SILVANA MOSSANO

Reportage udienza 31 gennaio 2023

«Originale». E’ partita da qui la requisitoria del pubblico ministero Gianfranco Colace: dal significato della parola «originale» usata dall’avvocato Astolfo Di Amato (difensore di Stephan Schmidheiny, insieme al collega Guido Carlo Alleva) per definire il capo di imputazione in cui il suo assistito «in qualità di effettivo responsabile della gestione della società Eternit spa, esercente gli stabilimenti di lavorazione dell’amianto siti in Cavagnolo, Casale Monferrato, Napoli-Bagnoli, Rubiera (…)» deve rispondere, davanti alla Corte d’Assise di Novara, dell’omicidio volontario, con dolo eventuale, di 392 casalesi: 62 ex lavoratori della fabbrica che aveva sede nel quartiere Ronzone (in via Oggero) e 330 che, semplicemente, vivevano in città e dintorni.

L’avvocato Di Amato è molto attento e puntuale nell’utilizzo delle parole: «Un capo di imputazione originale» aveva detto. Il pm Colace ha soppesato questa definizione. E l’ha fatta propria, ma non associata all’imputazione: «Ciò che è originale – ha esordito – è la vicenda di Casale Monferrato. E poiché, per definizione, l’originale è l’esatto contrario di una copia, ecco… non c’è una vicenda di malattie asbesto correlate che sia una copia paragonabile a questa: quella di Casale è una vicenda unica al mondo».

Scandisce le parole e il linguaggio è pacato, perché non serve enfasi per descrivere la realtà: «Casale è una città martire dove si è consumata – e si consuma – una strage silenziosa di 392 vittime. 392 vite. 392 famiglie». E aggiunge, buttando un breve sguardo alle sue spalle: «Colpisce molto la compostezza della gente che piange i propri morti. La vedete, è qui, in silenzio, ed espone, fuori, dei cartelli non di protesta, ma più come monito ai ragazzi che in questo palazzo, dove celebriamo il processo, frequentano l’università».

COMINCIA LA DISCUSSIONE

Dopo 36 udienze di dibattimento, l’Eternit Bis ha dato avvio alla fase della discussione, cominciata lunedì 30 gennaio con la requisitoria dei pubblici ministeri Colace e Mariagiovanna Compare. Proseguiranno venerdì 10 febbraio; poi, ci saranno le udienze dedicate alle arringhe dei legali di parte civile (20 e 27 febbraio) e quelle per i difensori (10 e 29 marzo).

Il pm Colace vuole far comprendere bene ai giudici (il presidente Gianfranco Pezone, il magistrato togato a latere Manuela Massino e i sei giudici popolari) che «comunque vada a finire, con questo processo si scrive una pagina di storia che riguarda lavoratori e cittadini non solo di Casale, ma di tutto il mondo».

La stima è che i mesoteliomi nel mondo siano nell’ordine di grandezza di 50 – 100.000 all’anno.

Colace parla di strage: «Si dice che è stata determinata dall’amianto. No – puntualizza -, questa è una strage dovuta all’uomo ed è il simbolo macabro di una certa imprenditoria che ha un po’ il carattere del colonialismo». Poi, con lo sguardo fisso alla Corte: «Riteniamo ci siano le prove che di queste morti sia responsabile Stephan Schmidheiny. E ci proponiamo di spiegarvi perché».

REQUISITORIA IN 4 PARTI

La requisitoria viene suddivisa in 4 capitoli: 1) la condotta (in che condizioni l’amianto è stato usato e trattato); 2) l’evento (la dimostrazione che tutti e 392 sono stati decessi dovuti a mesotelioma); 3) il rapporto di causa (come ha inciso su quei decessi l’esposizione all’amianto nel decennio 1976-1986, quando l’imputato era l’effettivo responsabile nella gestione dell’Eternit); 4) l’elemento soggettivo, cioè l’analisi dell’atteggiamento di Schmidheiny: «Sapeva e ha accettato che tutto ciò accadesse o è stato solo imprudente? Siamo certi di poter dimostrare la condotta che si configura nel dolo eventuale» ha dichiarato il pubblico ministero.

PROCESSO DIFFICILE

Si devono affrontare e risolvere problemi di tipo scientifico e giuridico.

Colace si sofferma sul primo dei due aspetti: «I consulenti tecnici sono i portatori della scienza nell’aula di giustizia, ma non devono essere né accusatori né difensori, perché i giudici hanno bisogno del supporto della scienza, non di punti di vista personali. Poi – commenta – i consulenti possono fare quello che vogliono, ma, se non si attengono alla scienza, non sono credibili». A parere del pm, «i ct della difesa, invece, hanno dimostrato un eccesso di zelo difensivo che ha fatto scempio della logica». E ancora: «Abbiamo assistito spesso a una contrapposizione tra scienza e punti di vista eccentrici, a volte personali, finalizzati sempre e solo a contestare gli studi scientifici esposti dai ct della procura i quali, invece, questi studi li hanno fatti non per il processo, ma prima, osservando e analizzando dei fenomeni secondo criteri scientifici. Eppure, in quest’aula, sono stati attaccati come se avessero sbagliato tutto…».

Secondo la ricostruzione degli esperti della difesa, infatti, verrebbe fuori un quadro in cui «tra il ’76 e l’86 (periodo di gestione dell’imputato, ndr) non c’era quasi amianto nello stabilimento, tutto era sotto controllo, e che all’esterno della fabbrica le uniche fibre diffuse erano quelle dei battuti e del polverino (e chi mai lo aveva distribuito? Ah, be’, lo aveva distribuito chi era responsabile dell’Eternit prima di Schmidheiny!), e anche che in quel decennio a gestire effettivamente la società non era Schmidheiny stesso bensì i dirigenti, e che quasi quasi quei morti non sarebbero neppure tutti morti di mesotelioma… forse i medici casalesi hanno esagerato nel fare le diagnosi… Ma allora – è la domanda del pubblico ministero -: perché siamo qui?».

«PERCHE’ SIAMO QUI?»

«Perché la realtà è diversa – dichiara Colace -: a Casale c’è stata, e ci sarà ancora per anni, un’epidemia di mesoteliomi. E non ci sono state sopravvalutazioni o errori medici: Casale non è una città martire della malasanità, ma è una città martire dell’amianto».

Ciò che non dà pace è che «quella epidemia si sarebbe potuta evitare, o almeno si sarebbe potuto limitare l’impatto della strage».

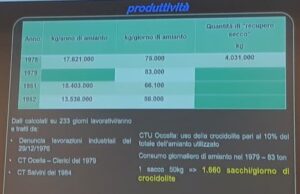

Colace ripercorre la storia dell’Eternit, il passaggio dalla gestione prevalentemente belga (della famiglia Emsens/de Cartier) a quella svizzera (della famiglia Schmidheiny); ricorda che i manufatti (a Casale, lastre e tubi) si facevano con un impasto di cemento e amianto; che l’amianto era la materia prima impiegata nel ciclo produttivo in quantità massicce. Era utilizzato sia l’amianto bianco (crisotilo) che l’amianto blu (crocidolite, il più pericoloso); quest’ultimo in una proporzione del 10% dell’impiego complessivo (oltre 1600 sacchi da 50 kg ciascuno al giorno).

«PRECAUZIONI NON RISPETTATE»

Secondo il pubblico ministero, in un settore produttivo così delicato per la salute dei lavoratori e la salubrità ambientale, «non è stata rispettata nessuna delle precauzioni di sicurezza sul lavoro (peraltro già indicate nel Dpr 303 del 1956)».

Qual era la situazione in fabbrica? «Catastrofale» la definì un alto dirigente nel 1973. E più avanti? Un altro dirigente, nel 1975, descrive «un ambiente sporco, polveroso, disorganizzato nella programmazione della manutenzione e nella gestione degli impianti di aspirazione». E poi? «Nel 1976, Klaus Robock, scienziato che lavora per il gruppo Eternit, in una nota interna, successiva a un sopralluogo a Casale, rileva difetti e problematiche “su cui occorre intervenire”».

Come si interviene?

La difesa, tramite i propri consulenti, ha affermato (e sarà certamente un argomento che verrà ripreso nelle arringhe) che Stephan Schmidheiny fece arrivare all’Eternit italiana molti flussi di denaro. Colace è scettico; «intanto, a ogni processo le cifre indicate dalla difesa continuano ad aumentare»; inoltre, «il nostro consulente ha ricostruito l’entità e la destinazione di quei flussi; ebbene, servirono più per coprire perdite che non per investire in sicurezza». Non che non si sia investito per niente, ad esempio sicuramente in nuovi impianti e nel passaggio dalla lavorazione secca a umida; ma la quantificazione degli investimenti specifici per la sicurezza, ricostruita dal consulente dell’accusa, si attesta «su 4 miliardi di lire, spesi in un decennio e spalmati tra tutti gli stabilimenti Eternit italiani». Un importo distante da quello indicato dai ct della difesa.

BUSINESS DELL’AMIANTO SOTTO ATTACCO

L’industria dell’amianto, negli anni Settanta, cominciava a sentire il fiato sul collo. Nel 1964, lo scienziato Irving Selikoff, al Simposio internazionale dell’Accademia delle Scienze di New York, aveva lanciato l’allarme (non il primo, peraltro) evidenziando chiaramente il nesso causale tra amianto e mesotelioma. L’amianto causa il mesotelioma, e di questo cancro maligno si muore; e non riguarda soltanto i lavoratori del settore, ma chi respira le fibre diffuse nell’aria. Reazione dell’industria dell’amianto? Selikoff è da ignorare, non va neppure citato il suo nome.

La Johns & Melville americana, tra l’altro, era stata fortemente piegata dagli stratosferici risarcimenti a numerose vittime dell’amianto che era stata costretta a pagare (fallisce poi negli anni Ottanta). Lavoratori, sindacalisti, giornalisti, medici, politici cominciano a fare domande, troppe domande.

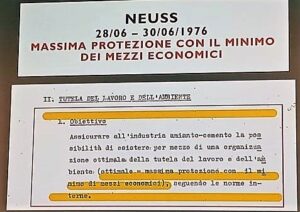

E quindi? «L’imprenditore fa una scelta: predilige l’affare e si difende dagli attacchi sferrati al proprio business». E come? Colace richiama il convegno di Neuss, nel 1976, presieduto da «Schmidheiny in persona», il cui obbiettivo era il seguente: «Assicurare all’industria amianto-cemento la possibilità di esistere per mezzo di una organizzazione ottimale della tutela del lavoro e dell’ambiente seguendo le norme interne», dove «ottimale», si legge in un verbale dell’incontro cui parteciparono i massimi dirigenti dell’Eternit, è uguale (=) a «massima protezione con il minimo dei mezzi economici».

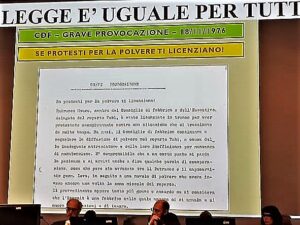

E chi reagisce? Chi si ribella (magari in modo scomposto perché esasperato) viene licenziato.

Nel testo qui a fianco, è riportato uno stralcio di un comunicato del Consiglio di fabbrica, datato 18/11/1976, titolato «Grave provocazione». Il testo: «E’ stato licenziato in tronco per aver protestato energicamente contro una situazione che si trascinava da molto tempo. Da mesi il consiglio di fabbrica continuava a segnalare la diffusione di polvere nel reparto Tubi a causa delle inadeguate attrezzature e della loro inefficienza per mancanza di manutenzione. E’ comprensibile che a un certo punto si perda la pazienza e che si arrivi a dire qualche parola di esasperazione tra (…) in seguito a una nuvola di polvere che aveva invaso ancora una volta la zona miscele del reparto. Il provvedimento appare tanto più grave se si considera che l’Eternit è una fabbrica nella quale ancoraci si ammala e si muore di asbestosi e di tumore».

E a chi insiste? Viene fornita la spiegazione placebo di «Casale 3», riguardante il progetto di costruire uno stabilimento nuovo e in sicurezza nella zona Industriale, alla periferia di Casale. Riccardo Coppo (il sindaco che, nel 1987, aveva firmato la famosa ordinanza che vietava l’amianto a Casale) testimoniò al Maxiprocesso Eternit nel 2011: «A un certo punto abbiamo capito che ci stavano prendendo in giro» e scrisse una lettera all’azionista di maggioranza dell’Eternit per comunicargli che era «fortemente preoccupato per il calo occupazionale nella fabbrica, per il grave degrado dello stabilimento, ma soprattutto per le conseguenze gravi che la lavorazione dell’amianto aveva sulla salute di lavoratori e cittadini». La lettera è datata 24 settembre 1985. L’azionista di maggioranza era Stephan Schmidheiny.

Il pubblico ministero richiama, poi, Auls76, il «manuale della disinformazione» lo definisce, in cui sono elencate in dettaglio diverse ipotesi di circostanze critiche con le relative risposte che andavano date a seconda di chi poneva domande sull’amianto (appunto lavoratori, vicini di stabilimento, sindacalisti, giornalisti, politici e così via), e si suggerisce di attenersi, come riferimento, alla legislazione tedesca meno restrittiva rispetto ai limiti di polverosità indicati dall’Osha (l’Agenzia americana che si occupa di sicurezza sul lavoro).

«(…) Dal momento che questa diffamazione può mettere a repentaglio l’esistenza della nostra industria, dobbiamo reagire in maniera decisa e dobbiamo combattere con tutti i nostri mezzi»

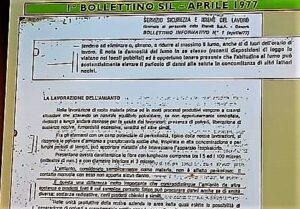

«Schmidheiny differenzia il tipo di informazione: quella da fornire ai massimi dirigenti, chiara sui rischi reali dell’amianto, e quella per i lavoratori, edulcorata, confusa». In una («l’unica») comunicazione diretta ai lavoratori viene scritto: «L’amianto non è affatto pericoloso: il contatto manuale con esso non apporta alcun danno». C’è invece il fumo che…

«(…) eliminare o almeno a ridurre al massimo il fumo. E’ nota la dannosità del fumo in sé stesso (…) ed è opportuno tenere presente che l’abitudine al fumo può sostanzialmente elevare il pericolo di danni alla salute in concomitanza di altri fattori nocivi» [Non si fa nessun riferimento all’amianto]. L’amianto, invece, al contatto «non è pericoloso (…), a differenza di altre sostanze o prodotti «il cui semplice contatto fisico può produrre danni (…): sostanze radioattive, certi prodotti chimici e simili».

MA LA POLVERE C’E’ O NO?

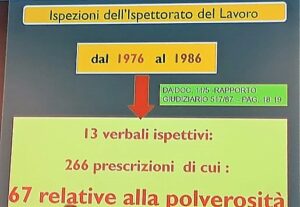

Il pm Colace richiama testimonianze puntuali (tra cui quelle dei sindacalisti Nicola Pondrano e Bruno Pesce, e di lavoratori), documenti, ispezioni (dell’Ispettorato del lavoro, finalmente), perizie che attestano la presenza di una polverosità ubiquitaria, diffusa in tutti gli spazi della fabbrica.

Per contro, i consulenti della difesa hanno ricostruito una situazione diversa che il pubblico ministero stigmatizza così: «Vogliono far credere che lo stabilimento era lindo come la sala operatoria di un ospedale! Hanno raffigurato una situazione non realistica, enfatizzando alcuni dati e tacendone altri».

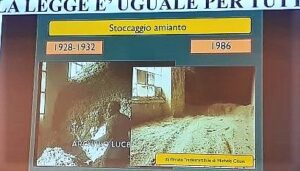

Lancia sullo schermo due fotografie appaiate: una si riferisce al fermoimmagine di un filmato Luce che propone l’ambiente lavorativo tra gli anni 1928 e 1932; l’altra uno scorcio interno della fabbrica quando fu chiusa e abbandonata nel 1986. Si rivolge ai giudici: «Ci portereste i vostri bambini a giocare lì?».

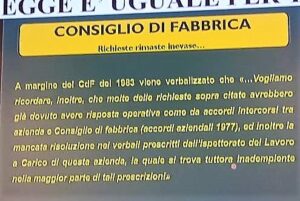

Tra l’altro, il consiglio di fabbrica, nel 1983, richiamava una serie di richieste inevase e sollecitava interventi promessi e disattesi, incluse le prescrizioni impartite dall’Ispettorato del lavoro su cui l’azienda, a distanza di anni, era ancora inadempiente.

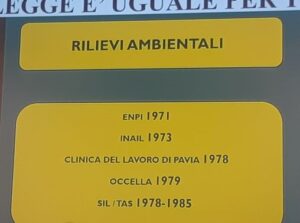

E, tuttavia, l’Inail si era fatta convinta che lo stabilimento di Casale fosse virtuoso, con la polvere perfettamente sotto i limiti di legge, tanto che aveva esentato la società dal versamento del «sovrappremio» legato ai rischi di malattie asbesto correlate. La conseguenza fu che i lavoratori non avevano più diritto alla cosiddetta «rendita di passaggio», che consentiva di andare in pensione con un anno di anticipo. I sindacalisti Pondrano e Pesce si mobilitarono, furono promosse cause all’Inail davanti al giudice del lavoro; lì si scoprì la questione del sovrappremio non più versato dall’azienda a seguito di accampate motivazioni di miglioramento delle condizioni ambientali e conseguente abbattimento del rischio di ammalarsi di asbestosi (malattia amianto-correlata, dose-dipendente). Il pretore Giorgio Reposo si trovò di fronte al dilemma: «Ma c’è o no la polvere dentro la fabbrica?». La risposta gliela diede il consulente Michele Salvini, professore universitario di Pavia, che la polvere la trovò, eccome; dove? Dove non si era pensato di far pulire accuratamente in previsione dell’ispezione. Le cause per la rendita di passaggio davanti al pretore, per inciso, furono tutte vinte dai lavoratori.

Colace insiste: «La polvere d’amianto era diffusa dentro lo stabilimento e fuori».

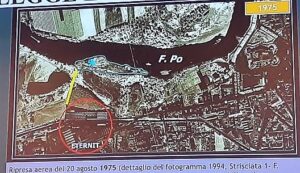

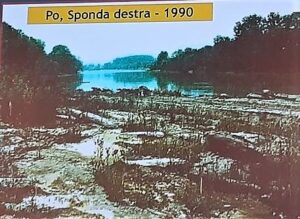

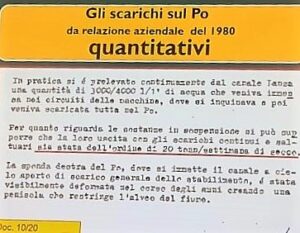

Elenca esiti di monitoraggi e mostra fotografie: i ventoloni di aspirazione posizionati su un muro della fabbrica che buttavano fuori le polveri senza filtraggio; l’area ex Piemontese della frantumazione degli scarti con la ruspa e a cielo aperto; l’assenza di lavanderie interne per evitare che gli operai e le operarie tornassero a casa con gli abiti da lavoro («fermandosi a comprare il pane, a prendere i figli a scuola e a tenerli in braccio con tutti quei puntini bianchi di polvere tra i capelli…»); i trasporti su camion, per le vie della città, dei sacchi contenenti la materia prima che arrivava alla stazione ferroviaria e dei manufatti finiti trasferiti ai magazzini di piazza d’Armi; gli scarichi delle acque reflue contenenti amianto sulla sponda destra del Po: qui formarono una crosta molto spessa, la famosa «spiaggetta», meta domenicale di molte famiglie che la consideravano la loro «riviera» sul fiume.

«Per quanto riguarda le sostanze in sospensione si può supporre che la loro uscita (…) sia stata dell’ordine di 20 tonn/settimana di secco. La sponda destra del Po dove si immette il canale a cielo aperto di scarico generale dello stabilimento è stata visibilmente deformata nel corso degli anni creando una penisola che restringe l’alveo del fiume»

E, sulla sponda sinistra del Po, c’era la discarica Bagna. Enrico Bagna era l’operatore che aveva l’appalto con l’Eternit per portar via dallo stabilimento e smaltire scarti e rifiuti di lavorazione, tra cui ingenti quantitativi di polverino.

LA DIFFIDA

«Nel 1979, l’Eternit mandò una diffida a Bagna perché non vendesse più il polverino ai cittadini che lo utilizzavano per battuti (di campetti sportivi, cortili, strade…) e come coibente nei sottotetti. «Intanto, – spiega il pubblico ministero – la diffida dimostra che la distribuzione di polverino non era stata vietata con l’inizio della gestione Schmidheiny, nel 1976, contrariamente a quanto i consulenti della difesa hanno detto sul fatto che il polverino degli “usi impropri” in città era stato ceduto da chi aveva gestito l’Eternit prima di Stephan Schmidheiny. Inoltre, se si vieta a Bagna di cederlo è perché si sa che è molto pericoloso… contiene crocidolite tra l’altro… E che si fa? Si diffida Bagna, ma si tace alla popolazione anziché metterla in guardia del grave pericolo che sta correndo!». Non solo: il poverino, portato via come rifiuto e scarto dalla fabbrica, quand’anche non fosse più stato ceduto alla popolazione, continuò a essere scaricato, «almeno fino al 1984», nella discarica in sponda sinistra del Po: «A cielo aperto, libero di disperdersi nell’aria…» rimarca il pm.

COME SI COMPORTA L’AMIANTO?

Già, come si comporta? Dice Colace: «Abbiamo colto delle contraddizioni tra i consulenti della difesa: chi sostiene che dentro lo stabilimento la polvere cade e si sedimenta attorno alla postazione di lavoro senza disperdersi; e chi, riferendosi invece all’ambiente esterno, afferma che le fibre dei polverini e dei battuti si propagano ampiamente». Com’è la questione? «Quello che torna utile affermare per l’interno della fabbrica non va bene per l’esterno?». E poi non gli va giù il paragone tra l’intensità dell’inquinamento prodotto da polverini e battuti e quello della fabbrica e dell’area di frantumazione: davvero sono equiparabili? Davvero l’incidenza delle fibre provenienti dai siti lavorativi è uguale (o addirittura inferiore, secondo il ct della difesa) a quella dei cosiddetti «usi impropri»? «Dobbiamo credere – domanda il pm – che i problemi di inquinamento da amianto a Casale siano stati originati per lo più da quei “buchini” tra una tegola e l’altra dei tetti, come ha affermato un consulente della difesa? E la tegola rotta, poi… una caduta di stile che da un professore universitario non mi sarei aspettato!». Si riferisce al fatto che uno degli esperti, a compendio della propria relazione, aveva mostrato la fotografia appunto di una tegola rotta, quale esempio concreto, secondo la sua tesi, di un tetto ammalorato e della possibile fuoriuscita di fibre dalla sottostante coibentazione. Solo che quella ricostruzione era irreale; infatti, i tecnici dell’Arpa, che avevano scattato quella immagine, avevano spiegato che essi stessi si erano trovati costretti a rimuovere la tegola per poter posizionare lo strumento necessario a eseguire il campionamento.

E ADESSO CHE COSA RESTA?

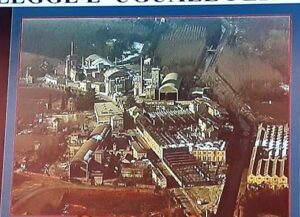

Che cosa resta, ora, dopo 80 anni di attività («l’ultima impennata produttiva fu nel 1981, con la cospicua vendita di manufatti per la ricostruzione dopo il terremoto in Irpinia») e dopo che la fabbrica ha cessato l’attività ed è stata abbandonata (e poi bonificata con i soldi pubblici della collettività)?

«Che cosa resta sul territorio?». Il pubblico ministero ha parlato quattro ore. E’ difficile riassumere e far comprendere una tragedia così complessa usando parole semplici. Prima di sedersi, guarda i giudici a uno a uno e dà una risposta: «Che cosa resta? Restano i 392 casi di morte per mesotelioma».

RESTANO I MORTI

«In questo processo sono 392 le vittime – puntualizza la pm Mariagiovanna Compare -, ma è soltanto una selezione di un numero molto più alto».

Si stimano, complessivamente, almeno 3000 morti a Casale e dintorni. L’incremento attuale si mantiene su circa una cinquantina di nuovi casi all’anno. Tempo addietro, il sindaco Riccardo Coppo aveva detto: «Qui non si ha una percezione immediata della dimensione della tragedia, perché è uno stillicidio lento e continuo».

Se ne vanno uomini e donne, sempre più giovani, uno per volta, in silenzio, senza rumore, mestamente e con rassegnazione, perché, come ha ribadito la pm, «ogni diagnosi di mesotelioma è una condanna a morte».

Eppure, «le diagnosi sono state messe in discussione dai consulenti della difesa: secondo loro, senza il ricorso ai più recenti marcatori immunoistochimici, non si può essere certi che fossero mesoteliomi e non invece metastasi di altri tumori primitivi».

Compare fa proprie le argomentazioni scientifiche dei consulenti della procura e delle parti civili: «Non è vero che non si può fare la diagnosi senza l’immunoistochimica e non è vero che le diagnosi più datate sono da buttare».

Intanto, «non esiste un marcatore specifico per il mesotelioma, quanto piuttosto dei marcatori, più o meno sensibili, indicati dalle linee guida internazionali».

In ogni caso, puntualizza il pubblico ministero, «si tratta sempre di una diagnosi multidisciplinare, cui concorrono accertamenti di vario tipo e occorre che a interpretare gli esiti degli accertamenti sia un buon patologo».

Circa l’insinuazione secondo cui a Casale i medici avrebbero forse esagerato con le diagnosi senza approfondire se i mesoteliomi fossero o no tumori primitivi, la pm Compare replica che molte non furono fatte a Casale, ma in ospedali di altre città o di altre regioni, finanche nel centro lombardo dove svolgeva la professione l’anatomopatologo della difesa Massimo Roncalli («e i suoi colleghi non avevano avuto dubbi sulla certezza di quella diagnosi!»).

Passa in rassegna, scheda per scheda, nome per nome: vita, abitudini, passioni e morte di molte delle vittime elencate nel capo d’accusa. Insiste: «Ogni incremento di esposizione aumenta il rischio di ammalarsi e questo incremento si traduce anche in una anticipazione della morte».

«Sono tutti e 392 mesoteliomi – conclude la pm Mariagiovanna Compare -. Nessun dubbio abbiamo noi. E – rivolta ai giudici – nessun dubbio potete avere voi».

La requisitoria dei pubblici ministeri prosegue venerdì 10 febbraio.

* * *

Translation by Vicky Franzinetti

Eternit bis January the 30th 2023 Hearing

by Silvana Mossano

‘Originale‘ (unusual, original but also quirky in Italian T’s N), Public Prosecutor Gianfranco Colace’s indictment: the meaning of the word ‘originale‘ used by the defence lawyer Astolfo Di Amato (for the accused Stephan Schmidheiny, together with his colleague lawyer Guido Carlo Alleva) to define the indictment where his client ‘as the actual manager of the company Eternit spa, operating the asbestos processing plants in Cavagnolo, Casale Monferrato, Naples-Bagnoli, Rubiera (…)’ must answer, before the Court of Assizes of Novara, for the wilful voluntary murder of 392 people from Casale: 62 former workers from the plant that was based in the Ronzone district (via Oggero) and 330 who simply lived in and around the town.

Lawyer Di Amato was very careful and accurate in his choice of words: ‘An original indictment,’ he said. Prosecutor Colace considered this definition and made it his own, not associated with the indictment: ‘What is original,’ he began, ‘is the Casale Monferrato case. Since, by definition, an original is the exact opposite of a copy, well… there is no case of asbestos-related diseases that is a copy comparable to this one: the Casale case is a unique case in the world’.

He speaks clearly spelling it out, his language is calm, because the situation does not require emphasis: ‘Casale is a martyr town where a silent massacre of 392 victims took place – and is still taking place. 392 lives. 392 families’. He adds, casting a brief glance behind him: ‘The composure of the people mourning their dead is striking. You can see it here, witness it, wafting in silence, and outside displaying signboards, not in protest, but more as a warning to the young people who attend university in this building, where we are holding the trial’.

PHOTO: Prosecutor Dr Gianfranco Colace

THE CLOSING SPEECHES START

After 36 hearings, the Eternit Bis trial closing speeches started on Monday, January the 30th 2023 with the indictment of prosecutors Colace and Mariagiovanna Compare. They will continue on Friday, 10 February; then, there will be hearings for the civil plaintiffs’ lawyers (February the 20th and 27th) and those for the defence lawyers (March the 10th and 29th).

PHOTO: Public Prosecutor Dr Mariagiovanna Compare

Colace wants to make the judges (Chief Justice Dr Gianfranco Pezone, with magistrate Dr Manuela Massino and the six members of the Jury – giudici popolari –) understand that ‘whatever the outcome, this trial is a page of history for workers and members of the community not only in Casale, but in all the world’.

The estimate is that mesotheliomas worldwide are in the order of magnitude of 50,000 to 100,000 a year.

Colace speaks of a massacre: ‘They say it was caused by asbestos. No,’ he points out, ‘this is a man-made massacre, and it is the macabre symbol of a certain kind of entrepreneurship that has the nature of colonialism’. Then, with his gaze fixed on the court: ‘We believe there is evidence that Stephan Schmidheiny is responsible for these deaths. And we propose to explain why’.

INDICTMENT IN 4 PARTS

The indictment is divided into four sections: 1) the conduct (under what conditions asbestos was used and treated); 2) the event (the demonstration that all 392 were deaths due to mesothelioma); 3) the causal relationship (how exposure to asbestos in the decade 1976-1986, when the defendant owned and managed Eternit, affected those deaths); 4) the subjective element, i.e. the analysis of Schmidheiny’s attitude: “Did he know and accept that all this was happening or was he just careless? We are confident that we can prove conduct amounting to wilful misconduct,” said the prosecutor.

DIFFICULT TRIAL

Scientific and legal problems have to be faced and solved.

PP Colace dwells on the first of the two sections: ‘Technical experts are the bearers of science in the courtroom, but they must be neither accusers nor defenders, because judges need the support of science, not personal points of view. He adds ‘consultants can do whatever they want, but if they do not stick to science, they are not credible’. In the prosecutor’s opinion, ‘the defence experts, on the other hand, demonstrated an excess of defensive zeal that made a mockery of logic’. And again: ‘We have often witnessed a juxtaposition between science and eccentric, sometimes personal, points of view, always and only aimed at challenging the scientific studies set out by the prosecution’s expert witnesses who, instead, made these studies not for the trial, but before, observing and analysing phenomena according to scientific criteria. Yet, in this courtroom, they were attacked as if they had got everything wrong…’.

According to the reconstruction of the defence experts, in fact, a picture emerged in which ‘between 1976 and 1986 [the period of the defendant’s management] there was almost no asbestos in the plant, everything was under control, and that outside the factory the only fibres spread were those of the beatings [pulverized asbestos waste] dust (and who had ever distributed it? Ah, well, it had been distributed by those who were in charge of Eternit before Schmidheiny!), and also that in that decade it was not Schmidheiny himself who actually managed the company but his managers, and that almost all those deaths would not even have been mesothelioma deaths… perhaps the Casale doctors exaggerated in making the diagnoses… But then,’ the prosecutor’s question: ‘why are we here?’

“WHY ARE WE HERE?”

‘Because the picture is different,’ declares Colace, ‘in Casale there has been, and will still be for years, an epidemic of mesotheliomas. And there have been no overestimations or medical errors: Casale is not a martyr town of malpractice, but a martyr town of asbestos’.

What gives no peace of mind is that ‘that epidemic could have been avoided, or at least the impact of the massacre could have been limited’.

Colace traces the history of Eternit, the transition from the predominantly Belgian management (of the Emsens/de Cartier family) to the Swiss one (of the Schmidheiny family); he recalls that the products (in Casale, slabs and pipes) were made from a mixture of cement and asbestos; that asbestos raw material was used in the production cycle in massive quantities. Both white asbestos (chrysotile) and blue asbestos (crocidolite, the most dangerous) were used; the latter in a proportion of 10% of total use (over 1600 bags of 50 kg each per day).

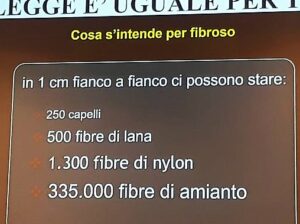

PHOTO: The table with some data on the quantities of asbestos used as raw material in the production of manufactured goods

‘PRECAUTIONS NOT RESPECTED’

According to the prosecution, in a production sector that is so delicate for the health of workers and the environment, ‘none of the safety precautions at work (moreover, already indicated in Presidential Decree 303 of 1956) were respected’.

What was the situation in the factory? ‘Catastrophic’ defined one senior manager in 1973. And later? Another manager, in 1975, described it as ‘a dirty, dusty environment, disorganised in the planning of maintenance and the management of vacuum systems’. And then? ‘In 1976, Klaus Robock, a scientist working for the Eternit group, in an internal memo, following an inspection at Casale, notes defects and problems “on which action must be taken”‘.

How does one act

The defence, through its consultants, has asserted (and it will certainly be an argument that will be taken up in the haranguing) that Stephan Schmidheiny invested a lot of money in protective measures at Italian Eternit. Colace is sceptical; ‘in the meantime, at each trial the figures indicated by the defence continue to increase’; furthermore, ‘our consultant has reconstructed the entity and destination of those flows; well, they served more to cover losses than to invest in safety’. Not that there was no investment at all, e.g. certainly in new plants and in the transition from dry to wet processing; but the quantification of specific investments for safety, reconstructed by the prosecution’s consultant, comes to ‘4 billion lire, spent over a ten-year period and spread among all the Italian Eternit plants’. An amount far less than that indicated by the defence counsels.

ASBESTOS BUSINESS UNDER ATTACK

In the 1970s, the asbestos industry was beginning to feel the breath on its neck. In 1964, the scientist Irving Selikoff, at the International Symposium of the New York Academy of Sciences, had sounded the alarm (not the first, by the way) by clearly pointing out the causal link between asbestos and mesothelioma. Asbestos causes mesothelioma, and people die of this malignant cancer; and it does not only affect workers in the industry, but also those who breathe in the fibres released into the air. Reaction of the asbestos industry? Selikoff is to be ignored, his name should not even be mentioned.

The American company Johns-Manville, by the way, had been severely weakened by the stratospheric compensation payments to numerous asbestos victims it had been forced to pay (it went bankrupt in 1982). Workers, trade unionists, journalists, doctors, politicians began to ask questions, too many questions.

So what? ‘The entrepreneur makes a choice: he favours the business and defends himself against the attacks on his business’. And how? Colace recalls the Neuss conference, in 1976, chaired by ‘Schmidheiny in person’, whose objective was as follows: ‘Ensuring the asbestos-cement industry can exist by means of an optimal organisation of labour and environmental protection following internal regulations’, where ‘optimal’, one reads in the minutes of the meeting attended by Eternit’s top executives, equals (=) ‘maximum protection with minimum economic means’.

And what about those who reacted? Those who rebelled (perhaps not so rationally because they are exasperated) were fired.

PHOTO: The above is an excerpt from a communiqué of the labour works council, dated 18/11/1976, entitled ‘Grave provocation’. The text: ‘He was fired on the spot for vigorously protesting against a situation that had been dragging on for a long time. For months the works council had been reporting the spread of dust in the tube department due to inadequate equipment and its inefficiency due to lack of maintenance. It is understandable that at a certain point one loses patience and even goes so far as to say a few words of exasperation between (…) following a cloud of dust that had once again invaded the mixing area of the department. The measure seems all the more serious when one considers that Eternit is a factory where people still fall ill and die of asbestosis and cancer’.

And to whom does he insist? The placebo explanation of ‘Casale 3’ is given, concerning the project to build a new and safe factory in the industrial area on the outskirts of Casale. Riccardo Coppo (the mayor who, in 1987, had signed the famous ordinance banning asbestos in Casale) testified at the Eternit Maxitrial in 2011: ‘At a certain point we realised that they were pulling our leg’ and wrote a letter to Eternit’s majority shareholder to inform him that he was ‘strongly concerned about the decline in employment in the factory, the serious degradation of the plant, but above all about the serious consequences of asbestos processing on the health of workers and citizens’. The letter is dated 24 September 1985. The majority shareholder was Stephan Schmidheiny.

The public prosecutor then refers to Auls76, the ‘manual of disinformation’ he calls it, in which various hypotheses of critical circumstances are listed in detail with the relative answers that had to be given depending on who was asking questions about asbestos (precisely workers, plant neighbours, trade unionists, journalists, politicians and so on), and it is suggested that the German legislation, which is less restrictive than the dust limits indicated by OSHA (the American agency that deals with safety at work), should be used as a reference.

PHOTO: “(…) Since this defamation can endanger the existence of our industry, we must react decisively and we must fight back with all our means.”

“Schmidheiny differentiated the type of information: that to be given to top management, clear about the real risks of asbestos, and that for workers, sweetened, confused”. In one (‘the only’) communication directed to workers, it is written: ‘Asbestos is not dangerous at all: manual contact with it does not cause any damage. Instead, there is smoke that …

PHOTO: The misleading communication given to workers about the risk of asbestos went on:

“(…) eliminate or at least reduce smoking as much as possible. The harmfulness of smoking in itself is well known (…) and it should be borne in mind that the smoking habit can substantially raise the danger of damage to health in conjunction with other harmful factors” [No reference is made to asbestos]. Asbestos, on the other hand, on contact ‘is not dangerous (…), unlike other substances or products ‘whose mere physical contact may produce damage (…): radioactive substances, certain chemicals and the like’.

WAS THERE OR WASN’T THERE DUST?

Prosecutor Colace recalls testimonies (including those of trade unionists Nicola Pondrano and Bruno Pesce, and of workers), documents, inspections (of the Labour Inspectorate, at last), expert reports attesting to the presence of a ubiquitous dustiness, widespread in all the spaces of the factory.

On the other hand, the defence consultants reconstructed a different situation, which the public prosecutor stigmatises as follows: ‘They want us to believe that the factory was as clean as the operating room of a hospital! They have depicted an unrealistic situation, emphasising some data and keeping others silent’.

He showed two photographs on the screen: one is a still from a Luce film showing the working environment between the years 1928 and 1932; the other is an interior view of the factory when it was closed and abandoned in 1986. He addresses the judges: ‘Would you take your children to play there?

PHOTO: Among other things, the works council, in 1983, recalled a series of unfulfilled requests and urged action that had been promised and ignored, including prescriptions issued by the Labour Inspectorate on which the company, years later, was still in default.

And yet, INAIL had become convinced that the Casale plant was virtuous, with dust perfectly below the legal limits, so much so that it had exempted the company from paying the ‘surcharge’ related to the risks of asbestos-related diseases. The consequence was that workers were no longer entitled to the so-called ‘transition annuity’, which allowed them to retire a year early. The trade unionists Pondrano and Pesce mobilised, lawsuits were brought against INAIL before the labour judge, and there the issue of the surcharge no longer paid by the company was discovered, on the grounds that the environmental conditions had improved and the risk of falling ill with asbestosis (a dose-dependent, asbestos-related disease) had been reduced. Judge Giorgio Reposo was faced with the dilemma: ‘But is there dust inside the factory or not? The answer was given by consultant Michele Salvini, a university professor from Pavia, who found the dust, and how right he was; where? Where it had not been thoroughly cleaned in anticipation of the inspection. Incidentally, all the cases for the extra annuity due to significant exposure that went to court were all won by the workers.

Colace insisted: ‘Asbestos dust was widespread inside the plant and outside’.

He lists monitoring results and shows photographs: the suction fans positioned on a wall of the factory that threw out the dust without filtering; the former Piemontese area of the waste crushing with a bulldozer under the open sky; the absence of internal laundries to prevent the workers and female workers from going home in their work clothes (“stopping to buy bread, to pick up their children from school and to hold them in their arms with all those white specks of dust in their hair…. “); the transport by truck, along the streets of the city, of the sacks containing the raw material arriving at the railway station and the finished products transferred to the warehouses in Piazza d’Armi; the dumping of waste water containing asbestos on the right bank of the Po: here they formed a very thick crust, the famous ‘spiaggetta’, a Sunday destination for many families who considered it their ‘Riviera’ on the river.

PHOTO: “As far as suspended substances are concerned, it can be assumed that their output (…) was of the order of 20 tons/week dry. The right bank of the Po where the plant’s general open drainage channel enters has been visibly deformed over the years, creating a peninsula that narrows the riverbed”.

PHOTO: The ‘spiaggetta’ is indicated with a blue outline

PHOTO:The ‘spiaggetta’: a photo taken in 1990 by Stefano Silvestri, one of the Prosecutor’s expert witnesses (from his report)

And, on the left bank of the Po, there was the Bagna dump. Enrico Bagna was the operator who had the contract with Eternit to take away and dispose of scraps and waste from the plant, including large quantities of powder.

THE DEFENCE

“In 1979, Eternit sent a warning to Bagna so that he would no longer sell the powder to citizens who used it for battens (of sports fields, courtyards, roads…) and as an insulating material in attics. ‘Meanwhile,’ the public prosecutor explains, ‘the notice shows that the distribution of dust had not been banned with the beginning of Schmidheiny’s management, in 1976, contrary to what the defence consultants said about the fact that the dust from the “improper uses” in the city had been sold by those who had managed Eternit before Stephan Schmidheiny. Moreover, if Bagna is forbidden to hand it over it is because it is known to be very dangerous… it contains crocidolite among other things… And what is done? Bagna is warned, but the population is kept ignorant instead of being warned of the grave danger!’ And that’s not all: the poor thing, taken away as waste and discarded by the factory, even when it was no longer given to the population, continued to be dumped, ‘at least until 1984’, in the dump on the left bank of the Po: ‘Under the open sky, free to disperse into the air…’ the public prosecutor remarks.

WHAT DOES ASBESTOS DO?

How does asbestos behave? Says Colace: ‘We have caught contradictions between the defence consultants: those who maintain that inside the plant the dust falls and settles around the workstation without dispersing; and those who, referring instead to the outside environment, affirm that the fibres of the dust and the beatings spread widely’. What is the issue? ‘What is good to say for the inside of the factory is not good for the outside?’ And then he doesn’t like the comparison between the intensity of the pollution produced by dust and beatings and that of the factory and the crushing area: are they really comparable? Is the incidence of fibres from the work sites really equal (or even lower, according to the defence expert witness) to that of the so-called ‘improper uses’? “Are we to believe,” the prosecutor asked, “that the asbestos pollution problems at Casale originated mostly from those ‘little holes’ between one tile and another on the roofs, as a defence consultant claimed? And the broken tile, then… a fall in style that I would not have expected from a university professor!’ He was referring to the fact that one of the experts had shown a photograph of a broken tile as a concrete example, according to his thesis, of a damaged roof and the possible leakage of fibres from the underlying insulation. Only that that reconstruction was unreal; in fact, the Arpa technicians who had taken that picture had explained that they themselves had been forced to remove the tile in order to be able to position the instrument needed to carry out the sampling.

WHAT REMAINS?

What is left, now, after 80 years of activity (‘the last surge in production was in 1981, with the conspicuous sale of artefacts for reconstruction after the earthquake in Irpinia’) and after the factory has ceased operations and been abandoned (and then reclaimed with public money from the community)?

“What remains on the territory?’ The public prosecutor spoke for four hours. It is difficult to summarise and make understood such a complex tragedy using simple words. Before he sits down, he looks at the judges one by one and gives an answer: ‘What remains? The 392 cases of death from mesothelioma remain’.

THE DEATHS REMAIN

‘In this trial there are 392 victims,’ points out public prosecutor Mariagiovanna Compare, ‘but it is only a selection of a much higher number.

In total, at least 3,000 deaths are estimated in Casale and the surrounding area. The current increase is around fifty new cases a year. Some time ago, the mayor Riccardo Coppo said: ‘Here you do not have an immediate perception of the scale of the tragedy, because it is a slow and continuous trickle.

Men and women, younger and younger, are leaving, one by one, in silence, without noise, sadly and with resignation, because, as the public prosecutor reiterated, ‘every diagnosis of mesothelioma is a death sentence’.

Yet, ‘the diagnoses were questioned by the defence consultants: according to them, without recourse to the latest immunohistochemical markers, one cannot be certain that they were mesotheliomas and not instead metastases of other primary tumours’.

Compare endorses the scientific arguments of the prosecution’s consultants and the civil parties: ‘It is not true that diagnosis cannot be made without immunohistochemistry, and it is not true that older diagnoses are to be thrown out’.

Meanwhile, ‘there is no specific marker for mesothelioma, but rather markers, more or less sensitive, indicated by international guidelines’.

In any case, the public prosecutor points out, ‘it is always a multidisciplinary diagnosis, in which various types of investigations are involved, and it is necessary that a good pathologist interprets the results of the investigations’.

Regarding the insinuation that the doctors at Casale may have exaggerated with their diagnoses without investigating whether or not the mesotheliomas were primary tumours, Ms. Compare replies that many of them were not made at Casale, but in hospitals in other cities or other regions, even in the Lombardy centre where the defence anatomist Massimo Roncalli practised (‘and his colleagues had no doubts about the certainty of that diagnosis!’).

He goes through, card by card, name by name: life, habits, passions and death of many of the victims listed in the indictment. He insists: ‘Every increase in exposure increases the risk of falling ill and this increase also results in an anticipation of death.

‘They are all 392 mesotheliomas,’ concludes Prosecutor Mariagiovanna Compare. No doubt we have. And – addressing the judges – no doubt you can have’.

PHOTO: The Court of Assizes in Novara, Monday 30 January, during the closing speeches

The Prosecutors continue on Friday, 10 February.

Grazie per la documentazione accurata e puntuale…tra gli uomini e donne che se ne sono andati in silenzio per il mesotelioma il 28 novembre scorso c’è anche mia cognata Carla..

Dopo aver letto attentamente il tuo dettaglio resoconto una frase resta scolpita nell’anima: “restano i morti”.

Fiumi di parole fortunatamente da te scritte in modo chiaro e preciso. Parole che sono state procedure da fatti gravissimi il decesso dei nostri cari parenti amici conoscenti. Speriamo che sia ORIGINALE anche la sentenza che faccia definitivamente giustizia che rimarrà sempre incompleta per coloro che non ci sono più.

Non riesco a pensare come i difensori dell’accusa riescano a chiudere occhi e orecchie per non vedere una strage unica e ORIGINALE come questa! Lascia senza parole una tale durezza di cuore. Avranno forse ricevuto la classica “mazzetta” per dirottare la realtà della storia e dei fatti verso menzogne e falsità cammuffate con argomentazioni scientifiche? Mi auguro allora che anche questi tali (che fatico a definire persone) possano sentirsi dire da un medico oncologo: “occorre fare ulteriori accertamenti perchè si potrabbe dare la presenza di un meso”…! Chissà se anche il quel caso sarebbero ugualmente pronti a negare la verità di una malattia che verrebbe a colpire loro stessi!

Tante grazie Silvana !

Sempre puntuale, sempre un grande lavoro ed importante contributo per recuperare informazione e verità su questa enorme tragedia.

Grazie Silvana …la tua forza è I tuoi resoconti ci accrescono di conoscenza e memoria…anche tanto dolore e sofferenza..nel vedere dalle posizioni di difesa che tutto viene utilizzato per legittimare gli interessi di mercato e di profitto…e orribile vedere che ormai anche in altri ambiti…stragi…e tutto avviene per il forte valore del denaro…io non perdono. ..queste culture…grazie e ti abbraccio