa ed è quella che gli conferisce caratteristiche importanti. Tra le altre: è molto economico e veloce nell’impiego. «Nei paesi poveri, si costruirono molte baracche di eternit: in 48 ore metti la famiglia a dormire sotto un tetto, che sarà pure velenoso nel lungo termine, ma nell’immediato ti ripara dal freddo e dalle intemperie, non meno insidiose» ha esemplificato il consulente. E così accade, ad esempio, ancor oggi in India.

LA STORIA

Hatschek usa il brevetto per sé in Austria, ma lo cede in altri Paesi. I principali utilizzatori del brevetto sono l’Eternit nell’Europa continentale, la Turner&Newall inglese e la Johns Manville negli Stati Uniti.

«In Europa – ha ribadito Rivella – l’Eternit è nelle mani dei belgi Emsens/De Cartier, degli svizzeri Schmidheiny e dei francesi Cuvelier».

In Italia, invece, per qualche decennio la situazione è un po’ diversa. Nel 1906, il giovane ingegnere Adolfo Mazza, che lavorava in Austria per le ferrovie, conobbe Hatschek e acquistò il brevetto; fondò la Eternit Pietra Artificiale Società Anonima con sede legale a Genova e, dal 1907, stabilimento a Casale, anche perché in questa zona c’erano molti cementifici e il cemento è materia necessaria per costruire le lastre di «eternit». Mazza, però, progredisce; oltre a quotarsi in Borsa nel 1917 (mantenendo il 51% delle quote), inventa anche un modo per costruire, con quel tipo di impasto, i tubi ad alta pressione. Anche Eternit svizzera prova a fare i tubi, ma non ci riesce e compra poi la licenza da Mazza.

Intanto, nel panorama europeo si costituisce la Saiac (Società associata dell’industria dell’amianto cemento) «che – secondo il consulente – fa da segretariato al “cartello” segreto per la gestione dell’amianto-cemento in regime di monopolio». Più avanti, il cartello si espande, diventa mondiale, con la partecipazione della Johns Manville, americana.

Che scopi aveva il «cartello» (che, pure, non è mai citato esplicitamente come tale)? La risposta di Rivella: «A condividere le conoscenze tecniche, a contrastare l’affermazione dei materiali alternativi (come ad esempio la plastica), a concordare prezzi e quantità controllando quindi il mercato».

Anche la Eternit Pietra Artificiale SA entra in Saiac e, nel 1949, Mazza ne è presidente onorario. Mazza, acquista anche, in società con l’imprenditore Rinaldo Colombo, la grande miniera di Balangero, l’unica in Europa, da cui si estrae amianto bianco.

Nel 1952, la famiglia Mazza cede parte delle proprie azioni, cosicché il pacchetto risulta così suddiviso: 26% Mazza, 10 % belgi, 10% svizzeri e 5% francesi. Passano altri vent’anni e, nel 1972, sono gli Schmidheiny ad acquisire la maggioranza, mentre i belgi si sfilano, perché non ci vedono un affare finalizzato a guadagnare. «E’ abbastanza vero quanto dice Stephan Schmidheiny e cioè che nell’Eternit italiana ci ha perso dei soldi, ma, del resto, l’obbiettivo, fin dall’acquisizione della maggioranza da parte di Max, suo padre, ed Ernst, suo zio, era ben altro: bloccare l’avanzata di altri concorrenti, mantenendo il controllo del mercato e, in più, gli stabilimenti italiani dell’amianto erano grandi consumatori di cemento». E quindi? «Gli Schmidheiny erano i signori del cemento in Europa», era questo l’altro grande filone delle loro attività. E quando Max Schmidheiny passò la mano ai figli, assegnò a Thomas il settore del cemento (Holcim) e a Stephan quello dell’amianto (Eternit).

LA GESTIONE SVIZZERA

«A partire dal 1972 la gestione è nelle mani del gruppo svizzero attraverso propri uomini di fiducia, che hanno l’obbiettivo preciso di “ridimensionare il potere decisionale del Comitato di direzione della Eternit italiana”». Dichiarazioni di cui il consulente ha fornito precise tracce nella disamina di verbali e documenti.

E che succede in Italia dal 1972 al 1986?, domanda il pubblico ministero Colace.

«Prima dominano Max ed Ernst Schmidheiny e, dal 1976, subentra Stephan che, già dal 1975, era amministratore delegato di Eternit svizzera. Nel ’76, ha in capo la gestione totale di Eternit che include il controllo di Eternit italiana: quest’ultima divenne a tutti gli effetti una filiale della Eternit svizzera, la quale controllava tutto, persino la percentuale delle miscele!».

Nel 1978, subentrano problemi: intanto «il mercato edilizio entra in crisi e poi comincia a diffondersi la consapevolezza che l’amianto è nocivo, molto nocivo» ha spiegato Rivella. E ha citato lo scienziato Irving Selikoff che, già nel 1964, alla Conferenza mondiale dell’Accademia delle Scienze di New York, aveva messo in guardia sulla correlazione tra fibra di amianto e cancro; «nel 1973, “The New York Times ha pubblicato un’ampia intervista a Selikoff che ha ribadito gli stessi argomenti con forza» ha spiegato il consulente, mostrando il giornale, di cui fu trovata una fotocopia sempre tra i documenti reperiti nella «stanza segreta» all’Eternit casalese. C’era, allegata, una lettera, a firma di un tal E. Demichelis, che era stato prima dirigente di produzione a Casale, poi direttore del marketing nella sede legale di Genova. Rivolgendosi ai massimi dirigenti, scriveva riferendosi all’intervista: «Per noi è un disastro. E quando me ne sono andato da Casale la situazione era drammatica». Ma chi sollevava toni allarmistici non era ben visto. «Selikoff fu aspramente criticato e dileggiato a livello mondiale – ha riferito Rivella – e anche Demichelis fu quietato».

Il pm sollecita chiarimenti: «Quindi c’era ai vertici della società la conoscenza della correlazione tra amianto e cancro?».

Ci sono studi già negli anni Cinquanta (qualcuno pubblicato nonostante pressioni contrarie, qualcuno invece tacitato); il consulente, tanto per esemplificare, ha riferito che il World Trade Center fu costruito fino a un certo livello impiegando manufatti di amianto, da un certo piano in su si sono usati materiali alternativi, privi di amianto».

RIUNIONE DI NEUSS

Stephan Schmidheiny la consapevolezza ce l’ha. Nel 1976, «a giugno, ha convocato a Neuss i suoi massimi dirigenti per far presente che è stata riscontrata l’esistenza di effetti cancerogeni e quindi, riflette l’imprenditore, “dobbiamo migliorare la qualità dell’aria e mettere al riparo i lavoratori dai rischi dell’amianto”. Dice cose sensate ed encomiabili» sottolinea Rivella.

E pertanto, a fronte di quel buon proposito, che cosa suggerisce? «Sollecita un progetto per lo studio di provvedimenti che vanno presi dalle aziende».

A tutela di chi? «Nei verbali sono contenute le preoccupazioni espresse: “I sindacati minacciano di mettere sotto tiro l’amianto anche in futuro”, e ancora “L’amianto viene considerato una sostanza pericolosa e la concorrenza ne approfitta”». E’ dunque questo il problema che bisogna risolvere. E così si introduce «il tema dell’uso controllato dell’amianto», a significare che, se lo si utilizza con adeguate accortezze, non fa male. Nei Paesi dove è stato bandito, non ci si crede più da un po’, ma in certi Stati, dove a tutt’oggi la fibra è impiegata, l’argomento continua a essere divulgato. E continua a reggere le sorti delle industrie dell’amianto.

«AULS 76»

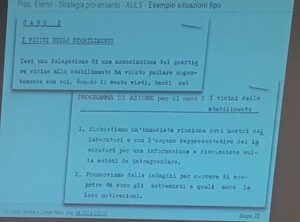

Il consulente ha illustrato alcuni filoni su cui si è concentrata la «Politica e strategia del gruppo svizzero». Rivella l’ha definita «offensiva di propaganda mediatica» con lo scopo di tutelare l’industria dell’amianto e di attenuare o soffocare i clamori determinati dalla sempre più diffusa consapevolezza della pericolosità della fibra.

«Non fatevi prendere dal panico»: è uno degli slogan contenuti in «Auls 76», un rapporto operativo, uscito dal seminario di Ermatingen, tenutosi a novembre 1976, solo cinque mesi dopo Neuss (la riunione convocata a giugno da Schmidheiny da cui i suoi massimi dirigenti uscirono «choccati»: «parole sue» ha specificato il consulente).

Auls 76 è un manuale a tutti gli effetti, contenente indicazioni precise cui devono attenersi i dirigenti chiamati via via a rispondere a interrogativi posti dai lavoratori, dai sindacati, dagli amministratori locali, dai giornalisti, dai cittadini. E’ elencata un’ampia rosa di possibili domande e le precise risposte e rassicurazioni da dare.

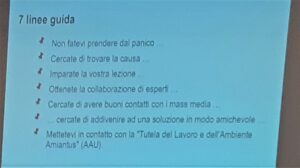

L’elenco delle cose cui i dirigenti devono attenersi scrupolosamente è articolato in sette punti.

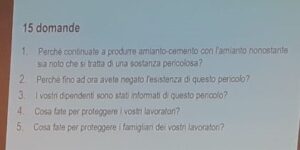

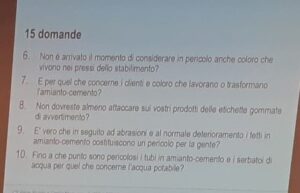

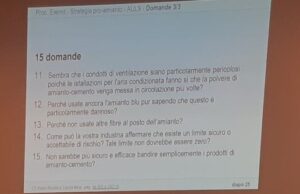

Poi c’è un elenco di 15 domande possibili.

Poi c’è un elenco di 15 domande possibili.

E per ogni interrogativo c’è la risposta che il dirigente deve imparare a memoria perché è quella che si deve fornire.

«Auls» viene applicato scrupolosamente e funziona, tanto è vero che nella corrispondenza riservata tra Schmidheiny e l’amministratore delegato Luigi Giannitrapani (lettere che vengono recapitate a una esclusiva casella postale, estranea a punti di recapito della posta normale), il primo si complimenta con il secondo: «Sono contento che Ausl sta dando i suoi frutti».

Anche a livello internazionale, tutto il settore amiantifero avverte l’incertezza del futuro e il peso del dilagare sempre più ampio delle preoccupazioni legate ai rischi di malattia causata dall’amianto. L’analisi è pignola, non trascura i dettagli. «Le autorità, in diversi Stati, pretesero l’applicazione di etichette su cui fosse scritto che l’amianto nuoce alla salute – ha ricordato Rivella -. In che lingua scriverlo? L’immagine stilizzata di un teschio sarebbe stato simbolo universale». Mammaipiù, perché la raffigurazione avrebbe creato più apprensione e agitazione di una scritta magari edulcorata.

A proposito di appropriatezza di scrittura, la definizione «prodotto di cemento amianto» fu sostituita dal preferibile «prodotto in fibrocemento», nascondendo la parola amianto, perché era quella evocatrice del rischio cancerogeno.

I «TOUR D’ORIZON»

Della strategia fanno parte anche i «Tour d’Orizon», riunioni ristrette a cui partecipano i maggiori gruppi mondiali in condizioni di assoluta riservatezza. Rivella ha riferito che le convocazioni degli americani erano rigorosamente orali, perché non rimanesse traccia, dal momento che negli Usa la legislazione era molto più severa e penalizzante. «Si fanno analisi dei mercati, delle prospettive a medio e lungo termine, della consapevolezza del pericolo e, sempre più presente, è il tema del rapporto tra amianto, ambiente e salute».

Ma, vista la premessa introduttiva del consesso di Neuss, – cioè il proposito di migliorare la qualità dell’aria e di salvaguardare i lavoratori dal rischio della fibra -, come si è mosso Schmidheiny? «Soldi per la sicurezza non ne ha spesi molti – ha spiegato il consulente -: per Casale ho trovato traccia di meno di quattro miliardi di lire, ma indicati in un prospetto generico, in cui le varie voci sono affiancate a cifre arrotondate grossolanamente, senza la corrispondenza di una contabilità precisa dedicata alla sicurezza».

VERSO LA CHIUSURA

La Eternit spa in Italia va in amministrazione controllata nel 1984 e fallisce il 4 giugno 1986.

La fabbrica del Ronzone viene abbandonata così com’è: due giri di chiave al cancello e un concentrato immane di polvere che fuoriesce, per anni, dagli squarci e dai pertugi che, via via, intemperie e degrado del tempo inevitabilmente producono.

«Schmidheiny conservò la preoccupazione della concorrenza che avrebbe avuto riflessi sul mercato europeo – ha spiegato il commercialista -. Così, fece pervenire un’offerta al curatore fallimentare perché vendesse il marchio Eternit italiano e una macchina per fare lastre alla Eternit francese, in modo da non lasciare campo libero a eventuali concorrenti (ad esempio i Pesenti)».

STRATEGIA POST FALLIMENTO

L’imprenditore svizzero si è rivolto alla società milanese di pubbliche relazioni di Guido Bellodi, affidandogli l’incarico di creare una rete protettiva attorno al suo nome. «Si ha traccia dell’attività svolta tra il 1984 e il 2005, anno in cui tutta la documentazione fu sequestrata dalla procura della Repubblica di Torino. Poi se sia continuata l’attività di Bellodi non so» ha dichiarato il consulente. In base alla sua ricostruzione documentale, i compensi versati da Schmidheiny a Bellodi stanno tra un milione e un milione e 300 mila euro per il quadriennio tra il 2001 e il 2005. Non si sa per il periodo compreso tra il 1984 e il 2005, perché non si è riusciti a recuperare le parcelle, in quanto la società ha cambiato alcune volte il nome.

Il professionista milanese stilò un nuovo più specifico manuale (che negli atti processuali viene definito «Manuale Bellodi», considerato la «Bibbia» dagli stessi promotori e fruitori). Contiene precise norme di comportamento su come deve essere gestita l’informazione, mantenendo la focalizzazione in primis sull’Eternit italiana, al più sfiorando la Becon svizzera (in cui sono confluite tutte le pendenze di Eternit; tutt’ora attiva, è la società che gestisce i risarcimenti con i cittadini), ma con la massima cura a evitare che l’attenzione sfiori la società di vertice e, meno che mai, il nome di Stephan Schmidheiny.

Bellodi coordina una fitta attività di monitoraggio – anche con l’utilizzo di «antenne», tra cui una giornalista free lance casalese, cui, in modo più prosaico, Rivella ha attribuito una «attività di spionaggio o, se volessimo essere più diplomatici, di intelligence», soprattutto in seno al sindacato) –; monitoraggio sui processi, la stampa, le associazioni di lavoratori e famigliari delle vittime e si predispongono le transazioni per scongiurare il più possibile i processi. Si sfugge, invece, alle bonifiche che sarebbero costate «cifre stellari» (ebbero a riferire alcuni testi, in passato). Ed, effettivamente, gli enti pubblici che se le sono sobbarcate non possono che confermare.

Obbiettivo fondamentale della campagna di pubbliche relazioni era contenere il «rumor» a livello locale, evitando che sconfinasse a livello nazionale e internazionale.

Poi, però, è arrivato internet e, attraverso la rete informatica, ha preso forma e forza quella che sempre Pesce ha definito la «multinazionale delle vittime dell’amianto» che fronteggia la «multinazionale degli amiantiferi». E, come ha ammonito Romana Blasotti Pavesi, storica presidente dell’Associazione di famigliari e vittime, «noi siamo più tanti di voi».

UDIENZA DI MERCOLEDì 29

Domani, mercoledì 29 settembre, Rivella si sottopone al controesame dei difensori dell’imputato.

Nella foto in apertura, Paolo Rivella e Carola Mosi

Traduzione a cura di Vicky Franzinetti

SILVANA MOSSANO

27 September 2021

“Eternit in Europe was essentially dominated by two families, the Belgian and the Swiss one, but it was forbidden to speak their names; they were referred to generically as a group or majority shareholders. However, if I referred to the Belgian Group, I was talking about a specific family, the Emsens first and then the De Cartier[1] and if I said Swiss group, I was talking about the Schmidheiny family. In essence, they were the Eternit masters.

Paolo Rivella, an Turin registered accountant and prosecutor’s expert witness in the Eternit Bis trial against Stephan Schmidheiny (who is accused of the deaths, wilful murder, of 392 people from Casale, Italy, who died from asbestos) offers a very clear and brief statement. Rivella, was heard in the today’s hearing Monday, the 27th of September, in the Court presided by Gianfranco Pezone, assisted by Manuela Massino and the popular judges (jury). For six hours he presented the summary of meticulous investigations, carried out with his colleague Carola Mosi. Investigations were based on the examination of a huge amount of documents, “some also found in Casale, recovered in the so-called “secret room” of the plant, in Via Oggero, Ronzone, which had been abandoned after the bankruptcy of the Italian Eternit, in 1986“. The discovery of many documents – it seems impossible – took place in 2005, nineteen years after the bankruptcy, in abandoned offices and in the attic of the factory among dust, dirt and guano or bird excrements.

Rivella has worked as an expert witness in around three hundred court cases, and had already been part of the team of experts at the first Turin trial, at the time appointed by prosecutors Guariniello, Colace and Panelli. In this trial, the prosecutors are Gianfranco Colace and Mariagiovanna Compare.

The defence team of the defendant has not changed since then: lawyers Astolfo Di Amato and Guido Carlo Alleva announced they will cross examine Rivella at length at the hearing of Wednesday, September 29.

Prosecutor Colace asked Rivella “to describe the figure of the person responsible for the management of the Eternit plant in Casale in the hands of Stephan Schmidheiny”, and to stick to the defendant , the Schmidheinys – Rivella called them the ‘master-owners’.

It takes a bit of history: the Austrian Ludwig Hatschek patented the ‘Eternit’ material, made up of a mixture of poor products such as cement and water, with the addition of asbestos, the latter in a minimal percentage, which is much more expensive and is what gives it its main characteristics. Among others: it is very cheap and quick to use. “In poor countries, many shacks were built out of asbestos: in 48 hours you can put your family to sleep under a roof, which may be poisonous in the long term, but in the short term it protects you from the cold and the weather, which are no less insidious,” the consultant explained. This is still the case in India today, for example.

THE STORY

Hatschek used the patent for himself in Austria, but also sold it to other countries. Eternit in continental Europe, Turner&Newall in the UK and Johns Manville in the US were the main companies to purchase it. In Europe,” Rivella reiterated, “Eternit was in the hands of the Belgian Emsens/De Cartier, the Swiss Schmidheiny and the French Cuvelier.

On the other hand in Italy, the situation is a little different for a few decades. In 1906, young engineer Adolfo Mazza, who was working in Austria for the railways, met Hatschek and bought the patent; he founded the Eternit Pietra Artificiale Società Anonima with its registered office in Genoa and, from 1907, a plant in Casale, partly because there were many cement factories in the area and cement was necessary to produce “Eternit” sheets. Mazza progressed; in addition to listing the product on the stock exchange in 1917 (keeping 51% of the shares), he also invented a way to build high-pressure pipes using that type of mixture. Swiss Eternit also tried to make pipes, but failed and bought the licence from Mazza. In the meantime, Saiac (Società associata dell’industria dell’amianto cemento) was established in Europe “and – according to the consultant – acted as a secret “cartel” secretariat for the management of asbestos-cement in a monopoly regime”. Later on, the cartel expanded, became worldwide, with the participation of the American Johns Manville.

What was the purpose of the ‘cartel’ (which is never explicitly mentioned as such)? Rivella answered: “To share technical knowledge, to oppose the emergence of alternative materials (such as plastic), to agree on prices and quantities and thus control the market”. Eternit Pietra Artificiale SA also joined Saiac and, in 1949, Mazza became its honorary president. In partnership with the entrepreneur Rinaldo Colombo, Mazza also bought the large Balangero mine, the only one in Europe, from which white asbestos was extracted. In 1952, the Mazza family sold part of its shares, and the package was divided as follows: 26% Mazza, 10% Belgian, 10% Swiss and 5% French. Twenty years later, in 1972, the Schmidheinys acquired a majority stake, while the Belgians pulled out because they did not see it as a profit-making business. “What Stephan Schmidheiny says is true, that is that he lost money in the Italian Eternit, but after all, his objective had been quite different since the acquisition of the majority by Max, his father, and Ernst, his uncle: to block the advance of other competitors, maintaining control of the market and, in addition, the Italian asbestos plants were big consumers of cement. ‘The Schmidheinys were the cement lords of Europe’, that was the other major line of business. And when Max Schmidheiny handed the business over to his sons, he assigned the cement sector (Holcim) to Thomas and the asbestos sector (Eternit) to Stephan.

SWISS MANAGEMENT

“From 1972 onwards, the management was in the hands of the Swiss group through its own trusted men, who had the precise aim of “reducing the decision-making power of the Italian Eternit Management Committee””. Statements of which the consultant provided precise traces in the examination of minutes and documents. And what happened in Italy from 1972 to 1986?”, asked prosecutor Colace. ‘First Max and Ernst Schmidheiny were in control and then from 1976, Stephan took over. He had already been the managing director of Swiss Eternit since 1975. In 1976, he was in charge of the total management of Eternit which included the control of Eternit Italiana: the latter became to all intents and purposes a subsidiary of Swiss Eternit, which controlled everything, even the percentage of the mixtures”. The problems started in 1978: first of all, ‘the building market plummeted and then awareness of asbestos was harmful, very harmful began to spread,’ Rivella explained. And he quoted the scientist Irving Selikoff who, as early as 1964, at the World Conference of the Academy of Sciences in New York, had warned of the correlation between asbestos fibres and cancer; “in 1973, The New York Times published a wide-ranging interview with Selikoff who reiterated the same arguments forcefully,” explained the consultant, showing the newspaper, a photocopy of which was found among the documents found in the “secret room” at Eternit Casalese. Attached was a letter, signed by a certain E. Demichelis, who had first been production manager at Casale, then marketing director at the Genoa headquarters. Addressing the top management, he wrote, referring to the interview: ‘It’s a disaster for us. And when I left Casale the situation was dramatic’. But those who raised alarmist tones were not well liked. Selikoff was severely criticised and mocked worldwide,” said Rivella, “and Demichelis was also appeased. The prosecutor asked for clarification: “So there was knowledge of the correlation between asbestos and cancer at the top of the company? There were studies dating back to the 1950s (some were published despite pressure to the contrary, while others were silenced); the consultant, just to give an example, said that the World Trade Center was built up to a certain level using asbestos products, and from a certain floor upwards alternative, asbestos-free materials were used”.

NEUSS MEETING

Stephan Schmidheiny is aware of this. In 1976, ‘in June, he summoned his top executives to Neuss to point out that carcinogenic effects had been found and therefore,’ the businessman reflects, ‘we must improve air quality and protect workers from the risks of asbestos’. He said sensible and commendable things,’ Rivella points out. And so, in the face of that good intention, what did he suggest? “He called for a project to study the measures to be taken by companies. To protect whom? “The minutes of the meeting contain the concerns expressed: ‘The unions are threatening to put asbestos under fire in the future’, and again ‘Asbestos is considered a dangerous substance and the competition is taking advantage of it'”. This is therefore the problem that needs to be solved. This is how ‘the subject of the controlled use of asbestos’ was introduced, meaning that if it is used with appropriate care, it is not harmful. In countries where it has been banned, it has not been believed for some time, but in some countries, where the fibre is still used, the subject continues to be publicised. And it continues to hold the fortunes of the asbestos industry.

“AULS 76

The consultant outlined some of the strands on which the Swiss group’s ‘Policy and Strategy’ focused. Rivella called it a “media propaganda offensive” with the aim of protecting the asbestos industry and dampening or stifling the clamour brought about by the growing awareness of the fibre’s danger. “Don’t panic’ is one of the slogans contained in ‘Auls 76’, an operational report, which came out of the Ermatingen seminar, held in November 1976, only five months after Neuss (the meeting called in June by Schmidheiny from which his top executives came out ‘shocked’: ‘his words’ specified the consultant). Auls 76 is a handbook to all intents and purposes, containing precise indications to be followed by managers who are gradually called upon to answer questions posed by workers, trade unions, local administrators, journalists and citizens. It lists a wide range of possible questions and the precise answers and reassurances to be given.

The list of things to which managers must adhere to scrupulously is in seven points.

7 guide lines:

Don’t panic

Try and identify the cause

Learn your lesson

Ask for experts

Try and have a good relationship with the media

Try to reach a friendly agreement

Contact Amiantus’s Tutela del lavoro and Ambiente (Environment and Labour Protection)

15 questions

- Why are you still producing asbestos cement with asbestos in spite it is a know dangerous substance)

- Why have you denied this danger?

- Have your employees been informed on this danger?

- What are you doing to protect your workers?

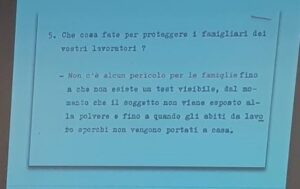

- What are you doing to protect your workers’ families?

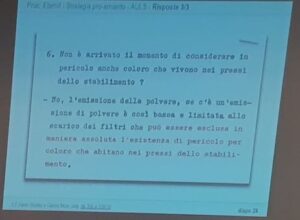

- Isn’t it time to consider those living close to the plant also in danger?

- What about customers and those who work or process asbestos-cement?

- Should you not put warning labels on your products?

- Is it true that asbestos cement roofs become dangerous after abrasions and natural deterioration?

- To what extent are asbestos cement water pipes dangerous for drinking water?

- Ventilation products appear especially dangerous because air conditioning devices circulate and re-circulate asbestos cement dust

- Why are you still using blue asbestos when it is known to be especially dangerous?

- Can’t other fibres be used in the place of the asbestos ones?

- How can your company say there is a safe limit or an acceptable risk? Shouldn’t it be zero?

- Wouldn’t it be just simpler to ban asbestos cement products?

And for each question there is an answer that the manager had to learn by heart because that is the one to be given.

“Auls’ was applied scrupulously and it worked, so much so that in the confidential correspondence between Schmidheiny and CEO Luigi Giannitrapani (letters that are delivered to an exclusive post office box, unrelated to normal mail delivery points), the former congratulates the latter: ‘I’m glad Ausl is bearing fruit’.

Internationally too, the entire asbestos industry was feeling the uncertainty of the future and the weight of the ever-increasing concerns about the risks of disease caused by asbestos. The analysis was careful, not overlooking any detail. The authorities in several states demanded labels with asbestos is harmful to health,” Rivella recalled. “In what language should this be written? A stylised image of a skull and bones would have been a universal symbol”. Never never never would that be accepted , because the skull and bones would have created more apprehension and worry than a sweetened piece of writing. On the subject of writing, the definition ‘asbestos cement product’ was replaced by the preferable ‘fibre cement product’, hiding the word asbestos, because it was the one evoking the risk of cancer.

THE ‘TOUR D’ORIZON

The strategy also included the ‘Tour d’Orizon’, restricted meetings attended by the world’s largest groups under conditions of absolute confidentiality. Rivella said that the meetings with the Americans were strictly oral, so that no trace of them would remain, since legislation in the US was much stricter and more penalising. “Analyses are made of the markets, of the medium- and long-term prospects, of the awareness of the danger and, increasingly present, is the issue of the relationship between asbestos, the environment and health”. That said, the introduction of the Neuss meeting, stated the intention to improve air quality and protect workers from the risks of the fibre. What did Schmidheiny do? “Not much money was spent on security – explained the consultant – for Casale I found less than four billion lire, but indicated in a generic prospectus, in which the various items are listed with roughly rounded figures, without the correspondence of a precise accounting dedicated to security.

TOWARDS CLOSURE

Eternit spa in Italy went into receivership in 1984 and filed for bankruptcy on June 4, 1986. The Ronzone factory was abandoned just as it was: two turns of the key at the gate and a huge concentration of dust that escaped from the cracks and crevices that the weather and time inevitably produced in time.

Schmidheiny was concerned about the competition that would have affected the European market,” the accountant explained, “so he made an offer to the trustee in bankruptcy to sell the Italian Eternit brand and a machine to make slabs to French Eternit, so as not to leave the field open to any competitors (such as the Pesenti).

POST-BANKRUPTCY STRATEGY

The Swiss entrepreneur turned to Guido Bellodi’s Milan-based public relations firm, entrusting it with the task of creating a protective network around his name. “There is a trace of the activity carried out between 1984 and 2005, the year in which all the documentation was seized by the Turin Public Prosecutor’s Office. I don’t know if Bellodi’s activity continued,” said the consultant. According to his documentary reconstruction, Schmidheiny paid Bellodi between one million and one million and 300 thousand Euros for the four-year period between 2001 and 2005. It is not known what was paid between 1984 and 2005, because it was not possible to recover the receipts , as the company changed its name a few times. The Milanese professional drew up a new, more specific manual (referred to in the court documents as the ‘Bellodi Manual’, considered the ‘Bible’ by the promoters and users themselves). It contains precise rules of conduct on how the information should be managed, keeping the focus primarily on Italian Eternit, at most touching on Swiss Becon (in which all Eternit’s pending cases have converged; still active, it is the company that manages the compensation with citizens), but with the utmost care to avoid that the attention touches the top company and, less than ever, the name of Stephan Schmidheiny. Bellodi coordinated monitoring – also with the use of ‘antennas’, among which a free-lance journalist from Casale, who Rivella termed a spy , if we wanted to be more diplomatic, someone who gathered intelligence, above all within the trade union, monitoring the trials, the press, the associations of workers and victims’ families, and arranging transactions to avert the trials as much as possible. On the other hand, there is no mention of the land reclamation, which would have cost ‘much more (‘stellar costs as some witnesses reported in the past). And, in fact, the public bodies that have borne these costs can only confirm this.

The main objective of the public relations campaign was to contain “rumours” at a local level, preventing them from spreading nationally and internationally.

Then, however, the internet came along and, through the computer network, what Pesce called the ‘multinational of asbestos victims’ took shape and strength, facing the ‘multinational of asbestos addicts’. And, as Romana Blasotti Pavesi, the past president of AFEVA, the Association of Families and Victims, warned, “we are more than you are”.

The next hearing will be held on Wednesday the 29th of September when Rivella will be cross examined.

[1] Baron Louis had married an Emsens; he had been accused and convicted in the first instance in the Eternit One maxi-trial, but he died on the eve of the sentence of the appeal trial

Grazie mille Silvana! Ottima e costantemente utilissima sintesi !

Perché non scrivi un libro sintesi di tutti i tuoi precisi e puntuali articoli che ci stai raccontando a futura memoria dei nostri “eroi” defunti a causa di questo terribile male.?

Grazie Silvana. Come sempre puntuale, precisa e preziosa la tua relazione.

Grazie Silvana.