SILVANA MOSSANO

Reportage processo Eternit Bis, udienza 20 settembre 2021

Alcuni anni fa, era stato bandito il concorso dal Comune di Casale per assegnare un incarico a tempo indeterminato nel settore tecnico. Un candidato che, con il punteggio acquisito, era stato inserito nella parte alta della graduatoria, alla fine non accettò: rinunciò al posto fisso e sicuro, per paura di trasferirsi nella città dell’amianto. Che, poi, non finiremo mai di dirlo: Casale Monferrato non è la città dell’amianto, caso mai è la città che ha lottato e ha reagito contro l’amianto; lo ha fatto per sé e per tutte quelle altre città che, nel mondo, si sono trovate intossicate, ingiustamente e inconsapevolmente, dalla fibra cancerogena.

Si insite a dire che, ora, non c’è nessun luogo al mondo dove si è sviluppata una così radicata sensibilità nei confronti della fibra e dove si sono fatte più bonifiche che in ogni dove: il timore, però, non è ancora sradicato.

L’episodio è emerso all’udienza di venerdì 20 settembre del processo Eternit Bis, che si svolge in Corte d’Assise (presieduta da Gianfranco Pezone, affiancato da Manuela Massino e dai giudici popolari), nei confronti dell’imputato Stephan Schmidheiny, accusato di aver causato (omicidio volontario con dolo eventuale) la morte per amianto di 392 casalesi. E’ dell’amianto impiegato nella produzione di lastre e tubi allo stabilimento Eternit – affacciato su via Oggero al Ronzone e che l’imprenditore svizzero ha gestito direttamente dal 1976 al 1986 – che si discute.

«Il programma di bonifica a Casale è iniziato nel 1997, con l’arrivo dei primi fondi dedicati» ha esordito l’architetto Piercarla Coggiola, che fin da allora se n’è occupata direttamente e dal 2010 è dirigente dell’Ufficio Ambiente Ecologia. Tra l’altro, il sindaco Federico Riboldi, anche lui teste al processo, ha sottolineato che «è una peculiarità di Casale la creazione di una autonoma Direzione Ambiente votata prioritariamente all’attività di bonifica, che è invece assente in Comuni di media grandezza paragonabili al nostro».

L’architetto Coggiola ha raccontato, con rigoroso puntiglio e precisione, e soprattutto con la preparazione di chi, giorno per giorno, vive e sperimenta sul campo, le fasi storiche di cui è stato punteggiato il percorso di liberazione dall’amianto. «Amianto free» è l’anelito della collettività casalese. E ci si sta arrivando.

Quindi, nel 1997 si avvia il piano di bonifica, «ma, già in precedenza, l’amministrazione aveva acquisito, con soldi propri, gli ex Magazzini Eternit di piazza d’Armi, bonificati e poi trasformati in multisala cinematografica e polo espositivo».

Inoltre, dal curatore fallimentare, e con il benestare del giudice delegato, il Comune aveva acquisito il corpo principale dell’ex stabilimento produttivo di via Oggero (abbandonato nel 1986) e l’area cosiddetta «Ex Piemontese».

«Già nel 1994 – ha documentato l’architetto Coggiola – era stato messo a punto il cosiddetto Piano Urban, per partecipare a un bando europeo con l’obbiettivo di ottenere fondi da destinare a bonifiche, monitoraggi dell’aria e realizzazione della discarica dedicata all’amianto. Purtroppo, però, non era passato». Lavoro inutile? Niente affatto: «Era stato utilizzato, successivamente, per ottenere fondi dal cosiddetto Piano Seveso, appunto nel 1997». Fu definito un perimetro di 48 Comuni, corrispondente all’area sanitaria dell’ex Ussl 76, con Casale Capofila (nel 2000 divenuto «Sin», cioè Sito di interesse nazionale), esteso su una superficie di 740 chilometri quadrati.

«Complessivamente, in tutti questi anni, sono stati assegnati, per diversificati interventi di bonifica, 120 milioni di euro, di cui 64 ottenuti dallo Stato nel 2015» dopo la delusione della sentenza di Cassazione del maxiprocesso Eternit Uno.

Lo stabilimento

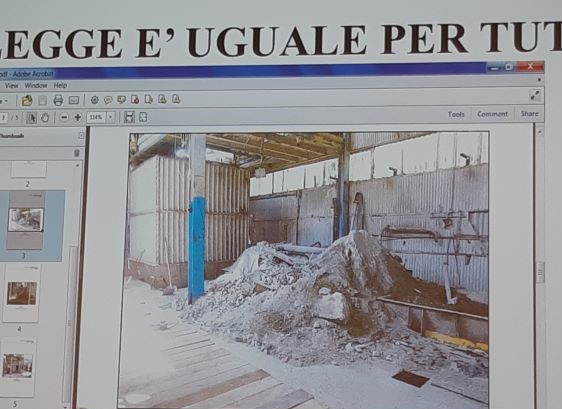

Il Comune lo acquistò nel 1995 e, immediatamente, attivò la commissione di studio per predisporre la bonifica. A ottobre ’97, appena giunse notizia dell’assegnazione dei fondi, fu approvato il progetto esecutivo, fu avviata la gara d’appalto, ma l’assegnazione si inceppò perché la ditta Decam, seconda classificata, fece ricorso al Tar e poi al Consiglio di Stato. Alla fine vinse, ma si trovò subito in difficoltà; così «Arpa e Asl divisero l’area in diversi settori, per ciascuno dei quali fu approntato un piano specifico e si procedette per tranches». Da lì in poi filò tutto liscio? No, perché si trovò più amianto di quello previsto che fece lievitare le pratiche e slittare i tempi. Fino a che la fabbrica, bonificata e demolita, fu sepolta sotto una colata di calcestruzzo che i casalesi chiamarono la «spianata». «Costo complessivo dell’intervento: 7 milioni di euro, sommando i 5,9 milioni della bonifica versati a Decam (incluse le spese di contenzioso e la ricopertura successiva con terra) e un milione e centomila euro per la bonifica sostenuta durante i lavori del Parco».

Parco «Eternot»

Sopra la spianata, è stato realizzato il Parco Eternot (cioè No eternit) – costo: 3 milioni di euro – inaugurato il 10 settembre 2016, «un’opera molto importante per la comunità casalese – ha sottolineato la teste – tanto che, a ogni ricorrenza, si festeggia il compleanno di questo luogo simbolo».

Percorso accidentato anche in questo caso ostacolato da contenziosi con la Coutenza dei Canali Lanza e Mellana, da rilevata presenza di amianto nella fanghiglia sul fondo e sulle pareti del Lanza (si è bonificato il 1° lotto, a ottobre, in asciutta, si procede al secondo, e in autunno 2022 si concluderà con il terzo) e dal ritrovamento di rottami e polverino in alcuni capannoni che il fallimento Eternit aveva ceduto a privati (e che li avevano bonificati in modo molto approssimativo).

Palazzina ex uffici

Quando il Comune, con la ferma determinazione dell’allora giunta di Riccardo Coppo (pronta a cambiare destinazione d’uso del sedime se non si fosse trovato un accordo), comprò dal curatore del fallimento Eternit lo stabilimento con la precisa intenzione di bonificarlo a regola d’arte come si stimava che un privato difficilmente avrebbe fatto, rimase esclusa dal blocco la palazzina degli uffici, assegnata a un altro creditore, che poi fallì. Nuovo inciampo. Passarono anni e amministrazioni, fino a che si riuscì a sbloccare l’impasse e il Comune l’acquisì per 63 mila euro, mettendola in sicurezza. «Trovammo tanta polvere lì dentro, ovunque, persino su una scrivania, su fogli di carta e penne abbandonate» ha ricordato l’architetto Coggiola. Rimangono ancora alcune verifiche da completare, prima di destinare l’edificio, con gli opportuni interventi di ristrutturazione e adattamento, a centro polivalente per attività museali, giovanili, didattiche.

La dirigente ha anche ragguagliato sul grave inquinamento individuato nell’area dell’Ex Piemontese, dove avveniva la frantumazione degli scarti. Una parte è stata liberata dall’amianto e vi è sorto l’asilo Verdeblu. Un altro polo, più distante, deve ancora essere bonificato.

La «spiaggetta»

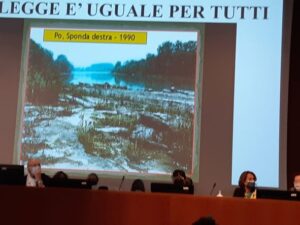

«Era una vera e propria spiaggia generata dai reflui espulsi nel canale di scarico dell’Eternit, che finiva in Po, sulla sponda destra» ha spiegato la testimone. «Era una delle zone più pericolose, molto esposta ed estesa: 6500 metri quadri per una profondità di 5 metri. Il progetto di bonifica è cominciato nel 1998 e completato nel 2000. «Non potevamo portare via tutto il materiale, così è stato realizzato un sarcofago con una tecnica innovativa basata su iniezioni di calcestruzzo liquido nel terreno». Coggiola ha ricordato che «pochissimo dopo l’ultimazione dell’intervento, a ottobre 2000 arrivò l’alluvione; beh, è stata una sorta di collaudo: l’opera ha tenuto». Dopo, è stata rinaturalizzata e non si vede più la differenza con il resto del paesaggio.

Discarica Bagna

«Pensavamo a quest’area lungo il greto del Po, sponda sinistra, come a un sito inquinato per lo sversamento di diversi tipi di rifiuti chimici e, come tale, pensavamo di trattarlo. Ma, dopo l’alluvione del 2000, quando si fecero gli scavi per l’allungamento del ponte sul Po, nella discarica Bagna venne fuori anche l’amianto» ha spiegato la dirigente. E si è dovuto bonificare pure quello.

Baracche sul fiume

Sono le costruzioni realizzate nei decenni come luoghi ricreativi integrati nell’ambiente fluviale. Ma per costruirle furono impiegati molti pezzi d’eternit. «Stiamo monitorando le baracche, cercando di individuarne i proprietari o capire se sono abbandonate». Una, in particolare, la cosiddetta «baracca di Radames» dal nome del suo proprietario, ha reso necessario un intervento piuttosto impegnativo: «Fatiscente, con pareti di eternit e pure polverino nel basamento. E’ stata bonificata, demolita e, al suo posto, si è realizzato un piccolo belvedere rialzato con suggestiva visione verso il Po».

I tetti di «eternit»

Nel corso di oltre due decenni sono stati eseguiti censimenti a tappeto. Le coperture d’amianto negli edifici pubblici dei 48 Comuni del «Sin» sono state praticamente quasi tutte rimosse e sostituite. Esempi: ex Magazzini Eternit, scuole, Mercato ortofrutticolo (che di recente, tra l’altro, è stato abbattuto), Biblioteca, tribuna dello stadio Natal Palli, ospedale Santo Spirito, poliambulatorio in via Palestro, casermone e altri nei paesi.

Anche molti cittadini privati, incentivati dai contributi messi a disposizione per la rimozione e, con la forza di una capillare e massiccia campagna di sensibilizzazione (non estranea alla vastità del dramma sanitario), hanno bonificato case, rimesse, capannoni e piccole superfici come pollai e casotte. «Si possono ancora fare richieste di contributi – ha spiegato la dirigente –: bonificheremo l’amianto finché ce n’è».

Il polverino

Questo è il più dannato. Scarto di produzione che è stato trovato nei luoghi più disparati: nella piazza di Ticineto («dove è stato sperimentato un metodo “bagnato” che abbiamo dovuto inventare qui»), nei vialetti del cimitero dello stesso paese, all’ex palazzo Cova Adaglio ora Media Trevigi, nel cortile del castello Paleologo, nel sagrato della chiesa di Odalengo Grande, in campi di bocce, cortili di condomini, sottofondi di piazze e strade private, nel cotile della casa di riposo e in quello dell’Istituto superiore Leardi (di quest’ultimo si è fatta carico la Provincia).

Discarica dedicata

«Il Comune di Casale ha rinunciato a vendere lotti appetibili (praticamente per un valore di un milione e 400 mila euro) nella zona industriale di strada Valenza per destinarli alla realizzazione di una discarica specifica per l’amianto, con vasche diversificate per lastre dismesse e polverino. La discarica, realizzata a partire dal 2001, è gestita direttamente dall’ente pubblico: è un caso raro, solitamente se ne occupano società private» ha spiegato l’architetto Coggiola, che è la referente tecnica dell’impianto: «Uno strumento fondamentale – ha puntualizzato – che ha consentito di svolgere, velocizzare, incentivare e contenere i costi delle bonifiche di amianto». All’Arpa regionale è demandato il compito di eseguire costanti ispezioni a sorpresa, per monitorare la correttezza della gestione.

IL SINDACO RIBOLDI

L’anno in cui Federico Riboldi, sindaco di Casale dal 2019, nasceva, cioè il 1986, veniva chiusa, anzi abbandonata dopo il fallimento richiesto dalla stessa società, la fabbrica Eternit, dopo 80 anni di attività.

Proseguendo nel solco delle amministrazioni che l’hanno preceduta, la giunta Riboldi si trova ancora oggi ad affrontare le conseguenze di quella attività industriale. Il sindaco ne ha dato testimonianza all’udienza in Assise di venerdì 20 settembre, evidenziando «il grande sforzo della collettività di Casale e delle amministrazioni che si sono avvicendate, rendendo questa città un simbolo nel mondo e un esempio per le bonifiche d’amianto».

Il pm Gianfranco Colace ha chiesto conto al sindaco dei costi che la comunità si è trovata a sostenere.

«Il primo grande prezzo, incalcolabile, è senza dubbio quello delle vittime, con la scia di dolore immenso e una popolazione impoverita».

Riboldi ha poi richiamato le spese sostenute anche con risorse attinte dai bilanci comunali, «sia per acquisizioni sia per contenziosi legali» oltre che per la rinuncia a incassare congrue somme dalla vendita di lotti industriali che si è invece scelto di destinare alla realizzazione della discarica per l’amianto.

Riboldi si è pure soffermato molto sul «danno di immagine causato dall’amianto con ricadute fortemente negative che hanno bloccato alcune fasi importanti dello sviluppo, hanno scoraggiato insediamenti di imprese e di nuove famiglie a causa dei timori generati dall’inquinamento d’amianto, hanno inciso sulle attività scolastiche e sportive e, molto, sull’attrazione turistica».

Il sindaco ha altresì poi fatto presente come le pratiche amministrative di vario tipo a sostegno delle bonifiche hanno rallentato l’attività della macchina comunale in più settori.

«La cosa più terrificante – ha insistito – è il fatto di aver abbandonato una bomba ecologica di questo tipo vicino alle case, alle scuole, in mezzo alla gente».

E Schmidheiny, o qualcuno legato a società del suo gruppo, si è mai offerto di contribuire alle bonifiche?, si è informato il pubblico ministero Colace. «Che io sappia no».

Però, un abboccamento un po’ inconsueto c’è stato, «a novembre 2017, quando ero vicepresidente della Provincia. Il rappresentante di un’impresa nel settore sanitario, sapendo che sono di Casale, mi avvicinò proponendomi un lavoro non meglio precisato sull’immagine del territorio di Casale». E come andò? «Ne parlai informalmente con la dottoressa Daniela Degiovanni e lei mi suggerì di dire a questa persona che, prima di avviare qualsiasi discorso, mettesse per iscritto che non aveva nessun legame con Schmidheiny o l’Eternit. Seguii il consiglio e gli mandai un whatsapp». E allora? «Non si fece più vivo».

LA FIGLIA DELLA PANETTIERA

«A mia mamma fu diagnosticato il mesotelioma a novembre 2001. E lei subito: “Non c’è niente da dire, tanto sappiamo tutto”».

La figlia Giovanna Patrucco che, al Ronzone, è vissuta, al civico 61 di via Oggero (e ancora ci abita a pochi numeri di distanza), laureata in Chimica, dirigente prima all’Ospedale Mauriziano di Torino poi al Sant’Andrea di Vercelli, ha raccontato il quartiere dell’Eternit nei decenni in cui i genitori gestivano la bottega di commestibili poco distante dalla fabbrica. «Noi si abitava nel retrobottega, a quell’epoca, per chi aveva un negozio alimentare, era così. Molte operaie e operai erano nostri clienti: pane, formaggio, salame, prosciutto. Li conoscevamo bene per nome e si instaurava una certa confidenza».

Sua madre, molto scrupolosa nel cercare di preservare gli alimenti, specialmente le pagnotte esposte in cestoni, usava uno scopino per picchiettare sulle tute dei clienti tirando via un po’ di polvere prima di farli entrare in bottega.

«La polvere – ha spiegato incalzata dalle domande del pm Mariagiovanna Compare – era la porta d’ingresso del Ronzone. Si trovava ovunque. Quando si è dovuto riverniciare le persiane, mia mamma ha detto “facciamole grigie, così non si vede la polvere!”».

La memoria della testimone è vivida: «Ricordo tutto. I cortili erano coperti di polvere, e così i marciapiedi, e le stecche delle persiane; le strade ne erano sepolte, la polvere nascondeva addirittura i binari del “tramvajin” e i miei genitori si raccomandavano che stessi attenta quando andavo in bicicletta per non finirci dentro, ai binari».

Le scarpe, poi, «che rabbia arrivare a scuola che erano tutte impolverate!».

E l’area ex Piemontese? «Lì si frantumavano gli scarti e salivano su delle nuvole. Gli scarti li usavano in molti; a casa mia, per esempio, delimitavano l’aiuola. Invece, il cortile del vicino, Bruno Besso, poi morto di mesotelioma, era stato livellato col polverino».

Poi c’era la «spiaggetta»: «Oh, sì, da piccoli andavamo a fare il bagno, da ragazzine a prendere il sole. E la domenica si facevano le grigliate. Per noi era una piccola riviera».

Polvere, polvere e manifesti da morto. «In casa mia si percepiva che qualcosa non andava; c’era una sensazione di allerta».

Così, la diagnosi di mesotelioma fu uno choc, ma non proprio una sorpresa… «tanto sappiamo tutto…».

«Mia madre era consapevole di quel che l’attendeva e volle firmare personalmente l’esposto contro l’Eternit. Aveva tanta rabbia perché quella che le era piombata addosso la sentiva come una grossa ingiustizia, per sé e per tutti quelli che sono morti, e lei conosceva personalmente. Non solo lavoratori, ma anche cittadini. Dopo il 1980 era morto un maestro elementare. E poi c’è stato il Piercarlo Busto, un parente carissimo della mia famiglia».

Giovanna Patrucco si ferma, raccoglie i pensieri, cerca di dare un ordine: «Forse è paradossale quel che dico – si ferma, prende fiato -: mia mamma ha sofferto più per l’ingiustizia subita che per il dolore fisico della malattia».

PROSSIMA UDIENZA

Alla prossima udienza, lunedì 27 settembre, sarà esaminato Paolo Rivella, consulente della procura.

CHIOSA CONCLUSIVA

Il sindaco Federico Riboldi è convinto, e lo ha detto venerdì ai giudici d’Assise, a proposito dell’immagine di Casale, che «la campagna giornalistica contribuì a diminuire l’appeal della città».

A significare che i numerosi servizi che i giornali dedicarono, negli anni, alle varie battaglie sindacali e ambientali, alle diverse fasi giudiziarie, alle bonifiche con avanzamenti e intoppi, ai solleciti nei confronti della ricerca di una cura e anche alla tragica documentazione delle morti, con le singole storie dolorose delle vittime, ecco questi servizi avrebbero diffuso un’immagine poco bella di Casale, offuscando le bellezze, reali e incontestate, d’arte e paesaggio, che contraddistinguono questo territorio cifrato Unesco.

Non interferisco sulla testimonianza, ma una chiosa è indispensabile. Rispetto il punto di vista del sindaco Riboldi, ma, mentre condivido molte delle osservazioni che ha fatto, su questa dissento con forza.

Dico che se la città di Casale Monferrato è diventata, come tra l’altro ha sottolineato con orgoglio Riboldi in aula, «un simbolo nel mondo», è grazie alla voce instancabile che i giornali e i giornalisti hanno dato alla sua battaglia intrepida e alla sua resilienza dignitosa. Soltanto così si è potuto sapere nel mondo intero che, in questo territorio suggestivo e ricco di bellezze naturali e architettoniche, vive una popolazione fiera e coraggiosa, che tiene su la testa e ritta la schiena.

Ricordo, con amarezza e sdegno, che ci sono state molte iniziative e molti tentativi per tacitare le voci, relegandole al più a un fastidioso rumor, come era scritto e auspicato nel famoso «Manuale» dell’Eternit che addestrava a mistificare e minimizzare i danni nefasti dell’amianto. I giornali e i mezzi di informazione di questa terra non si sono lasciati zittire e, forse, proprio questo è l’aculeo più fastidioso per chi – più o meno consapevolmente, lo decideranno i giudici – tanto dolore ha causato.

Traduzione a cura di Vicky Franzinetti

SILVANA MOSSANO

Eternit Bis trial, September the 20th 2021 hearing

A DETAILED ACCOUNT ON REMEDIATION, THE MAYOR OF CASALE AND THE STORY OF THE BAKER’S DAUGHTER

- REMEDIATION

A few years ago, the Municipality of Casale advertised a position for the head of the town’s technical department. In the end, the candidate who was selected did not accept the position despite it being permanent and secure, for fear of moving to the city of asbestos. We will never stop saying Casale Monferrato is not the city of asbestos, it is the city that has fought and reacted against asbestos; it has done so for itself and for all those other cities in the world that have been unjustly and unknowingly intoxicated by the carcinogenic fiber. There is no place in the world more aware than Casale, and where more reclamations have been carried out: fear, however, lingers on.

The fact was mentioned at the hearing of the Eternit Bis trial on Friday, September 20th, which is being held in the Court of Assizes (Chief Judge Dr Gianfranco Pezzone, with Judge Manuela Massino and popular judges or Jury), against the defendant Stephan Schmidheiny, accused of having deliberately caused (voluntary or willful homicide) the death of 392 people in Casale. The asbestos used in the manufacturing of sheets and pipes at the Eternit plant – overlooking via Oggero al Ronzone and that the Swiss entrepreneur managed directly from 1976 to 1986 – is the object of the trial.

“The remediation program in Casale started in 1997 with the arrival of the special fund,” stated architect Piercarla Coggiola, who since then has been in charge of the project, and since 2010 is manager of the Ufficio Ambiente Ecologia (Environment Ecology Office). Mayor Federico Riboldi, also a witness at the trial, also stressed that ” the creation of an autonomous Environment Department devoted primarily to remediation is a peculiarity of Casale and there is no equivalent in medium-sized municipalities comparable to ours”.

Extremely precise and accurate, and above all with the kind of knowledge those who actually worked in the field have, Architect Coggiola described the phases chronologically, the milestones of the path to freedom from asbestos. “Asbestos free” is what the community of Casale yearns for. And the town is getting there. The reclamation plan started in 1997, “but, already before, the administration had purchased the former Eternit Warehouses of Piazza d’Armi with its own funds, reclaimed it and transformed into a multiplex cinema and exhibition centre”. Moreover, with the approval of the Eternit bankruptcy judge and administrator, the town of Casale purchased the main body of the former manufacturing plant in Via Oggero (abandoned in 1986) and the so-called “Ex Piemontese” area.

“By 1994 – specified architect Coggiola – we had developed the Urban Plan and participated in a European call for bids to obtain funds for reclamation, air monitoring and a dedicated asbestos landfill. Unfortunately, however, it was not approved”. Useless? Not at all: “It was later used to apply for funds from the so-called Seveso Plan, in 1997”. A perimeter of 48 municipalities was drawn, corresponding to the health area of the former health district 76, with Casale as the leader (in 2000 it became “SIN”, i.e. Site of National Interest), covering an area of 740 square kilometers. “Overall, in all these years, 120 million € have been allocated for diversified remediation interventions, of which 64 million came from the National Government in 2015” after the disappointment of the Cassation ruling of the Eternit One trial.

- The Eternit Plant

The City purchased the plant in 1995 and immediately investigated what remediation work was required. As soon as news of the assignment of funds reached the municipality in October 1997, the executive project was approved and the tender was launched, but it was blocked because the Decam Company that came 2nd in the tender appealed. In the end it won the appeal, but then came across too many difficulties. As a result “Arpa (the regional environmental agency) and the health authority divided the area into different sectors, ands a specific plan was prepared “. Did everything go smoothly from then on? No, because we found more asbestos than had been foreseen, which lengthened time and red tape. In the end the plant was reclaimed and demolished, buried under a concrete bed that the Casalesi called the “esplanade“. “Total cost of the intervention is around 7 to 8 million €”.

- “Eternot” Park

Above the esplanade, the Eternot Park (i.e. No Eternit) was built costing between 4 and 5 million Euros – inaugurated on September 10, 2016, “very important for the community of Casale so much so that, we celebrate the birthday of this symbolic place every year”. The building of the park was also littered by disputes with the Coutenza of the Lanza and Mellana Canals, because they found asbestos in the slush on the bottom and on the banks of the Lanza Canal (the 1st lot, reclaimed in October, and in autumn 2002 the third was concluded) . Then scrap and dust were discovered in some sheds that Eternit had sold privately (which was reclaimed in a very approximate manner ).

- Former office building

The town council, then led by Mayor Riccardo Coppo, stated it would re-zone the area if an agreement was not found, bought the plant from the Eternit bankruptcy with the specific intention of cleaning it up as it was estimated that no person or private company ever would. The office building was excluded, assigned to another creditor, who then went bankrupt. A new hurdle. Years and administrations went by, until the Municipality purchased it for 63,000 €, and reclaimed the area making it safe. “We found a lot of dust in there, everywhere, even on a desk, on sheets of paper and abandoned pens,” recalled the architect Coggiola. There are still tests to be completed before the building can be used as a multipurpose center for museum, youth and teaching activities. Coggiola also spoke about the serious pollution identified in the area of Ex Piemontese, where the crushing of waste took place. A part is asbestos-free and the Verdeblu nursery school has been built there. Another area, further away, has yet to be reclaimed.

- The “little beach”

“The beach was created by the waste expelled from the Eternit drainage channel, which ended up in the Po, on the right bank,” explained the witness. “It was one of the most dangerous areas, very exposed and extensive: 6,500 square meters with a depth of 5 meters. The reclamation project began in 1998 and was completed in 2000. “We could not remove the material, so a sarcophagus was built using an innovative technique based on injections of liquid concrete into the ground.” Coggiola recalled that “very shortly after the completion, in October 2000 we had a flood; well, it was a sort of test: the building held.” Afterwards, it was wilded or re-naturalized and you can’t see the difference with the rest of the landscape anymore.

- The Bagna Landfill

“We used to think of this area along the shore of the Po, left bank, as a polluted site for spilling different types of chemical waste and, as such, we thought of reclaiming it. However, after the 2000 flood, when excavations were made to extend the bridge over the River Po, asbestos was also found in the Bagna landfill” explained the manager. And we had to reclaim that, too.

- Holiday Huts along the River

Throughout time people had build little holiday huts along the river. However, they often used asbestos sheets to build them. “We are monitoring the shacks, trying to identify their owners or understand whether they are still in use.” One, in particular, the so-called “Radames’ shack”, named after its owner, required immediate remediation: “It was dilapidated, with walls made of asbestos and dust in the basement. It was reclaimed, demolished and, in its place, a small raised belvedere was created with a view on the river Po River”.

- “Eternit” Roofs

Over the course of more than two decades, a census, in fact several were carried out. The asbestos roofs of public buildings in the 48 municipalities of the “SIN” area have been almost all removed and replaced. Examples: former Eternit warehouses, schools, fruit and vegetable market (which has recently been demolished), library, Natal Palli stadium, Santo Spirito Hospital, Surgeries in Via Palestro, the barracks and others in the villages. Many private citizens, encouraged by the funds made available for the removal and, with the strength of a widespread and massive awareness campaign (not unrelated to the magnitude of the health problems), have reclaimed houses, sheds and small areas such as chicken coops and sheds. “You can still make requests for contributions – explained the manager -: we will reclaim asbestos while there is still any.”

- Dust

This is the most damning. Production waste that has been found in the most disparate places: in the square of Ticineto (“where a ‘wet’ method was tested that we had to invent here”), in the driveways of the cemetery of the same town, at the former palace Cova Adaglio now Media Trevigi, in the courtyard of the castle Paleologo, at the Ecomuseum Pietra da Cantoni in Cella Monte, in the churchyard of Odalengo Grande, in bowling greens, in the courtyards of apartment buildings, in the foundations of squares and private roads, in the basement of the retirement home and in the basement of the Leardi High School (the latter was taken over by the Province).

- Dedicated Landfill

“The Municipality of Casale has given up selling desirable lots (value one million and 400,000 €) in the industrial area of Valenza street to allocate them to the realization of a specific landfill for asbestos, with diversified tanks for disused slabs and powder. The landfill was built in 2001 and is directly managed by the public body: it is a rare case, usually private companies manage them” explained architect Coggiola, who is the technical manager of the plant. “A fundamental tool” – she pointed out – “that allowed to carry out, speed up, incentivize and contain the costs of asbestos reclamations”. The regional Arpa (Environmental Agency) performs spot inspections, to monitor the management.

- MAYOR RIBOLDI

Federico Riboldi, mayor of Casale since 2019, was born in 1986, the same year the Eternit factory was closed, or rather abandoned after the bankruptcy requested by the same company, after 80 years of activity. Continuing in the wake of the administrations that preceded it, the Riboldi administration is still facing the consequences of that industrial activity. The mayor testified to this at the Assize hearing on Friday, September 20, highlighting “the great effort of the community of Casale and the administrations that have followed, making this city a symbol in the world and an example for asbestos abatement. Prosecutor Gianfranco Colace asked the Mayor for an account of the costs that the community has had to bear. “The first great price, incalculable, is undoubtedly that of the victims, with the wake of immense pain and an impoverished population.” Riboldi then recalled the expenses incurred even with resources drawn from municipal budgets, “both for acquisitions and for legal disputes” as well as for the renunciation of collecting adequate sums from the sale of industrial lots that were instead chosen to be used for the construction of the landfill for asbestos. Riboldi also dwelt on the “damage to the town’s image caused by asbestos with strong negative effects that have blocked some developments, have discouraged the establishment of businesses and new families because of fears generated by asbestos pollution, have affected school and sports activities and, very much, the tourist attraction”. The mayor then pointed out how the administrative practices of various kinds in support of the reclamation have slowed down the activity of the municipal machine in several areas. “The most terrifying thing – he insisted – is that they left an ecological time bomb of this type near homes, schools, in the midst of people.” And did Schmidheiny, or anyone connected to companies in his group, ever offer to help with the cleanup, inquired prosecutor Colace. “Not to my knowledge, no.” However, a somewhat unusual bargaining there was, “in November 2017, when I was vice- president of the Province, the representative of a company in the health sector, knowing that I am from Casale, approached me proposing an unspecified job on the image of the territory of Casale.” And how did it go? “I spoke informally with Dr. Daniela Degiovanni, and she suggested that before starting any discussion, I should tell this person that, he should put in writing that he had no connection with Schmidheiny or Eternit. I followed the advice and sent him a whatsapp. Then he never contacted me again.”

- THE BAKER’S DAUGHTER

“My Mom was diagnosed with mesothelioma in November 2001. And she immediately said: ‘There’s nothing to say, we know everything'”. The daughter of Giovanna Patrucco, who lived in Ronzone, at number 61 of via Oggero (and still lives there a few numbers away), graduated in Chemistry, worked as manager first at the Mauriziano Hospital in Turin and then at the Sant’Andrea Hospital in Vercelli, spoke about the Eternit district during the decades in which her parents managed the food store not far from the factory. “We used to live in the backroom, at that time, that was how it was for those who had a food store. Many workers were our customers and they bought bread, cheese, salami, ham. We knew them well by name and a degree of friendship developed “. Her mother was very scrupulous in trying to keep the food clean, especially the loaves of bread displayed in baskets, and used a broom to brush off the dust from her customers’ overalls, brushing away some of the dust before letting them into the store. “The dust,” she explained, pressed by questions from Prosecutor Mariagiovanna Compare, “was like a front door in Ronzone. It was everywhere. When the shutters had to be repainted, my mom said, ‘Let’s make them gray, so you can’t see the dust!'” The witness’s memory is clear : “I remember everything. The courtyards were covered in dust, and so were the sidewalks and the slats of the shutters; the streets were buried in it, the dust even hid the tracks of the “tramvajin” (the trolleybus) and my parents told me to be careful when I rode my bicycle so I wouldn’t end up on the tracks. The shoes, too, “how angry I was that they were dusty before I got to school!” And the former Piemonte District ? “There the waste was crushed and flew up in clouds. Many people used the waste; at my house, for example, they bordered the flowerbed. Instead, the courtyard of the neighbor, Bruno Besso, who later died of mesothelioma, had been leveled with the dust. Then there was the “little beach”: “Oh, yes, when we were children we used to go swimming, and when we were teenagers we used to sunbathe. And on Sundays we’d have barbecues. For us it was a little Riviera.” Dust, dust and announcements of deaths. “In my house you could sense that something was wrong; there was a sense of alertness.”

Her mother’s mesothelioma diagnosis was a shock, but not really a surprise-“we know everything anyway…” “My mother was aware of what awaited her and wanted to personally sign the complaint against Eternit. She was so angry because she felt that what had befallen her was a great injustice, for herself and for all those who had died, and whom she knew personally. Not only workers, but also citizens. After 1980, an elementary school teacher had died. And then there was the Piercarlo Busto, a very dear relative of my family.” Giovanna Patrucco stops, gathers her thoughts, tries to order her thoughts: “Maybe it is paradoxical what I am saying – she stops, takes a breath -: my mother suffered more for the injustice she suffered than for the physical pain of the disease”.

4) CONCLUDING REMARKS by Silvana Mossano

Mayor Federico Riboldi is convinced, and said so on Friday to the Assize Judges, that “the journalistic campaign contributed to diminishing the city’s appeal” (ref to Casale’s image). The many newspaper articles dedicated, over the years, to the various union and environmental battles, to the various judicial phases, the reclamation, to the calls to search for a cure and also to the tragic documentation of the deaths, with the individual painful stories of the victims, all this would have spread a not very nice image of Casale, obscuring the beauties, real and uncontested, of art and landscape, that distinguish this area listed as a World Heritage Unesco site.

I do not question his testimony, but a comment is indispensable. I respect Mayor Riboldi’s point of view, but while I share many of the observations he has made, I strongly disagree with him on this one. I say that if the city of Casale Monferrato has become, as Riboldi proudly pointed out in the courtroom, “a symbol in the world,” it is thanks to the tireless voice that newspapers and journalists have given to its intrepid battle and dignified resilience. This was the only way to let the whole world know that, in this evocative territory rich in natural and architectural beauty, there lives a proud and courageous people that keeps its head up and its back straight. With bitterness and indignation, I remember that there have been many initiatives and many attempts to silence us, relegating them at most to an annoying rumor, as it was written in the famous “Handbook or Manual ” of Eternit that sought to mystify the damage of asbestos. The newspapers and the media of this land were not silenced and, perhaps, this is the most annoying sting for those who – more or less knowingly, the judges will decide – have caused so much pain.

NEXT HEARING

At the next hearing, on Monday, September 27, Paolo Rivella, the prosecutor’s financial consultant, will be examined.

Continua la tua narrativa puntuale e precisa su quando accaduto nel nostro territorio da molti anni e ancora succede. Giusto processo e sentenza mai più ripagata per chi non è più con noi a cui rivolgo un ricordo nella preghiera. Grazie Silvana

Cara Silvana grazie per il resoconto così ricco e pieno di temi per riflettere. Per me è sempre terribile toccare l’argomento Eternit. Nonostante le grandi cose fatte dai cittadini, dalle Istituzioni e da te con le tue denunce e i resoconti, il dolore torna ogni volta che se ne parla. E questo è un bene. Perché soltanto se si attraversa il dolore si reagisce con forza ad un’ingiustizia così enorme. Mi ha colpito la testimonianza della dottoressa Patrucco. Ho conosciuto persone che come lei andavano a giocare e a fare il bagno sulla “spiaggia della morte”. Non ci sono più. Mi auguro solo che questo processo si concluda presto e possa vincere la Giustizia.

Grazie Silvana, per il tuo costante impegno a scrivere in modo puntuale e preciso, sulla tragedia che ha colpito la nostra comunità.

Come sempre la tua ricostruzione dei fatti è precisa e molto dettagliata. La leggi e ti resta dentro. Non si potrà dimenticare, non si deve dimenticare.

Condivido in pieno il tuo punto di vista sull’importanza dell’informazione per continuare la lotta contro le conseguenza dell’amianto. Se lo diciamo a voce alta ci verrà sempre più riconosciuto questo ruolo di città ‘faro’ per il mondo. Di città fortissima e bellissima. Di comunità solidale, che sa rincuorare tutti quelli che soffrono per l’amianto

I tuoi scritti sono di una precisione unica, purtroppo tu hai conosciuto il problema da vicino. È impressionante ripercorrere le tappe di questa vicenda e non avere ancora una giustizia “giusta”e altrettanto lo sono i racconti dei diretti interessati. Mi ha molto colpita la testimonianza di Nicola Pondrano, non si può dimenticare. Speriamo che non vengano dimenticati nemmeno i tanti, troppi morti