SILVANA MOSSANO

Reportage udienza 22 giugno 2022

Al consulente Andrea D’Anna, professore ordinario di Impianti Chimici all’Università di Napoli Federico II, i difensori di Stephan Schmidheiny hanno chiesto di affrontare tre questioni: 1) valutare quale è stata, sull’ambiente e sulla qualità dell’aria di Casale e dintorni, l’influenza della dispersione di polvere d’amianto proveniente sia dallo stabilimento Eternit sia dalla distribuzione di polverino, feltri e materiale di scarto; 2) valutare quanto hanno influito la polvere d’amianto proveniente sia dai tetti di «eternit» («non sostituiti nonostante l’invecchiamento») sia da altre sorgenti di polvere d’amianto non riferibili alla fabbrica del Ronzone; 3) verificare quale relazione c’è stata tra i luoghi di residenza delle 392 vittime (quelle per cui l’imputato è chiamato a rispondere di omicidio volontario con dolo eventuale) e i luoghi in cui è stata censita la presenza di amianto.

Come ha proceduto l’ingegner D’Anna? Ne ha dato conto nell’udienza di mercoledì 22 giugno in Corte d’Assise a Novara, dove si svolge il processo.

Innanzi tutto, ha individuato le attività produttive del Casalese in cui era utilizzato, o comunque presente, l’amianto: principalmente, ha riassunto l’esperto della difesa, nei settori della refrigerazione, delle costruzioni meccaniche e del cemento. E, in più, non era assente nei comparti dell’abbigliamento, dell’alimentare e del legno. In che modo l’amianto era presente? Intanto, gli stessi capannoni industriali avevano tetti di lastre d’amianto, oppure era impiegato come coibente in certe apparecchiature, o nella realizzazione di particolari pannelli, o in componenti di macchine Linotype.

E, poi, ha completato il consulente, c’era a Casale lo stabilimento Eternit, a partire dal 1907 fino al 1986. Ha anche citato uno stabilimento che produceva manufatti di amianto a Ozzano Monferrato (della Milanese & Azzi, poi Fibronit), ma nel comune monferrino il sindaco e gli storici che hanno ricostruito la storia del paese nei dettagli ricordano sì la presenza di cementifici, ma escludono assolutamente e non trovano traccia documentale dell’attività citata da D’Anna.

Per integrare correttamente il quadro illustrato dall’ingegnere, va però ricordato, sfidando l’ovvietà, che soltanto all’Eternit di Casale, nel quartiere Ronzone, l’amianto fu utilizzato in quantitativi massicci quale materia prima (sia il crisotilo che la crocidolite) per la produzione di lastre e tubi. Negli altri settori no.

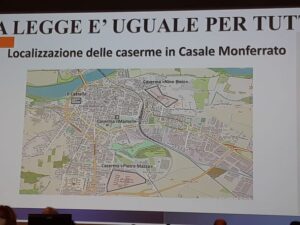

I tetti di «eternit», poi, come ha puntualmente annotato il consulente della difesa, non coprivano soltanto i capannoni di varie fabbriche (Eternit inclusa), ma anche molti altri edifici; ad esempio, ha posto l’accento su quelli militari: il «casermone» a Porta Milano, le «Casermette» al Valentino, la caserma Mameli in via Cavour (centro storico), il Castello che fu sede del Distretto militare e il Poligono di tiro a Ottiglio, paese collinare a poco più di una quindicina di chilometri da Casale.

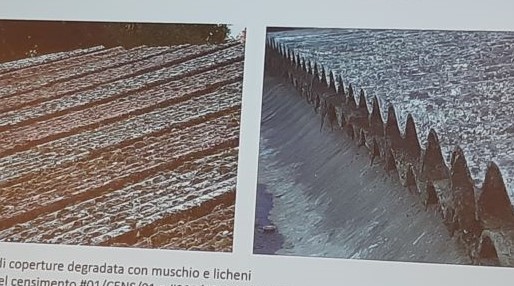

Dai dati dei censimenti effettuati dall’Arpa, il consulente della difesa ha rilevato che, nell’area «Sin (Sito di interesse nazionale per l’amianto) del Casalese», composta da 48 Comuni, furono installati complessivamente 815.114 metri quadrati di coperture, di cui 261.564 nel capoluogo. Il consulente ha affermato che «l’88% di queste coperture furono installare prima del 1976».

Perché sottolineare questa data? Perché è significativo ai fini del processo in corso: si è già più volte detto, ma vale la pena ribadire che fu nel 1976 che l’imprenditore svizzero ereditò dal padre Max il comparto delle fabbriche d’amianto, in Italia e all’estero; prima, era già documentata la sua presenza in azienda, ma ne fu responsabile formalmente dal 1976 fino alla chiusura nel 1986, quando la Eternit stessa chiese il fallimento in Italia (sentenziato dal tribunale a giugno).

Oltre ai tetti – posati su capannoni, edifici pubblici e privati come scuole, ospedale, garage e così via -, altre fonti di diffusione delle fibre di amianto furono, come ha elencato D’Anna, il polverino e gli scarti di produzione, usati ampiamente per coibentare i sottotetti o come «battuto», cioè per rinforzare la pavimentazione di aie, cortili, piazze, strade, sentieri, campetti sportivi e così via. E da dove provenivano il polverino e gli scarti, usati in modo «improprio»? Dallo stabilimento Eternit, ovviamente, ma, ha ribadito l’ingegnere, per lo più prima del 1976.

Ha fornito i numeri, sempre attinti ai censimenti: furono posati 11.285 metri quadrati di polverino nei Comuni del «Sin» (di cui 10.254 nella sola città di Casale) e 28.673 metri quadrati di battuto (di cui 15.926 a Casale).

E tutto questo materiale variamente impiegato – tetti, sottotetti, battuti – è stato purtroppo esposto, come rimarcato dal consulente, al degrado e all’usura, provocati dagli agenti atmosferici, dagli sbalzi termini, da azioni meccaniche come rotture o sfregamento di pneumatici, di camminamenti e così via.

Il professor D’Anna, attraverso l’utilizzo di un codice di calcolo («Calpuff») della dispersione di inquinanti in atmosfera, ha poi individuato, per ciascuna delle macrosorgenti di amianto, il «fattore di emissione media di fibre all’ora». Ecco i risultati calcolati dal consulente nel territorio casalese: per le coperture (cioè tutti i tetti) il fattore di emissione media è stato di 26 miliardi di fibre all’ora; per il polverino nei sottotetti, 540 miliardi di fibre all’ora; per il battuto (in strade, aie, cortili, piazze), 3000 miliardi di fibre all’ora.

Ha calcolato, poi, il fattore di emissione media per lo stabilimento Eternit di via Oggero, risultato pari a 400 miliardi di fibre all’ora, e nell’area ex Piemontese (sempre in via Oggero, dove si frantumavano gli scarti a cielo aperto, passandoci sopra con i cingolati di una ruspa) pari a 230 miliardi di fibre all’ora. In tutto, tra fabbrica e area di frantumazione: 630 miliardi di fibre all’ora, un quinto rispetto a quello dei «battuti» di cortili e campetti su cui giocavano i ragazzini, o delle strade percorse in auto o in bici. E soltanto un po’ di più del fattore di emissione relativo ai tetti di amianto.

La valutazione del professor D’Anna è che, in quanto a dispersione di fibre di amianto, il centro storico di Casale è stato solo marginalmente influenzato dallo stabilimento Eternit, mentre è stato interessato da una notevole concentrazione di fibre aerodisperse proveniente dall’utilizzo di manufatti di «eternit» (cioè, appunto, tetti, vasi, vasche per l’acqua, camini, tubi) o dall’uso improprio degli scarti di lavorazione e del polverino distribuiti principalmente negli anni Cinquanta/Sessanta.

Secondo i suoi calcoli, le emissioni dovute all’usura dei battuti e ai polverini sarebbero state da, circa, 2 a 15 volte maggiori rispetto a quelle causate dalla frantumazione a cielo aperto dei materiali di scarto dell’eternit nell’area ex Piemontese!

Ha detto l’ingegner D’Anna al processo: «I risultati delle simulazioni hanno indicato in maniera inequivocabile che le fibre di amianto derivanti dall’erosione delle coperture, dalla ri-sospensione del polverino in sottotetti aperti e dal battuto in cortili e strade per effetto dell’azione meccanica di sgretolamento hanno contribuito in maniera significativa al deterioramento della qualità dell’aria nel comune di Casale e nei comuni limitrofi». Inoltre, «l’azione delle eventuali emissioni dallo stabilimento era molto bassa a un chilometro dallo stesso». In altre parole, «il contributo dello stabilimento ai fini della concentrazione delle fibre è molto basso già alla distanza di 800 metri».

Il professore ha contestato le conclusioni dei consulenti della procura, Corrado Magnani e Dario Mirabelli, che avevano indicato in dieci chilometri la capacità di dispersione delle fibre in atmosfera. D’Anna ha affermato che la capacità di dispersione delle fibre fino a dieci chilometri indicata dai consulenti della procura «è basata unicamente sulla valutazione epidemiologica del rischio di mesotelioma che, per le persone che avevano abitato entro 10 chilometri dallo stabilimento, risulta superiore rispetto a quello di una popolazione non esposta ad amianto. Secondo il professore partenopeo, i consulenti Magnani e Mirabelli hanno indicato come risultato di dispersione delle fibre la distanza di dieci chilometri «ritenendo che l’unica fonte di emissione di fibre in atmosfera fosse lo stabilimento Eternit».

In realtà, dai risultati dei ripetuti studi eseguiti a Casale da Magnani e Mirabelli era emerso che il rischio per la popolazione era massimo per chi aveva vissuto in prossimità dello stabilimento e diminuiva progressivamente all’aumentare della distanza, pur restando ancora più alto del valore di fondo (cioè confrontato con la popolazione piemontese non esposta) fino ad una distanza di 10 chilometri dall’Eternit. Questo dato è comprovato e pubblicato su autorevoli riviste scientifiche. Risulterebbe, pertanto, incompatibile con l’affermazione che il rischio sia stato generato da sorgenti numerose e diffuse.

E invece D’Anna insiste che c’erano appunto anche i tetti (soprattutto se degradati), il polverino nei sottotetti e i «battuti», di gran lunga più famigerati – secondo i calcoli da lui esposti – dello stabilimento Eternit e dell’area ex Piemontese messi insieme.

DOVE VIVEVANO LE VITTIME

Proprio tenendo conto delle varie sorgenti di emissione delle fibre – stabilimento Eternit, altre aziende del Casalese, edifici con tetti di amianto, sottotetti con polverino e battuti vari – il consulente ha anche svolto un lavoro capillare raffrontando i 392 casi, cioè i lavoratori e residenti morti per l’amianto elencati nel capo di imputazione, con la vicinanza a qualcuna di queste sorgenti, per valutare, a suo parere, quale possa essere stata per ciascuno di loro la fonte più attendibile di dispersione, inalazione, malattia e morte.

Ha concluso che «55 lavoratori su 62 hanno avuto almeno un periodo di residenza a meno di 300 metri da un luogo in cui è stato usato in modo improprio il polverino come battuto o a meno di 50 metri da un sottotetto con polverino». E ancora: «312 residenti su 330 hanno abitato, almeno in un periodo della loro vita, a meno di 300 metri dove c’era un “battuto” e a meno di 50 metri dove poi è stato trovato un sottotetto con polverino».

Laddove è più difficile riscontrare queste concomitanze, il professor D’Anna afferma che queste persone sono comunque vissute a più di 300 metri da siti in cui comunque ci sono stati utilizzi impropri di amianto, o hanno abitato in case dove c’era amianto anche se non risulta dal censimento, o hanno abitato in zone non distanti da caserme e installazioni militari.

In sintesi, il consulente della difesa ritiene che lo stabilimento del Ronzone e l’area ex Piemontese della frantumazione non sono state le sole sorgenti della dispersione di fibre di amianto, perché non di meno o, addirittura, ben di più hanno infettato l’aria casalese i molti tetti di «eternit» che non sono stati sostituiti quando erano ammalorati e i vari «usi impropri»: cioè, ripetiamo, sottotetti e battuti con polverino, fornito inequivocabilmente dalla fabbrica Eternit, ma quasi tutto «prima del 1976», secondo il professore. Una certezza, quest’ultima, che il consulente dovrebbe aver appurato su solida documentazione che dimostri che, dopo quell’anni, scarti e polverino non uscirono più dalla fabbrica.

E I CAMION PER LA CITTA’?

Alla visione di insieme ricostruita da D’Anna manca PERò qualche dato; ad esempio, non sono stati ricordati, come sorgenti di diffusione di fibre, i Magazzini Eternit di piazza d’Armi, lo scalo ferroviario «Piccola Velocità» dove arrivava la materia prima, il viavai continuo per decenni (anche tra il 1976 e il 1986) dei camion senza teloni di copertura che trasportavano sia i sacchi di amianto in andata sia i manufatti finiti in ritorno tra lo stabilimento del Ronzone e i magazzini di piazza D’Armi.

IL RIMPROVERO SUI TETTI AMMALORATI

Infine, D’Anna ha più volte rinnovato, nel corso della sua relazione, una sorta di rimprovero implicito nei confronti dei casalesi – amministratori pubblici e cittadini – che non si sono curati di sostituire per tempo tetti ammalorati o di rimuovere scarti, battuti o polverini diffusi. Ha ben ragione il professore, sì, ha ben ragione. Se solo i casalesi avessero saputo quello che i produttori di amianto già sapevano sulla cancerogenicità dell’amianto e che, con diffusa propaganda, hanno tenuto nascosto o minimizzato per decenni!

L’IDONEA DISCARICA

A Casale c’è, dal 2001, un impianto specifico per lo smaltimento dei manufatti di amianto dismessi e la sua costruzione non è stata mai osteggiata dalla popolazione, proprio perché consapevole dell’importanza di avere una discarica idonea per favorire e accelerare le bonifiche. (In realtà, le bonifiche sono iniziate ben prima e i manufatti dismessi venivano conferiti in discariche esterne). E si è andati molto avanti su questo fronte, appena si è capita la gravità e appena si è potuto: il territorio di Casale è quello che è stato bonificato di più. Forse di più al mondo.

E LO STABILIMENTO ABBANDONATO?

Si è anche bonificato, con un dispendio enorme della collettività, lo stabilimento al Ronzone (e pure l’area ex Piemontese) che, nel 1986, fu abbandonato dalla società Eternit, incurante dell’inevitabile degrado che, come ha appunto spiegato lo stesso consulente della difesa, avrebbero provocato intemperie, pioggia, ghiaccio, vento, finestre rotte, tetti (d’amianto) crollati, sacchi (contenenti amianto) esposti a tiri d’aria incrociati.

Nel maxiprocesso Eternit, già celebrato a suo tempo a Torino, fu domandato a tutti i sindaci e presidenti regionali chiamati a testimoniare se l’imputato Schmidheiny o qualcuno a lui collegato si fosse fatto vivo, negli anni, per offrire un contributo alla bonifica. La risposta di tutti fu: «No, mai».

La spiegazione a discolpa è nota: l’Eternit era fallita e, quindi, della bonifica avrebbero dovuto farsene carico gli organismi della procedura fallimentare.

E’ la logica del «non mi compete», utilizzata come giustificazione in ambito giudiziario che attiene all’imputato; altro è la condotta etica e di coscienza che attiene all’uomo.

E’ che, purtroppo, il conto doloroso lo stanno pagando incolpevoli e sventurati uomini e donne di Casale e dintorni, tra cui i 392 uomini e donne indicati nel processo e che sono soltanto una parte, poca parte del numero totale. Anche in altre città le coperture di amianto erano altrettanto diffuse su capannoni ed edifici vari, anche in altre città queste coperture si sono deteriorate (e poco sono state bonificate), anche in altre città c’erano attività produttive della refrigerazione, delle costruzioni meccaniche, dell’abbigliamento eccetera che, in qualche misura, usavano strumenti e coibentazioni con presenza di amianto, ma torniamo a insistere: altrove – dove non c’erano fabbriche di manufatti di amianto – non ci sono stati tanti morti come a Casale e dintorni. Perché?

PROSSIMA UDIENZA

E’ fissata per l’11 luglio: sarà ascoltato, in esame e controesame, il professor Gary Marsh, docente dell’Università di Pittsburgh.

Translation by Vicky Franzinetti

By

Silvana Mossano

The Defense: “More asbestos fibers from worn roofs and dust than from Eternit and crushing area”

Expert witness Prof. Andrea D’Anna, a lecturer in Chemical Systems at the Federico II University of Naples (and not, as mistakenly reported previously, Occupational Medicine Specialist Dr Maurizio Danna), was asked by Stephan Schmidheiny’s defense attorneys to answer three questions:

- to assess what influence the dispersion of asbestos dust from both the Eternit plant and the spread of dust, felts and waste had on the environment and air quality in and around Casale;

- to assess the extent to which asbestos dust from both the Eternit roof-tops (“not replaced despite aging”) and other sources of asbestos dust not referable to the Ronzone factory impacted on the people’s health; and

- to ascertain the relationship between the places of residence of the 392 victims (those for which the defendant is charged with murder with possible intent or willfulness) and the places where asbestos was surveyed.

How did the engineer D’Anna proceed on Wednesday, June 22, in the Assize Court in Novara, where the trial is being held

First, he identified all the manufacturing activities in the Casalese area where asbestos was used, or otherwise present: mainly, the defense expert summarized, in the fridge [?] manufacturing, mechanical construction and cement. And, in addition, it was present in small quantities in the clothing, food and wood industries. Meanwhile, the industrial warehouses themselves had asbestos sheet roofs, or it was used as an insulator in certain equipment, or in the making of particular panels, or in Linotype machine components.

The expert then concluded there was also an Eternit plant in Casale, starting in 1907 until 1986. He also mentioned a plant that manufactured asbestos products in Ozzano Monferrato (by Milanese & Azzi, later Fibronit). However, in the Monferrato Municipality the Mayor and historians who have studied the history of the town in detail confirm the presence of cement factories, but they firmly exclude and find no documentary evidence of the asbestos related activity quoted by D’Anna.

To complete the picture illustrated by the engineer, however, one should not forget that only at Eternit in Casale, in the Ronzone district, was asbestos used in massive quantities as a raw material (both chrysotile and crocidolite) for the production of sheets and pipes. In other areas it was not.

“Eternit” roofs, then, as the defense counsel pointedly noted, covered not only the warehouses of various plants (Eternit included), but also many other buildings; for example, the expert listed military barracks: the “Casermone (the big barrack)” at Porta Milano, the “Casermette (the Little Barracks)” at Valentino, the Mameli barracks on Via Cavour (town center), the Castle that was the headquarters of the Military District, and the Shooting Range at Ottiglio, a hillside town just over fifteen kilometers from Casale.

Census data by Arpa (the Region’s Environmental Agency) the defense consultant indicates that a total of 815,114 square meters of roofing was installed in the Sin (Site of National Interest for Asbestos) area of Casalese,” consisting of 48 municipalities, of which 261,564 were in Casale itself. The expert stated that “88 percent of these roofs were installed before 1976.”

Why emphasize the date? Because it is meaningful for the purposes of the current trial: it has already been mentioned several times, but it is worth reiterating that it was in 1976 that the Swiss entrepreneur inherited the asbestos factories sector, in Italy and abroad from his father Max; before that, it is documented that he was in the company, but he became formally responsible for it from 1976 until its closure in 1986, when Eternit filed for bankruptcy in Italy (ruled by the court in June).

D’Anna listed in addition to roofs – on warehouses, public and private buildings such as schools, hospitals, garages and so on – other sources of spreading asbestos fibers were, dust and production waste, used extensively to insulate attics or to strengthen paving in farmyards, courtyards, squares, roads, paths, sports fields and so on. And where did the dust and waste, used “improperly,” come from? From the Eternit plant, of course, as the engineer reiterated, mostly before 1976.

He provided the numbers, again drawn from censuses: 11,285 square meters of dust were laid in the “Sin” municipalities (including 10,254 in the city of Casale alone) and 28,673 square meters of paving (including 15,926 in Casale). All this material- used for roofs, attics, and paving -was unfortunately exposed to wear and tear, caused by weathering, sudden temperature changes, mechanical actions such as breaking or rubbing of tires, used as paths for walking and so on.

Professor D’Anna, used the Calpuff calculation system of the dispersion of pollutants into the atmosphere, then identified, for each of the macrosources of asbestos, the “average fiber emission factor per hour.” Here are the results calculated by the consultant in the Casale area: for roofing (i.e., all roofs), the average emission factor was 26 billion fibers per hour; for dust in attics, 540 billion fibers per hour; for paving (in streets, yards, courtyards, squares), 3000 billion fibers per hour. He then calculated the average emission factor for the Eternit factory in Via Oggero, which was found to be 400 billion fibers per hour, and in the former Piemontese area (also in Via Oggero, where open-air waste was crushed by passing over it with bulldozer crawlers) 230 billion fibers per hour. In all, between factory and crushing area: 630 billion fibers per hour, one-fifth that of the yard and playground paving on which kids played, or the roads traveled by car or bicycle. Only slightly more than the emission factor related to asbestos roofs.

Professor D’Anna’s assessment is that, in terms of asbestos fiber dispersion, the town center of Casale was only marginally affected by the Eternit plant, while it was affected by a significant concentration of airborne fibers from the use of “eternit” artifacts (i.e., precisely, roofs, pots, water tanks, chimneys, pipes) or from the misuse of processing waste and dust distributed mainly in the 1950s/60s.

According to his calculations, the emissions from the wear and tear of the paving and dusting would have been from, about, 2 to 15 times greater than those caused by the open-air crushing of asbestos waste materials in the former Piedmont area! He stated the trial, “The results of the simulations unequivocally indicated that asbestos fibers resulting from erosion of roofing, re-suspension of dust in open attics, and paving in courtyards and streets by the mechanical crushing contributed significantly to the deterioration of air quality in the municipality of Casale and neighboring municipalities.” In addition, “the action of any emissions from the plant was very low at one kilometer from the plant.” In other words, “the plant’s contribution to fiber concentration was very low already at the distance of 800 meters.” The professor challenged the conclusions of the prosecutor’s consultants, Drs Corrado Magnani and Dario Mirabelli, who had indicated ten kilometers as the dispersion capacity of the fibers into the atmosphere. D’Anna said that the fiber dispersion capacity of up to ten kilometers indicated by the prosecutor’s consultants “is based solely on the epidemiological assessment of the risk of mesothelioma, which, for people who had lived within 10 kilometers of the plant, is higher than for a population not exposed to asbestos. According to the Neapolitan professor, consultants Magnani and Mirabelli indicated as a result of fiber dispersion the distance of ten kilometers “believing that the only source of fiber emission into the atmosphere was the Eternit plant.” In fact, the results of the repeated studies carried out in Casale by Magnani and Mirabelli had shown that the risk to the population was highest for those who had lived near the plant and decreased progressively as the distance increased, although it still remained higher than the background value (i.e., compared with the unexposed population of Piedmont) up to a distance of 10 kilometers from Eternit. This finding is substantiated and published in authoritative scientific journals. It would, therefore, result incompatible with the claim that the risk was generated by numerous and widespread sources.

However, D’Anna insists that there were precisely also the roofs (especially when old), the dust in the attics and the “pavings,” by far more infamous – according to the calculations he set forth – than the Eternit plant and the former Piedmont area combined.

WHERE DID THE VICTIMS LIVE?

By taking into account the various sources of fiber emissions – the Eternit plant, other companies in the Casalese area, buildings with asbestos roofs, attics with dust and various beatings – the consultant also did extensive work comparing the 392 cases, i.e., workers and residents who died from asbestos listed in the indictment, with their proximity to any of these sources, to assess, in Dr D’Anna’s opinion, what the most reliable source of dispersion, inhalation, illness and death may have been for each of them. He concluded that “55 out of 62 workers had at least one period of residence within 300 meters of a place where dust was misused as paving or within 50 meters of an attic with dust.” And again, “312 out of 330 residents have lived, at least at some time in their lives, within 300 meters where there was improper use of asbestos and within 50 meters where an attic with dust was later found.”

Where it is more difficult to find these measurements, Professor D’Anna says that these people nevertheless lived more than 300 meters from sites where asbestos was inappropriately used, or lived in houses where there was asbestos even though it does not show up in the census, or lived in areas not far from barracks and military installations.

In summary, the defense expert believes that the Ronzone plant and the former Piedmontese crushing area were not the only sources of the dispersion of asbestos fibers, because airborne fibers in Casale were mainly caused by the many “eternit” roofs that were not replaced when they were broken and the various “improper uses,” that is, we repeat, attics and paving with powder, supplied by the Eternit factory, but almost all of it “before 1976,” according to the professor. A certainty, that the expert should have carefully documented showing that, after those years, waste and dust were no longer from the Eternit plant.

AND THE LORRIES DRIVING AROUND TOWN?

D’Anna’s list lacks some data; for example, the Eternit Warehouses in Piazza d’Armi, the “Piccola Velocità” railway yard where the raw material arrived, the continuous coming and going for decades (even between 1976 and 1986) of lorries without tarpaulins that transported both bags of asbestos on the outward journey and finished artifacts on the return journey between the Ronzone plant and the warehouses in Piazza D’Armi were not mentioned as sources of the spread of fibers.

REPROACH ON THE BROKEN ROOF-TOPS

Finally, throughout his report D’Anna repeatedly (& implicitly) reproached the Municipality of Casale and the District – Local Authorities and communities- who did not replace deteriorated roofs in time or remove widespread waste, paving or dust. The professor is quite right, yes, he is quite right. If only the people of Casale had known what the asbestos manufacturers already knew about the carcinogenicity of asbestos and which, with widespread propaganda, they kept hidden or downplayed for decades!

A SUITABLE LANDFILL

Since 2001, Casale has had a specific facility for the disposal of decommissioned asbestos artifacts, and its construction was never opposed by the population, precisely because they were aware of the importance of having a suitable landfill to facilitate and accelerate remediation and decontamination. In fact, remediation began well before that, and at the time the decommissioned artifacts were being delivered to external landfills.) The seriousness of the matter was understood and as soon as it was possible the Las acted: the Casale area has mostly been decontaminated. Perhaps the best clean up in the world.

WHAT ABOUT THE ABANDONED PLANT?

The community decontaminated the plant at Ronzone and in the former Piemontese area was abandoned by the Eternit company in 1986, at great cost. The Eternit Company appears to have been indifferent to the inevitable degradation that, as the defense expert himself explained, would have been caused by bad weather, rain, ice, wind, broken windows, collapsed (asbestos) roofs, sacks (containing asbestos) exposed to cross-winds.

In the Eternit maxi-trial, already held at the time in Turin, all the mayors and regional presidents (Governors) called to testify were asked if the defendant Schmidheiny or someone connected to him had come forward over the years to offer a contribution to the cleanup. Everyone’s answer was, “No, never.” The defense’s excuse is well known: Eternit was bankrupt and, therefore, the cleanup should have been taken care of by the bankruptcy proceedings.

It follows the logic of “it is not my responsibility,” used as justification in the judicial sphere by the defendant; the ethical conduct and conscience will fall to the man. Unfortunately, the painful bill is being paid by blameless and unknowing men and women in and around Casale, including the 392 men and women named in the trial and who are only a part, a small part of the total number. In other cities too, asbestos roofing was just as prevalent on warehouses and various buildings, in other cities too these roofs deteriorated (and there was a limited clean- up), in other cities too there were manufacturing of fridges, mechanical construction, clothing, etc. that, to some extent, used tools and insulation with asbestos, but let us go back and insist: elsewhere-where there were no factories of asbestos artifacts-there were not as many deaths as in Casale and its surroundings. Why?

NEXT HEARING

It is set for July 11: Professor Gary Marsh, from the University of Pittsburgh, will be heard in direct and cross.

Bellissimo ma tristissimo reso conto. Più il processo continua più le “carte” sembrano ingambugliarsi. Ci vuole proprio l’Avvocato

“azzeccagarbugli” per uscirne auguriamoci con giusta e equa sentenza. Grazie Silvana . Paolo

Tante grazie Silvana!

Le contraddizioni e omissioni,

anche molto clamorose, rilevate dalla relazione del prof. consulente della difesa, sarebbero forse un po meno se i consulenti ( tutti ) fossero sottoposti per legge a giurare e rispondere di eventuali falsi e/o condotte risalenti a conflitti d’interesse … , e a dichiarare l’entità dei compensi ricevuti per tali prestazioni attuali e pregresse…

Ancora un grande grazie Silva e alla prossima.

Terribile come possa essere distorta la realtà inoppugnabile dei fatti!

Grazie per le ultime informazioni. Per i casalesi è importante avere una voce che con chiarezza espone i fatti e li rende più comprensibili.