SILVANA MOSSANO

Reportage Eternit Bis, udienza del 17 settembre 2021

«Quando sono arrivato a Casale, nel 1979, e ho assunto l’incarico di segretario della Camera del lavoro, ebbi subito un occhio di riguardo verso l’Eternit, che era la più grande azienda forse addirittura della provincia. Molti lavoratori si ammalavano di asbestosi che non veniva considerata particolarmente rilevante perché non è un tumore. Ma lo sapete come si muore di asbestosi? Soffocati» scandisce Bruno Pesce. All’allora giovane sindacalista, ma già con anni di esperienza nel Valenzano, fu affidato il compito di avviare e organizzare il nuovo gruppo dirigente della Camera del lavoro casalese, nella storica sede, fino a pochi anni fa, in piazza Castello. «Ne morirono decine e decine, soffocati» ha detto ieri mattina, venerdì 17 settembre, alla Corte d’Assise di Novara, presieduta da Gianfranco Pezzone (affiancato dal giudice Manuela Massino più i giudici popolari), che si trova a processare Stephan Schmidheiny, l’ultimo patron in vita dell’Eternit. L’imputato, difeso da Astolfo di Amato e Guido Carlo Alleva, deve rispondere dell’omicidio volontario, con dolo eventuale, di 392 persone, morte per mesotelioma, il cancro causato dall’amianto.

MESOTELIOMA, MALATTIA PROFESSIONALE

«Di mesotelioma – ha spiegato Pesce – alla fine degli anni Settanta si cominciava a parlare, ma alcuni non sapevano neppure pronunciare la parola». Rispondendo alle domande del pm Mariagiovanna Compare (che, con Gianfranco Colace, sostiene la pubblica accusa), il testimone ha ripercorso l’attività sindacale riguardante l’Eternit che, tra l’apertura a inizio Novecento e la chiusura nel 1986, ha dato lavoro a migliaia di dipendenti. «Si facevano molte cause per il riconoscimento della malattia professionale che, fino a un certo punto, era principalmente l’asbestosi». E il mesotelioma no? «Solo nel 1986 l’Inail riconobbe per la prima volta il mesotelioma come malattia professionale senza che fosse “mediato” dall’asbestosi: prima, se non c’era una precedente diagnosi di asbestosi, il solo mesotelioma non veniva considerato malattia professionale».

Ma andiamo per gradi. Riprendiamo dalla fine degli anni Settanta. Di quelli precedenti, delle battaglie per la salubrità ambientale dentro la fabbrica affacciata su via Oggero, nel quartiere Ronzone, aveva raccontato alla passata udienza Nicola Pondrano, che lavorava dentro ed era nel consiglio di fabbrica prima di diventare dirigente sindacale.

PESCE E PONDRANO

Era inevitabile che i due – Pesce e Pondrano – si incontrassero. Uno di quegli incontri che il destino, con giri imperscrutabili, colloca in un preciso momento perché funzionale allo scorrimento della storia.

«Sapevo che Pondrano era nella commissione ambiente del consiglio di fabbrica e lo distaccai al sindacato. C’era simbiosi e collaborazione strettissima tra me e lui. Promuovemmo centinaia di cause per il riconoscimento delle malattie professionali. La nostra fu una dedizione totale».

LE CAUSE ALL’INAIL

Si arriva all’81, «sì, quando scoprimmo che l’Eternit aveva convinto l’Inail che nella fabbrica non c’era più amianto e quindi non era più tenuta a pagare il premio supplementare. Diciamolo: l’azienda risparmiava qualche miliardino di lire non versandolo all’Inail». E questo che ricaduta aveva? «Che ai lavoratori non veniva più riconosciuta la cosiddetta “rendita di passaggio”, cioè la possibilità di andare in pensione in anticipo per evitare l’aggravamento dell’asbestosi, beneficiando di un’annualità di stipendio. Ma noi – ha detto il testimone Pesce, con lo stesso stupore e sgomento che lui e Pondrano devono aver provato allora – cademmo dalle nuvole! Eravamo strabiliati». Da qui i ricorsi al giudice del lavoro promossi contro l’Inail («in realtà noi ce l’avevamo con l’Eternit, ma tecnicamente le cause dovevano essere fatte contro l’Istituto Infortuni sul Lavoro») che furono vinti praticamente tutti. «Ricordo quando davanti al pretore Giorgio Reposo, a Casale, andò a testimoniare Giovanni Demichelis, era ormai gravissimo, fu portato in aula su una barella e il giudice dovette scendere dallo scranno e avvicinare l’orecchio alle sue labbra per capirne le parole. Ma era deciso Demichelis: “Voglio testimoniare” insistette». Morì d’amianto entro la fine di quella settimana.

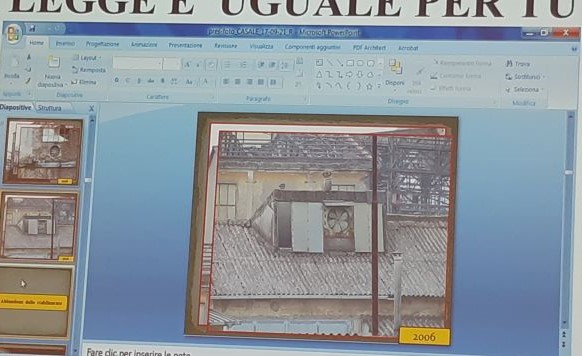

I procedimenti per le cosiddette «rendite di passaggio» furono quelli in cui il pretore nominò come consulente il professor Michele Salvini, dell’Università di Pavia. «Sì, lui, che salì sulla scaletta e trovò la polvere d’amianto, altro che non ce n’era più in fabbrica! Mica si era fidato che in tutti i reparti, prima della sua ispezione, fosse stato fatto un lavorone di pulizia eccezionale: i reparti tirati a lucido, ah, in quello erano stati bravissimi». Pesce abbozza un sorriso: «Scusate – dice rivolto ai giudici – a volte io uso l’ironia per non bestemmiare».

LA POLVERE SULLA FONTANA

Il teste ha ricordato che il professor Salvini, di propria iniziativa, era poi andato a ispezionare altre zone della città, fuori dalla fabbrica, ad esempio «la fontana in piazza Dante. Di amianto ce n’era anche lì».

E come mai la polvere era anche fuori dalla fabbrica? Pesce ha ricordato qualche esempio: «La frantumazione degli scarti di manufatti che avveniva sulla piattaforma nell’area cosiddetta Ex Piemontese, quasi di fronte allo stabilimento, schiacciati a cielo aperto con un cingolato munito di benna: i materiali triturati venivano trasferiti con un motocarro nello stabilimento e convogliati nel mulino Hazemag. Un operaio, Angelo Gnocco, mi raccontò che si era inaugurato questo sistema dagli ultimi anni Settanta fino alla chiusura della fabbrica, anche se alla fine la produzione era molto diminuita. E i ventoloni… ecco proprio quelli – ha detto Pesce indicandoli, quando i pm hanno proiettato una foto storica sullo schermo – …aspiravano l’aria insalubre da dentro e la buttavano fuori, e si spingeva verso la città, e la respiravano tutti. E poi c’erano i camion che andavano e venivano: portavano i sacchi d’amianto dalla stazione allo stabilimento passando per le vie cittadine e, viceversa, trasportavano i manufatti finiti, tubi e lastre, dalla fabbrica alla stazione: non è mica una scoperta! Scoperti, caso mai, erano i camion». E c’era pure il polverino che le persone andavano a prendere in fabbrica. Si pagava?, vuole sapere la pm Compare. «Qualcuno diceva di no, altri dicevano che davano un “obolo”, ma poco» e finiva «nei sottotetti, nei cortili, nei campetti sportivi, anche in qualche sagrato delle chiese». E la «spiaggetta»? «Ah, quella, le “Canarie del Monferrato” la chiamavano, un crostone che si era formato sul Po con i materiali contenenti negli scarichi reflui della fabbrica. Le famiglie ci andavano volentieri d’estate, anche a fare i picnic. Dicevano che la spiaggetta era bella e liscia».

«QUELLA E’ LA PORTA»

E di fronte a tutto questo come si reagiva? «La busta paga era importante e irrinunciabile: in quegli anni le battaglie ambientali dovevano coniugarsi con la prioritaria difesa del posto di lavoro. E i cambi di mansione non erano considerati. Ricordo Giampaolo Bernardi, faceva il manutentore. Andò a parlare con il capo del personale Carlo Oppezzo e gli disse: “Mi cambi mansione, magari non subito, magari tra un anno, ma mi assegni un incarico meno pericoloso, sa, ho tre bambini, vorrei vederli crescere”. Oppezzo, senza alzare gli occhi dalla scrivania, disse semplicemente: “Bernardi, lei sa dov’è la porta”. Bernardi è morto di mesotelioma. E poi ricordo Anna Scaiola, ha lavorato 31 anni all’Eternit, aveva un’ora per l’allattamento della sua bambina, e mica aveva tempo di togliersela la blusa quando attaccava la figlia al seno».

LO STABILIMENTO MAI FATTO

Altro ricordo: «Nell’81, mi fermò davanti alla Camera del lavoro un insegnante, Patrucco di cognome, “ma cosa aspettate a chiudere l’Eternit?” mi domandò, i suoi genitori erano morti di mesotelioma. “Vedi, gli dissi, se dico di chiudere la fabbrica lascia il tempo che trova, la gente vuole il lavoro”. Noi, allora, pensavamo alla riconversione». Si era sentito dire di uno stabilimento nuovo in strada Valenza: «Come sindacato, pensavamo di batterci perché fossero usate fibre alternative all’amianto, ma poi, di quel trasferimento in strada Valenza, non se ne parlò più».

Dopo il fallimento dell’Eternit dell’86, «la Safe, cioè l’Eternit francese, nell’87 propose di riaprire, assumendo tra i 50 e 70 lavoratori dei 350 che erano rimasti a casa dopo la chiusura, ma avrebbe continuato a lavorare l’amianto. Ci fu la lettera di 110 medici che scongiurarono una simile evenienza e, a dicembre 1987, l’allora sindaco Riccardo Coppo firmò la famosa ordinanza che vietava l’uso dell’amianto nel comune di Casale».

«Nell’87, cominciammo le cause per ottenere, dal fallimento, risarcimenti per chi si ammalava e moriva. Ci fu un processo penale, a Casale, nel ’93, ma i tempi lunghi portarono alla prescrizione, tranne che per un caso».

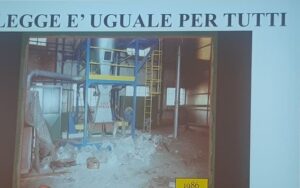

FABBRICA ABBANDONATA

Lo stabilimento inattivo, intanto, rimase esposto alle intemperie: «Abbandonato ai quattro venti, con tonnellate di amianto dentro». La bonifica l’ha fatta, poi, negli anni a venire l’ente pubblico, dopo un braccio di ferro con la curatela fallimentare per acquisire lo stabilimento allo scopo, appunto, di bonificarlo a regola d’arte e demolirlo senza ulteriori rischi per la popolazione.

Ci volle molto tempo, fu un percorso complesso e accidentato, tra gare d’appalto internazionali, assegnazioni, ricorsi e altri intoppi conflittuali anche durante l’intervento.

«Da Schmidheiny o da qualche società a lui collegata non arrivò mai un segnale di disponibilità a contribuire alla bonifica?» si è informata la pm Compare. «Noo, no. I primi soldi per le bonifiche arrivarono dalla Regione, quando era assessore il casalese Paolo Ferraris». Il suo nome, tra l’altro, è tra quelli delle 392 vittime di mesotelioma elencate nel processo Eternit Bis.

«Sempre dalla Regione arrivarono le risorse stanziate dall’allora assessore Sante Baiardi per la prima indagine epidemiologica avviata e condotta da Benedetto Terracini e dai suoi collaboratori tra l’83 e l’87. Appurò che, nel Casalese, c’erano centinaia di morti d’amianto oltre la media».

SPESE PER BONIFICA E SANITA’

Furono sempre le istituzioni pubbliche a finanziare le bonifiche di edifici e ritrovamenti di polverino in tutto il territorio.

I soldi pubblici spesi per questo scopo, dal 1996 a oggi, nel «Sito di interesse nazionale di Casale» ammontano a 120 milioni di euro: ne ha dato puntuale resoconto ieri a Novara l’attuale presidente della Regione Piemonte Alberto Cirio, mentre i costi a carico del sistema sanitario, e quindi della collettività, per le cure necessarie a ogni singolo caso ammontano a 33 mila euro per il percorso diagnostico-terapeutico, 25 mila euro per costi assicurativi e 200 mila euro per le perdite legate alla mancata attività lavorativa».

Insiste la pm: qualcuno del gruppo Eternit si è fatto avanti per contribuire? «No, non mi risulta nessun contatto» ha affermato Cirio.

AFLED E POI AFEVA

Pesce ha poi ricordato la fondazione dell’Afled (Associazione famigliari del lavoratori Eternit deceduti), nel 1988, che divenne Afeva (Associazione famigliari e vittime amianto) nel 2000, perché ormai era chiaro che a morire d’amianto erano anche i cittadini (e ora sono la quasi totalità, perché «i lavoratori Eternit sono quasi tutti morti» ha ricordato il teste).

«Se riuscissimo a contarli tutti, arriviamo a non meno di tremila morti tra mesoteliomi, asbestosi, cancro al polmone» ha detto Pesce.

LA STORIA DEL «PICA»

Cittadini che non hanno mai avuto a che fare con l’Eternit, come Piercarlo Busto, bancario, figlio di un insegnante di liceo e di una casalinga, vissuto in una zona piuttosto centrale della città. Di lui ha parlato la sorella Giuliana, attuale presidente dell’Afeva: «Sportivo, non fumava, salutista al cento percento. Andava ad allenarsi sull’argine del Po, attiguo all’Eternit. Un giorno, durante l’allenamento, sentì un dolore al petto; poi un po’ di tosse, febbriciattola, stanchezza. Fece una lastra e gli trovarono l’acqua nei polmoni. Solo un po’ dopo, a Pavia, il professor Moncalvo, appena seppe che veniva da Casale, la diagnosi la fece subito: mesotelioma». Giuliana Busto ricorda nel dettaglio quei giorni: «L’avevo mai sentita ‘sta parola. Consultai un’enciclopedia medica, dove si diceva che era il cancro correlato all’amianto, così mi dissi “ma si sono sbagliati, il Pica non ha mai toccato l’amianto, lavora in banca lui”. Morì il 23 dicembre, dopo cinque mesi di dolori atroci, e noi, la vigilia di Natale, invece di andare a scegliere i regali, andammo a scegliere la bara». Sul manifesto funebre scrissero: «Ucciso dal mesotelioma». «Fu uno schiaffo alla città, una scossa, si cominciò a far strada la consapevolezza che l’amianto non risparmia nessuno».

Giuliana Busto, dopo quel lutto, contattò il sindacato, ed entrò a far parte dell’Afled divenuta successivamente Afeva, ne fu attivista convinta e dal 2016 ne è la presidente; prima di lei, Romana Blasotti Pavesi e poi Giuseppe Manfredi, con il suo vice Giovanni Cappa, entrambi già morti per mesotelioma.

L’associazione è divenuta punto di riferimento per i malati e i loro famigliari, paladina di tutte le battaglie sociali, sanitarie e propulsive sul fronte della ricerca di una cura, ambientali per le bonifiche e giudiziarie nei vari processi, insieme alle organizzazioni sindacali Cgil Cisl e Uil e alle istituzioni («il Comune si è sempre schierato con noi» ha detto Pesce; «la Regione farà tutto quello che è in suo potere perché i responsabili di queste migliaia di morti paghino, perché la vita è un bene che non può non ricevere giustizia» ha assicurato Cirio).

L’attivismo mobilitò le coscienze, divenne condiviso ed esteso, perché il mesotelioma non risparmia nessuno, anzi ha alzato il tiro. Si è passati da una ventina di nuovi malati all’anno (anni Ottanta) a una cinquantina attuali (il 2021, ha detto di recente l’oncologa Daniela Degiovanni, è il primo anno in cui pare di cogliere l’avvio della fase discendente nel numero di nuovi casi di malattia. Forse il picco è stato raggiunto e si comincia a scendere?).

«AVEVAMO UNA SPIA»

Via via, chiunque avesse bisogno e chiunque volesse collaborare, trovava aperta la porta dell’associazione. «Anche la spia. Ne posso parlare?» ha domandato cautamente il testimone Pesce. Dica, dica, incalzano i pm.

«Una certa Cristina Bruno, era commercialista e giornalista free lance, per un certo periodo era stata anche addetta stampa della nostra Flm. Era insistente, petulante. Io ero il segretario della Camera del lavoro e mi toccava sopportarla più di tutti. “Cosa fate? Quando vengono gli avvocati? Come impostate le cause? Vorrei partecipare alle vostre riunioni, io sono dei vostri”. Asfissiante, ma ben lontano da noi il pensiero che fosse un’informatrice, una “antenna” era definita, al soldo di Schmidheiny. Vennero fuori le fatture che le erano state pagate per le prestazioni informative dall’84 in poi per il tramite dell’agenzia di pubbliche relazioni Bellodi di Milano. A quanto so, è poi stata radiata dall’Albo dei giornalisti».

LE TRANSAZIONI CON I CITTADINI

Prima che iniziasse il maxiprocesso Eternit Uno a Torino, gli emissari di Schmidheiny contattarono gli avvocati di Afeva per proporre una transazione risarcitoria: 30 mila euro ai famigliari delle vittime che avessero, in cambio, rinunciato a costituirsi parte civile; a quella cifra, furono aggiunti contestualmente 20 mila euro depositati su un conto specifico destinato alla ricerca medico-scientifica. «Ma anche l’associazione Afeva riceveva una somma per ogni offerta individuale?» ha domandato l’avvocato Di Amato, difensore di Schmidheiny. Pesce ha risposto: «Sì, ci è stato riconosciuto qualcosa per le pratiche amministrative che svolgevamo tra i cittadini e la società di Schmidheiny per seguire i passaggi di queste transazioni. Transazioni che mi pare un po’ esagerato chiamare risarcimento… 30 mila euro per la vita di una persona…. E i soldi assegnati ad Afeva per queste pratiche sono sempre stati spesi per l’attività a sostegno della battaglia contro l’amianto». Rievoca i giorni di quella proposta: «Non ci dormimmo per alcune notti – ha ricordato il testimone -: per noi era importante fare il processo che stava per iniziare dopo le centinaia di esposti che avevamo presentato alla procura di Torino nel 2004 e portare molte parti civili: questo era, ed è, il nostro obbiettivo di giustizia. Ma ci era stato detto chiaramente, dagli emissari di Schmidheiny che contattarono i nostri legali, che, se quella mediazione non l’avessimo fatta come associazione, la società l’avrebbe attuata ugualmente con un proprio incaricato. Beh, alla nostra gente preferivamo spiegare noi qual era la situazione. C’erano vedove che, per necessità, hanno accettato piangendo…».

L’UDIENZA DI LUNEDì 20

Lunedì prossima udienza a Novara: verranno ascoltati Piercarla Coggiola, dirigente dell’Ufficio Ambiente Ecologia del Comune di Casale, il sindaco attuale Federico Riboldi e Giovanna Patrucco, figlia della panettiera del Ronzone morta di mesotelioma

Nella foto in apertura, il dettaglio dei «ventoloni» che buttavano fuori dalla fabbrica l’aria insalubre

* * *

Traduzione a cura di Vicky Franzinetti

SILVANA MOSSANO

Eternit Bis, 17 September 2021 hearing

“When I arrived in Casale, as Union Secretary in 1979, I immediately focused on Eternit, which was the biggest company in town, perhaps even in the province. Many workers were developing asbestosis, which was not considered particularly relevant at the time because it was not cancer. Do you know how people die of asbestosis? Suffocated,’ says Bruno Pesce. The then young trade unionist, already had years of experience in the Valenzano area[1]. He was entrusted with the task of launching and organising the new leadership of the CGIL Union in Casale, in Piazza Castello, its traditional headquarters and where it was till a few years ago. “Dozens and dozens of them died, suffocated,” he said yesterday morning, Friday 17th of September, at the Court of Assizes of Novara, presided by Chief Justice Gianfranco Pezzone (assisted by Judge Manuela Massino and the Jury – aka as popular judges), which is trying Stephan Schmidheiny, the living owner of Eternit. The defendant, represented by Astolfo di Amato and Guido Carlo Alleva, is accused of voluntary homicide, with possible wilfulness, of 392 people who died of mesothelioma, the cancer caused by asbestos.

MESOTHELIOMA, OCCUPATIONAL DISEASE

“At the end of the 1970s, people began to talk about mesothelioma, but some people did not even know how to pronounce the word,” Pesce explained. Answering questions by Mariagiovanna Compare who is prosecuting the case with Gianfranco Colace, the witness retraced the trade union activity in Eternit which, from the early 1900s to its closure in 1986. The company employed thousands of employees. “Many lawsuits were filed for the occupational diseases which, up to a certain point, was mainly asbestosis”. And not mesothelioma? “It was only in 1986 that INAIL recognised mesothelioma as an occupational disease without it being ‘mediated’ by asbestosis: previously, if there was no previous diagnosis of asbestosis, mesothelioma in itself was not considered an occupational disease.

But let’s take it step by step. Let’s go back to the late 1970s. At the last hearing, Nicola Pondrano, who was an Eternit factory worker and was on the works council before becoming a union leader, told us about the battles for environmental health in the factory overlooking Via Oggero, in the Ronzone district.

PESCE AND PONDRANO

It was inevitable that the two – Pesce and Pondrano – would meet. One of those meetings that fate places in a precise moment because it is changes the story.

“I knew that Pondrano was in the environment committee of the works council and I seconded him to the union. There was a very close symbiosis and collaboration between him and me. We promoted hundreds of cases for the recognition of occupational diseases. We were totally dedicated.

THE INAIL CASES

In 1981, “yes, when we discovered that Eternit had convinced INAIL [2] that there was no more asbestos in the factory and therefore it was no longer required to pay the additional premium to the Workers’ Compensation Fund. Let’s face it: the company saved a few hundred million Euros (billion lirae at the time) by not paying it to INAIL”. And what was the impact of this? “Workers were no longer entitled to the so-called ‘bridging pension for early retirement on medical grounds’ (rendita di passaggio), to avoid their asbestosis getting worse, which corresponded to a year’s salary. We were dumbfounded,” said Pesce, with the same astonishment and dismay that he and Pondrano must have felt at the time. “We were amazed. Hence the appeals to the Industrial Court against Inail (‘actually we had a grudge against Eternit, but technically the cases should have been brought against the Istituto Infortuni sul Lavoro- The Work related Accidents Agency ‘) which were practically all won. “I remember when Giovanni Demichelis went to testify in front of the magistrate Giorgio Reposo in Casale, he was already very seriously ill, he was brought into the courtroom on a stretcher and the judge had to get off the bench and put his ear to his lips to understand his words. But Demichelis was determined: ‘I want to testify,’ he insisted. He died of asbestos by the end of that week.’

The proceedings for the so-called Bridging pension for early retirement on medical grounds ‘ were those court appointed Professor Michele Salvini of Pavia University acted as a consultant. “Yes, he was the one who climbed up the ladder and found asbestos dust – there was none left in the factory! He didn’t trust that all the shop-floors had been cleaned to a high standard before his inspection: the floor had been polished up, and they had been very good at that. Pesce offers a wry smile: “Excuse me,” he tells the judges, “sometimes I use irony to avoid swearing.

THE DUST ON THE FOUNTAIN

The witness recalled that Professor Salvini, on his own initiative, had then gone to inspect other areas of the city, outside the factory, for example ‘the fountain in Piazza Dante. There was asbestos there too’.

And how come the dust was also outside the factory? Pesce recalled a few examples: “The shredding of waste products that took place on the platform in the so-called Ex Piemontese area, almost opposite the factory, crushed in the open air with a caterpillar equipped with a bucket: the shredded materials were transferred to the factory by a truck to the Hazemag mill. One worker, Angelo Gnocco, told me that this system had been in operation from the late Nineteen Seventies until the factory closed down, even though production had decreased considerably in the end. And the fans … that’s exactly what they were,” Pesce said, pointing to them when the prosecutors projected a historical photo on the screen, “they sucked the unhealthy air from inside and threw it out, and it floated into, and everyone breathed it in. And then there were the lorries that came and went: they carried the sacks of asbestos from the station to the factory via the city streets and, vice versa, they transported the finished products, pipes and sheets, from the factory to the station: they were open, no covering. And there was also the dust that people went to the plant to get. Did they pay for it?”, says Ms Compare. “Someone said no, others said that they gave a ‘donation’, but not much” and it ended up lining their attics, courtyards, sports fields, even some churchyards”. And the “little beach”? “Ah, that one, the “Canary Islands of Monferrato” called it, a crust that had formed on the Po with the materials contained in the factory’s waste waters. Families liked to go there in the summer, even for picnics. They said the beach was beautiful and smooth” and white.

“THAT’S THE DOOR”.

And how did people react to all this? “The pay packet was important essential: in those years, environmental battles had to be combined with the priority of defending jobs. Changing jobs in the plant was not an option. I remember Giampaolo Bernardi, who was a maintenance worker. He went to talk to the Head of Personnel Carlo Oppezzo and said: “Change my job, maybe not immediately, maybe in a year, but give me a less dangerous job, you know, I have three children, I would like to see them grow up. Oppezzo, without looking up from his desk, simply said: ‘Bernardi, you know where the door is’. Bernardi died of mesothelioma. And then I remember Anna Scaiola, she worked at Eternit for 31 years, she had an hour to breastfeed her child, and she didn’t have time to take off her overall when she breastfed her daughter”.

THE PLANT THAT WAS NEVER BUILT

Another recollection: “In 1981, I was stopped in front of the Union by a teacher, went by the surname of Patrucco, who said to me, ‘what are you waiting for to close Eternit down? You see,” I told him, “if I campaign to close the factory, it’s no use, people want jobs. We were thinking of converting production. He had heard about a new plant in Strada Valenza: “As a trade union, we thought we would fight for the use of alternative fibres to asbestos, but then, no more was said about the new plant in Strada Valenza”.

After Eternit’s bankruptcy in 1986, “the Company’s ‘safe’, that is the French Eternit, proposed to reopen in 1987, hiring between 50 and 70 workers out of the 350 who had been left home after the closure, but it would have continued to work with asbestos. There was a letter from 110 doctors who averted such an eventuality and, in December 1987, the then mayor Riccardo Coppo signed the famous ordinance banning the use of asbestos in the Municipality of Casale”.

“In 1987, we started the lawsuits to obtain compensation from the bankruptcy for those who became ill and died. There was a criminal trial, in Casale, in 1993, but because of the time, the statute of limitations kicked in, except for one case.

THE PLANT WAS ABANDONED

In the meantime, the idle factory remained there, exposed to all weather conditions: “Left to the four winds, with tons of asbestos inside. In the years that followed, the reclamation was carried out by the public authorities, after a tug-of-war with the bankruptcy trustee to purchase the factory plant in order to clean it up properly and demolish it without further risk to the population.

It took a long time, and was a complex and bumpy ride, with international tenders, assignments, appeals and other hitches.

“Did Schmidheiny or any of the companies linked to him ever give any indication that he was willing to contribute to the clean-up operation? “No, no. The first money for the reclamation came from the Region, when Paolo Ferraris, from Casale, was councillor. His name, by the way, is among the 392 mesothelioma victims listed in the Eternit Bis trial.

“The Region also provided the resources allocated by the then councillor Sante Baiardi for the first epidemiological survey carried out by Benedetto Terracini and his collaborators between 1983 and 1987. He ascertained that, in the Casale area, there were hundreds of above-average asbestos-related deaths”.

REMEDIATION AND HEALTH COSTS

It was always the public authorities that financed the reclamation of buildings and dust throughout the area.

The public money spent for this purpose, from 1996 to the present, in the “Site of National Interest of Casale” amounted to 120 million Euros: the current president of the Piedmont Region, Alberto Cirio, gave a detailed account yesterday in Novara, while the costs borne by the health system, and therefore the community, for the necessary treatment of each case amounted to 33,000 Euros for diagnostic and therapies, 25,000 Euros for insurance costs and 200,000 Euros for losses related to the loss of work.

The prosecutor insists: has anyone from the Eternit group come forward to contribute? “No, I am not aware of any contact,” said Cirio.

AFLED AND THEN AFEVA

Pesce then recalled the founding of Afled (Association of families of deceased Eternit workers) in 1988, which became Afeva (Association of families and victims of asbestos) in 2000, because it was now clear that people were also dying of asbestos (and now they are almost all, because “Eternit workers are almost all dead,” said the witness).

“If we could count them all, there are no fewer than three thousand deaths from mesothelioma, asbestosis and lung cancer,” Pesce said.

‘PICA’ STORY

Members of the community who have never had anything to do with Eternit, such as Piercarlo Busto, a banker, the son of a high school teacher and a housewife, who lived in a fairly central area of the city died too. His sister Giuliana, the current president of Afeva, talked about him: ‘He was a sports man, he didn’t smoke, he was one hundred per cent healthy. He used to train on the Po embankment, next to Eternit. One day, during training, he felt a pain in his chest; then a little cough, fever, tiredness. He had an X-ray and they found water in his lungs. Only a little later, in Pavia, Professor Moncalvo, as soon as he heard that he was from Casale, immediately made the diagnosis: mesothelioma’. Giuliana Busto recalls those days in detail: ‘I had never heard that word. I consulted a medical encyclopaedia, where it said it was cancer related to asbestos, so I said to myself ‘but they’re wrong, Pica has never touched asbestos, he works in a bank’. He died on December the 23rd, after five months of excruciating pain, and on Christmas Eve, instead of going to choose presents, we went to choose the coffin”. On the funeral poster they wrote: “Killed by mesothelioma”. “It was a slap in the face for the city, a shock, the awareness that asbestos spares no one began to make itself felt.

Giuliana Busto contacted the trade union after that tragedy, and joined Afled, which later became Afeva, and was a convinced activist, and has been its president since 2016. She replace Romana Blasotti Pavesi and then Giuseppe Manfredi, with his deputy Giovanni Cappa, both of whom have died of mesothelioma since then.

The association has become a point of reference for patients and their families, a champion of all the social, health and propulsive battles on the front of the search for a cure, environmental remediation and judicial in the various processes, along with trade unions Cgil Cisl and Uil and institutions (“the municipality has always sided with us,” said Pesce; “the Region will do everything in its power to make those responsible for these thousands of deaths pay, because life is an asset that must receive justice,” assured Cirio).

Activism mobilised consciences, became shared and widespread, because mesothelioma spares no one, indeed it has raised its sights. It has gone from around twenty new patients a year (in the 1980s) to around fifty a year at present (2021, oncologist Daniela Degiovanni recently said, is the first year in which we seem to see the start of a downward phase in the number of new cases of the disease. Perhaps the peak has been reached and are we starting to go downhill?).

“WE HAD A SPY AMONG US”

Little by little, anyone in need and anyone who wanted to cooperate found the door of the association open. “Even the spy. Can I talk about it?” asked the witness Pesce cautiously. Say, say, the prosecutors pressed.

“A certain Cristina Bruno, she was a chartered accountant and freelance journalist, and for a certain period she had also been our Flm’s (Metalworkers’ Union) press officer. She was insistent, nagging. I was the secretary of Union and I had to put up with her more than anyone else. “What are you doing? When do the lawyers come? How do you set up the cases? I’d like to attend your meetings, I’m one of you”. She was asphyxiating, but we were far from thinking that she was an informer, an ‘antenna’ as she was called, on Schmidheiny’s payroll. It turned out that she had been paid invoices for information services from 1984 onwards through the Bellodi public relations agency in Milan. As far as I know, she was then struck off the Register of Journalists’.

CASH PAY-OFFS

Before the start of the Eternit Uno maxi-trial in Turin, Schmidheiny’s emissaries contacted Afeva’s lawyers to propose a compensation settlement: 30,000 euro to the families of the victims who had, in exchange, waived their right to sue as plaintiffs; at the same time, 20,000 euro were added to that figure, deposited in a specific account for medical-scientific research. “But did the Afeva association also receive a sum for each individual offer?” asked lawyer Di Amato, Schmidheiny’s defence counsel. Pesce replied: ‘Yes, we were recognised something for the procedures between citizens and Schmidheiny’s company to follow the steps of these transactions. Transactions that I think were too small to be called compensation… 30,000 euro for a person’s life…. And the money allocated to Afeva for these transactions has always been spent on activities in support of the fight against asbestos. He recalls the days of that proposal: “We did not sleep for a few nights – recalled the witness – for us it was important to do the trial that was about to begin after the hundreds of complaints that we had submitted to the Prosecutor’s Office of Turin in 2004 and bring many plaintiffs: this was, and is, our goal of justice. But we had been told clearly by Schmidheiny’s emissaries who contacted our lawyers that if we had not done this mediation as an association, the company would have done it anyway with its own representative. Well, we preferred to explain to our people what the situation was. There were widows who, out of necessity, accepted, crying…”.

The next hearing on Monday September the 20th

Next Monday’s hearing in Novara: Piercarla Coggiola, manager of the Environment and Ecology Office of the Municipality of Casale, the current Mayor Federico Riboldi and Giovanna Patrucco, daughter of the Ronzone baker who died of mesothelioma

[1] [ Valenza Po is the goldsmiths’ area a few miles from Casale, where Bruno Pesce worked before becoming a TU official and the local secretary],

[2] (the Government’s Workers Compensation Agency)

Grazie Silvana . Sarà ancora lungo questo “calvario” auguriamoci di no! Per ora ricordiamo chi non è più con noi e chi ancora oggi soffre.