SILVANA MOSSANO

Reportage udienza 10 febbraio 2023

«Voglia la Corte d’Assise dichiarare l’imputato Stephan Schmidheiny responsabile del reato di omicidio plurimo e pluriaggravato». Le parole del pubblico ministero Gianfranco Colace calano, nell’aula magna dell’Università di Novara dove si svolge il processo Eternit Bis, quando mancano pochi minuti alle 15 e 10 di venerdì 10 febbraio.

Giudici, avvocati, famigliari delle vittime, attivisti e giornalisti mettono istintivamente la sordina al respiro.

Per una buona parte della giornata, è stata presente anche una cinquantina di studenti e insegnanti casalesi degli istituti superiori Balbo, Sobrero e Leardi. Fuori, hanno esposto cartelli, articoli di giornale, ritagli delle loro ricerche, alcune scritte a caratteri cubitali: «Dubbi dubbi dubbi. Giustizia negata?».

Si è giunti alle ultimissime battute della requisitoria che ha impegnato i pubblici ministeri Gianfranco Colace e Mariagiovanna Compare per due udienze: quella del 30 gennaio e quella in corso.

La cancelliera si concentra sulla tastiera del computer per verbalizzare le conclusioni del pubblico ministero. E’ sempre un momento di apprensione quello in cui, in un processo, vengono esplicitate le richieste finali.

Questo, poi, è un processo particolare. E’ «il» processo dei 392 casalesi morti a causa del mesotelioma provocato dall’amianto. Di più: è il processo da cui si attende risposta non soltanto per le 392 vittime, ma per tutti – e sono ben di più di quelli elencati -, proprio tutti coloro che sono morti, e per i malati, e per quelli che si ammaleranno ancora. E’ il processo di una collettività che, ignara, ha subito un torto gravissimo e che da anni attende di capire chi quel torto l’ha commesso.

E’ stato l’imprenditore Stephan Schmidheiny a commetterlo quel torto? A dare una risposta a questa domanda sospesa da tempo sarà la Corte d’Assise, presieduta da Gianfranco Pezzone (affiancato dal giudice togato Manuela Massino e dai sei giudici popolari), quando pronuncerà la sentenza.

Adesso è il momento della richiesta avanzata e motivata dai pubblici ministeri, che hanno svolto le indagini, hanno raccolto e portato documenti, testimonianze, studi scientifici, hanno esposto «gli indizi più significativi» e ritengono che «tutti gli elementi costitutivi del reato di omicidio volontario, con dolo eventuale, siano risultati provati».

Colace poi scandisce le parole finali: il quadro complessivo «ci impone di chiedere la pena all’ergastolo, con isolamento diurno».

* * *

Quali sono le prove portate dai pm?

Torniamo indietro e ripercorriamo i passaggi salienti.

Nella prima parte della requisitoria, discussa lunedì 30 gennaio, erano stati affrontati i primi due aspetti: la condotta (cioè in che maniera era stato lavorato, usato e trattato l’amianto a Casale) e l’evento (cioè la morte delle 392 persone i cui nomi, cognomi e vite sono elencati nel capo di imputazione).

LE ULTIME DUE QUESTIONI

Venerdì 10 febbraio, poi, il pm Mariagiovanna Compare ha affrontato il tema del nesso causale (come ha inciso su quelle morti l’esposizione all’amianto nel decennio 1976 – 1986, quando l’imputato gestiva l’Eternit italiana) e il pm Gianfranco Colace ha affrontato la difficile questione del dolo eventuale: si verifica quando un imputato si rappresenta la concreta possibilità che un evento avvenga (in questo caso le morti per mesotelioma) e, nonostante la piena consapevolezza, agisce comunque nel modo che produrrà quell’evento.

Questa la definizione teorica che va dimostrata attraverso prove concrete.

DOLO EVENTUALE, NON INTENZIONALE

Il pm ha sgombrato il campo dall’ipotesi del «dolo intenzionale»: «Escludo che l’imputato volesse uccidere tutta una serie di persone: non sapeva i nomi e il numero delle persone che sarebbero morte, questo no». E tuttavia «si è raffigurato il rischio e ha accettato che avvenisse ciò che è avvenuto. Ha deciso consapevolmente e ha agito; e lo ha fatto per fine di lucro e con mezzo insidioso, da cui ha cercato di difendersi anche dopo la cessazione dell’attività».

PADRONI DELL’ETERNIT

Gli Schmidheiny «erano i padroni dell’Eternit, una stirpe reale e potente, già a partire dal nonno, e poi col padre di Stephan». E «l’Eternit apparteneva al cartello mondiale dei produttori e degli estrattori dell’amianto»: Colace lo dimostra pescando nella copiosa mole di documenti e soffermandosi a commentarne una parte significativa. «All’inizio degli anni Settanta – spiega – la famiglia Schmidheiny si spartisce letteralmente il mondo dell’amianto con i belgi della famiglia Emsens (con cui era strettamente imparentato il barone Louis de Cartier, ora deceduto, coimputato di Stephan Schmidheiny nel maxiprocesso per disastro doloso di Torino, ndr)».

Ne sono prove tangibili i verbali, la corrispondenza, le note e gli appunti riguardanti la Saiac (il «cartello» costituito nel 1929, del quale faceva parte prima il nonno, poi il padre dell’imputato), e successivamente i Tour d’Horizon, «in cui si discutevano e venivano prese decisioni sull’approvvigionamento dell’amianto, sul controllo della concorrenza, sulla politica dei prezzi e, da un certo momento in poi, anche sulla questione sanitaria legata alla diffusione della fibra; sono riunioni segrete, perché i cartelli erano vietati!» dice il pm.

Ma le tracce sono rimaste e sono state trovate. Ad esempio, l’annotazione di «un incontro del 13 agosto 1971 nella villa di Max Schmidheiny, padre di Stephan, a Herrburg, in Svizzera, dove i grandi imprenditori del settore lì convenuti «si rendono conto che l’industria dell’amianto sta attraversando una fase critica perché cominciano a diventare di dominio pubblico i problemi della cancerogenicità». Ricordiamo il grido di allarme dello scienziato Irving Selikoff nel 1964, al Simposio internazionale dell’Accademia delle Scienze di New York. E i giornali ne parlano (il pm richiama un articolo uscito sul New York Times il 21 gennaio 1973 che preoccupava i vertici dell’industria amiantifera; ne avevano ricevuto copia a febbraio 1973).

«Mantenendo lo standard di cinque fibre per altri quattro anni (…) secondo le predizioni di Selikoff il Dipartimento del lavoro ha condannato 20000 lavoratori a inutili decessi per cancro al polmone, 7000 a inutili decessi per mesotelioma, 7000 a inutili decessi per asbestosi nonché decessi per altri tumori. E questo senza contare gli effetti combinatori – amianto più fumo di tabacco (…). Tutto sommato Selikoff prevede che con un tratto di penna altre cinquantamila vite furono mandate in rovina».

Colace stigmatizza: «Mannaggia! Erano preoccupati… Nel ’73 sanno, dunque, che l’amianto è cancerogeno, ne parlano con apprensione, sono consapevoli che nello stabilimento di Casale “c’è un grado di inquinamento elevato nella maggior parte dei reparti”: lo scrivono loro, in una comunicazione interna del febbraio 1973. E parlano pure di inquinamento esterno, perché ci sono i risultati di alcuni studi che registrano dispersioni anche fuori dagli stabilimenti. Sanno che in Gran Bretagna la legislazione è più severa che altrove, e anche in Svezia sono più rigorosi, Schmidheiny si domanda se non sia il caso di portare quel governo in tribunale per allentare i divieti. Per l’Italia, invece, sono meno allarmati al momento, perché la “situazione è più tranquilla” scrivono».

E di fronte a questo quadro, di fronte cioè alla consapevolezza che l’amianto provoca il cancro, che cosa si pensa di fare? «Minimizzare le informazioni sulla tossicità – è la risposta che dà Colace –. Non si domandano: “Ma veramente la gente sta morendo? Se è così, forse non vale la pena smettere di usare l’amianto?”. Mai, mai, mai una preoccupazione di questo tipo».

Oltre a Saiac, ai Tour d’Horizon, alla riunione nella villa svizzera di Herrburg, c’è il convegno di Neuss nel 1976, convocato e presieduto da Stephan Schmidheiny (che dal 1975 sedeva nel consiglio si amministrazione di Eternit, assumendone il comando l’anno successivo). A Neuss si sa tutto; c’è un report che riassume quanto comunicato in quegli incontri ai massimi dirigenti Eternit: «Negli anni Sessanta sono state eseguite le prime ricerche negli Stati Uniti e in Canada ed è stata constatata l’esistenza di un effetto cancerogeno delle fibre di amianto», ma, raccomanda l’imprenditore svizzero capo di Eternit, «è decisamente importante che non si cada in forme di panico». E’ conscio di aver detto cose pesanti: «Questi tre giorni sono stati determinanti per i direttori tecnici i quali sono rimasti scioccati. Non deve succedere la stessa cosa ai lavoratori».

ARSENALE DI LETTERATURA

E allora si predispone un «arsenale di letteratura», affidandone la regia allo scienziato Robock, «non indipendente, ma pagato da Schmidheiny», che, ad esempio, «suggerisce di richiamarsi alla legislazione tedesca meno restrittiva sui limiti di diffusione delle fibre rispetto all’Osha (l’Agenzia americana che si occupa di sicurezza sul lavoro)». Nell’arsenale della letteratura rientra, tra l’altro, un opuscoletto intitolato «Amianto: la popolazione non è a rischio».

L’attività di propaganda promuove «una strategia che – spiega il pm – il cartello degli amiantiferi definisce in modo mistificatorio “utilizzo sicuro dell’amianto”. Come a mettere un freno: “calma, calma, prima di dire che l’amianto fa male!”. L’«utilizzo sicuro dell’amianto» diventa uno slogan che lo stesso Schmidheiny a Neuss ribadisce: “L’amianto può essere pericoloso se si usa male, ma se viene usato nella maniera corretta…”».

«Insomma – sintetizza Colace -, si sceglie di continuare a utilizzare questo materiale mortale». Con quali precauzioni? Sempre in un verbale di Neuss è scritto: «Dobbiamo reagire in maniera decisa (agli attacchi contro l’amianto, ndr) e combattere con tutti i nostri mezzi». Con quale impiego di risorse? Colace legge ad alta voce uno stralcio; è il capo che parla e dà indicazioni precise sul da farsi: «Assicurare all’industria amianto-cemento la possibilità di esistere per mezzo di una organizzazione ottimale della tutela del lavoro e dell’ambiente (ottimale = massima protezione con il minimo dei mezzi economici)».

E, così, dell’«arsenale di letteratura» entra a far parte anche «Auls 76» (il numero che accompagna la sigla è riferito all’anno 1976, in cui fu redatto e diffuso), che il pm definisce «il manuale della disinformazione». Contiene direttive precise sul modo con cui bisogna rispondere a chi – lavoratori, famigliari di operai, abitanti vicini allo stabilimento, sindacalisti, giornalisti, politici locali – fa domande sulla questione sanitaria, cioè sul rischio di ammalarsi per l’amianto. Quali sono le indicazioni contenute in Auls 76? Colace ne cita letteralmente alcuni passaggi: «L’amianto come tale non è pericoloso; soltanto se viene respirata polvere a granulometria sottile e visibile al microscopio (…) si può pervenire a malattie polmonari (…)». E ancora: «Non c’è alcun pericolo per le famiglie». E per chi vive nei dintorni della fabbrica il pericolo c’è? «No – è la risposta da dare, attinta ad Auls 76 -: se c’è un’emissione bassa e limitata allo scarico dei filtri può essere esclusa in maniera assoluta l’esistenza di un pericolo per coloro che abitano nei pressi dello stabilimento».

VIETATO DIRE AMIANTO

E oltre a Saiac, e oltre ai Tour d’Horizon, e oltre a Neuss, c’è Aia (Amiantus International Association), altro consesso di imprenditori dell’amianto. Nel ’77, visto che la questione sicurezza è sempre più pressante, si discute circa la richiesta di indicare sull’etichetta che l’amianto è pericoloso per la salute. Nel Regno Unito le autorità fanno pressioni. Ma i produttori sono molto perplessi, perché temono «di dover includere nella dicitura la parola “cancro”». Ne parlano a lungo: scrivere «cancro» spaventerebbe i lavoratori; perciò, si conviene di indicare «soltanto che un uso improprio del prodotto potrebbe essere dannoso alla salute». E’ in questa direzione che si decide di muoversi, per contenere allarmismi insidiosi per l’industria.

Ma qualche tempo dopo, in Inghilterra, dove le norme sono più stringenti, la società Turner & Newall sui sacchi che escono dai propri stabilimenti fa stampare la dicitura «respirare polvere di amianto può provocare cancro e altre malattie letali». La reazione? Nel 1980, la bacchettata arriva da un importante esponente del cartello mondiale, Etienne van der Rest, uno degli amministratori della Eternit belga. In una lettera indirizzata al capo della Turner & Newall, esprime grave disappunto: «Potrai comprendere – scrive – come io sia rimasto deluso» della dicitura fatta stampigliare sui sacchi inglesi. Qual è la preoccupazione di von der Rest e del “cartello”? Che «la Cee potrebbe decidere di adottare (ovunque) quell’etichetta e magari premere per un’etichetta con il teschio crociato o con qualche altro simbolo legato al rischio di cancro». Insomma, di questo rischio non si deve parlare. «Dice di essere deluso – chiosa il pm Colace –. Deluso? Ma dai! Ma si fa ‘sta cosa?».

La macchina della propaganda aveva incluso anche un più raffinato «aggiornamento» della terminologia. Dalla Svizzera, nel 1977, arriva all’amministratore delegato di Eternit Italia, Luigi Giannitrapani (con cui Stephan Schmidheiny intrattiene una corrispondenza riservatissima – “Confidential” -, con fermoposta in una casella postale di Genova), «l’invito affinché in comunicazioni, articoli, depliants, conferenze, la dicitura “prodotti di amianto-cemento” venga sostituita con “prodotti di fibro-cemento”». Sono disposizioni del capo, tratte da uno stralcio di quella corrispondenza riservata mostrato dal pubblico ministero.

Praticamente, si fa sparire l’amianto cancellandone semplicemente il vocabolo. D’altronde, sottolinea Colace, «Giannitrapani è un amministratore delegato dimezzato, espropriato dei poteri decisionali. Ai lavoratori dà solo l’informazione che il fumo fa male, ma tacendone la reale pericolosità in sinergia con l’amianto».

E, tuttavia, pur essendo state messe in atto molte strategie difensive per mimetizzare e minimizzare i rischi, la pericolosità dell’amianto esplode, non è più contenibile. «Schmidhieny non è stato in grado di gestire un destino inesorabile: l’amianto è crollato sulla questione sanitaria» afferma Colace. Ma, aggiunge, poiché «era nella stanza dei bottoni internazionale anche prima del 1976 (così come la sua presenza era incisiva e capillare nelle singole società), non poteva alzarsi e dire che bisognava smettere!».

MATERIALI ALTERNATIVI?

C’era stato un tentativo di sostituire l’amianto con materiali alternativi. Il compito di testare il terreno era stato affidato a un altro amministratore delegato, l’ultimo in Italia, Leo Mittelholzer; egli stesso ne parlò al maxiprocesso per disastro doloso, poco più di una decina di anni fa a Torino. Che cosa aveva fatto Mittelholzer? Aveva contattato i piccoli produttori italiani concorrenti, una decina, invitandoli ad abbandonare la fibra e a dirottare la produzione su fibre alternative, come Eternit aveva già fatto nei propri stabilimenti di altri Paesi. Eternit avrebbe anche messo a disposizione la propria tecnologia. Ma i «piccoli» risposero che a loro non conveniva, tanto valeva sfruttare la situazione fino a quando l’amianto non fosse stato vietato (avvenne nel 1992). E l’Eternit? Per non perdere la propria cospicua fetta di mercato, in Italia continuò a produrre come prima.

Facendo investimenti in sicurezza, per limitare il pericolo di cui era consapevole?

Secondo il pubblico ministero (e in base alla documentazione ricostruita dai consulenti della procura, e contestata da quelli della difesa) molto poco investì in sicurezza. La difesa dice: 75 miliardi di lire; e da un altro documento aziendale, emerge una cifra di poco oltre 33 miliardi. Colace, pur incerto sugli importi, replica che si trattò di afflussi di denaro per coprire perdite, mentre specificatamente per la sicurezza mostra un foglio riassuntivo con voci di spesa singole e un totale poco sotto i 4 miliardi di lire (3.943.700.000) per tutti gli stabilimenti italiani in dieci anni.

L’ABBANDONO

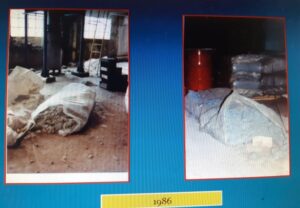

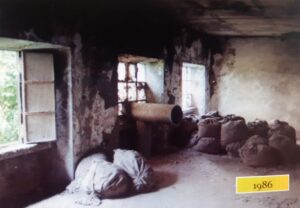

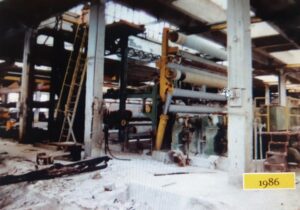

Nel 1986 l’Eternit fallisce e la fabbrica viene abbandonata. Sul maxischermo in aula scorrono le immagini interne dello stabilimento alla cessazione di botto dell’attività. «Una situazione catastrofale fu descritta dagli stessi dirigenti Eternit nei primi anni Settanta e poco meno che catastrofale è quella che rimane nella seconda metà degli anni Ottanta. E’ lì da vedere, guardate, guardate queste immagini» sollecita il pubblico ministero.

Alcune fotografie scattate nello stabilimento Eternit di Casale, abbandonato, dopo la chiusura nel 1986

Alcune fotografie scattate nello stabilimento Eternit di Casale, abbandonato, dopo la chiusura nel 1986

DOPO LA CHIUSURA

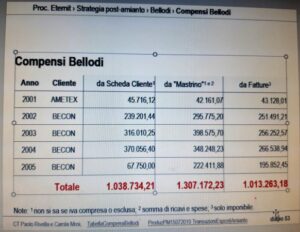

«Che cosa ha fatto l’imputato dopo il 1986? Ha continuato per vent’anni a spendere milioni per tenersi nascosto» dichiara il pm. Fa riferimento al professionista milanese, manager delle pubbliche relazioni, Guido Bellodi, «pagato profumatamente per mimetizzare Schmidheiny dietro anonime società».

Fu redatto il cosiddetto «Manuale Bellodi» con il vademecum per la protezione del capo. Che «non si doveva neppure nominare; veniva usata una sigla, STS, per indicare l’innominabile».

E ancora: «Bellodi attiva una rete di monitoraggio, anche pagando delle spie». Colace ricorda, in particolare, il nome della casalese (era emerso al maxiprocesso di Torino) che si era «infiltrata nell’Afeva (Associazione famigliari vittime amianto) e nei sindacati per acquisire informazioni e fare puntuali report periodici a Bellodi». Il pubblico ministero ne legge uno a caso, del 6 ottobre 1993: «Si sta accendendo la “miccia” sui dati relativi all’indagine epidemiologica e dei campionamenti atmosferici. Le organizzazioni sindacali sono preoccupate e stanno cercando di sensibilizzare l’opinione pubblica alla gravità del problema». L’attività di infiltrazione continua per anni. Un altro documento, che ha per «Oggetto: MONITOR», inviato a Bellodi dalla stessa fonte casalese, è datato 2 febbraio 2000: «Come di consueto, trasmetto in allegato copia degli articoli pubblicati nello scorso mese di dicembre dai giornali locali e non…». E un altro: «Il deputato casalese Angelo Muzio (Comunisti italiani) ha comunicato ufficialmente l’erogazione di finanziamenti a favore della ricerca sul mesotelioma disposti dal ministero della Sanità».

DOPO IL FALLIMENTO

Alle società svizzere facenti capo a Schmidheiny era stata suggerita l’ipotesi di riconvertire lo stabilimento casalese abbandonato, affinché non diventasse «un ingombrante “monumento all’amianto”», ma la proposta fu accantonata per motivi economici. In quella fabbrica, mollata lì imbottita di amianto, l’imprenditore svizzero non mise più mano. Quando a più sindaci casalesi che avevano testimoniato al maxiprocesso di Torino fu ripetutamente domandato: «Schmidheiny o un suo rappresentante si è mai fatto vivo offrendosi di contribuire alla bonifica?», la risposta unanime fu: «Mai».

«Dalla Svizzera arrivarono alla curatela fallimentare nove miliardi e mezzo di lire in cambio della rinuncia a ogni azione legale» spiega Colace.

Il fallimento, all’epoca, incamerò quei nove miliardi e rotti e «gli svizzeri – commenta il pm – pensarono, allora, che fosse l’ultimo esborso possibile per l’Eternit».

E invece no.

I PROCESSI

Ci fu un processo a Casale, nei confronti di alcuni dirigenti (e non del proprietario), e, poi, il maxiprocesso Eternit 1 a Torino per disastro ambientale doloso (in questo caso, per la prima volta, nei confronti della proprietà di Eternit, con condanne nei primi due gradi di giudizio e prescrizione in Cassazione) e, ancora, il processo Eternit Bis, frazionato in più filoni di cui, in Assise a Novara, si celebra quello più pesante per 392 casalesi e monferrini morti per amianto.

OGNI ESPOSIZIONE AUMENTA IL RISCHIO

«Quei 392 morti, che sono troppi, sono comunque solo una parte delle vittime causate dall’amianto a Casale» rimarca la pm Mariagiovanna Compare.

Richiama numerosi studi scientifici secondo cui «il rischio di mesotelioma c’è già a esposizioni molto basse alla fibra di amianto, ma è tanto maggiore quanto più elevata è stata la esposizione cumulativa: le molteplici circostanze di esposizione non sono in competizione tra loro, ma anzi hanno dato tutte un contributo sinergico alla manifestazione del mesotelioma».

Insiste anche sul fatto che «al crescere dell’esposizione aumenta l’anticipazione del tempo medio dell’insorgere della malattia». Quindi si muore prima.

Mostra i dati: «Nel territorio di Casale Monferrato ci sono numeri dieci volte superiori al resto del Piemonte che, pure, è una regione tra quelle più interessate dal mesotelioma».

Gira l’ultimo foglio su cui ha appuntato i vari passaggi della requisitoria e pronuncia l’ultima frase: «Riteniamo, con elevato grado di credibilità razionale, che i 392 casi sono attribuibili all’imputato Stephan Schmidheiny». Non c’è altro da dire. Ma lo ripete: «Sì, sono attribuibili a lui».

LA RICHIESTA DI CONDANNA

Ricostruito l’intero quadro probatorio, la condanna richiesta è l’«ergastolo con isolamento diurno».

ISOLAMENTO DIURNO: E’ una sorta di «ergastolo aggravato»: una pena accessoria inflitta a chi ha commesso un reato per il quale la pena dell’ergastolo non è ritenuta congrua.

Il pubblico ministero Colace non ha ancora finito.

Dopo aver tratteggiato minuziosamente la personalità dell’imprenditore Schmidheiny, spende qualche parola anche sull’imputato Schmidheiny che, a suo parere, «non merita il premio di circostanze attenuanti».

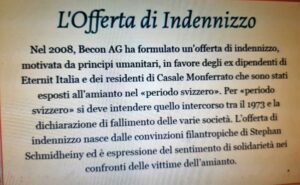

Il pm non ritiene che l’imputato possa vedersi riconosciuta come un merito «l’offerta di indennizzi che aveva avanzato alle famiglie delle vittime, motivata da principi umanitari e da convinzioni filantropiche»; quando era stata fatta? «Nel 2008, quando cioè gli era stato notificato l’avviso di chiusura delle indagini del maxiprocesso per disastro in cui era imputato. Mai prima si era manifestato il sentimento di solidarietà».

Il pubblico ministero non ritiene altresì l’imputato meritevole di attenuanti, «né generiche né di altro tipo», anche in considerazione del «comportamento processuale; semplicemente: non pervenuto».

Stephan Schmidheiny ha scelto di essere assente, rappresentato dai suoi avvocati Astolfo Di Amato e Guido Carlo Alleva. E’ un diritto lecito, sicuramente; anche se vien da dire che, forse, a ricavare il maggior guadagno nel presentarsi in aula sarebbe stato Schmidheiny stesso: per sé, per il suo riscatto umano ed etico cui pare ambire, visti gli sforzi di mostrarsi al mondo come filantropo. Certo, presentarsi è un passo che richiede coraggio, ma sarebbe (può ancora farlo, prima della fine del processo) anche una dimostrazione di dignità.

Secondo il pubblico ministero, invece, l’imputato «ha dimostrato indifferenza nei confronti di questo processo, non ha inteso far sentire la propria opinione». Non in aula, almeno. Fuori sì. Lo ricorda Colace: «A gennaio di un paio di anni fa, rilasciò un’intervista in cui lanciava strali contro il sistema giudiziario italiano».

E, poi, c’è il sito internet – www.stephanschmidheiny.com -, in cui viene raccontata la sua vita e la sua esperienza imprenditoriale in maniera un po’ diversa da come i documenti mostrano.

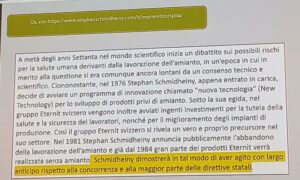

C’è scritto, nel sito, che «a metà degli anni Settanta» sulla questione dei rischi di amianto per la salute umana «si era comunque ancora lontani da un consenso tecnico e scientifico».

«No, no, non sta dicendo il vero!» chiosa Colace.

Il sito prosegue: «Ciononostante, nel 1976 Stephan Schmidheiny, appena entrato in carica, decide di avviare un programma di innovazione chiamato “nuova tecnologia” (New Technology) per lo sviluppo di prodotti privi di amianto. Sotto la sua egida, nel gruppo Eternit svizzero vengono inoltre avviati ingenti investimenti per la tutela della salute e la sicurezza dei lavoratori, nonché per il miglioramento degli impianti di produzione».

«No, non è andata così in Italia, e l’abbiamo ben visto e dimostrato, con tutte quelle prescrizioni di messa in sicurezza imposte e disattese» incalza il pubblico ministero.

Sempre nel sito si legge: «Nel 1981 Stephan Schmidheiny annuncia pubblicamente l’abbandono della lavorazione dell’amianto e già dal 1984 gran parte dei prodotti Eternit verrà realizzata senza amianto».

«Ma quando, ma come! – reagisce Colace -. E allora a Casale che cosa si è fatto fino al 1986? Io questa la prendo come una confessione dell’imputato!».

La requisitoria è finita.

LA DISCUSSIONE PROSEGUE

I legali delle parti civili parleranno nell’udienza di lunedì 27 febbraio (annullata quella di lunedì 20).

Le arringhe dei difensori sono fissate per venerdì 10 e mercoledì 29 marzo.

* * *

Translation by Vicky Franzinetti

Eternit Hearing February the 10th , 2023

by Silvana MOSSANO

“May the Assize Court declare the defendant Stephan Schmidheiny responsible for the crime of multiple and aggravated murders”. The words of public prosecutor Gianfranco Colace, in the courtroom of the University of Novara where the Eternit Bis trial is being held, when it is close to 3.10pm on Friday February the 10th.

Judges, lawyers, victims’ families, activists and journalists instinctively hold their breath. For most of the day, about fifty students and teachers from the Casale High Schools Balbo, Sobrero and Leardi were also present. Outside, they displayed placards, newspaper articles, clippings of their research, some written in large letters: ‘Doubts doubts. Justice denied?”.

We have reached the very last moments of the indictment that has seen prosecutors Gianfranco Colace and Mariagiovanna Compare speak in the last two hearings: the one on 30 January and the one in progress.

The court reporter concentrates on the computer keyboard to record the prosecutor’s conclusions. It is always a tense moment when the final demands are made.

This, then, is a special trial. It is ‘the’ trial of the 392 Casale residents who died of mesothelioma caused by asbestos. What’s more: it is the trial from which answers are expected not only for the 392 victims, but for everyone – and they are far more than those listed -, precisely all those who have died, and for those who are ill, and for those who will become ill in the future. It is the trial of a community that, unaware, suffered a very serious wrong and has been waiting for years to understand who committed that the crime.

Was it Stephan Schmidheiny who committed that crime? The answer to this question will be given by the Assize Court, presided over by Gianfranco Pezzone (with judge Manuela Massino and six jury), when it pronounces the verdict.

Now the time has come for the PP to make their requests and motivated them: they have carried out the investigations, gathered and brought documents, testimonies, scientific studies, set out ‘the most significant clues’ and believe that ‘all the constituent elements of the crime of murder, with possible intent, have been proven’. PP Colace spell out the final words: the overall picture ‘requires us to ask for life imprisonment, with day solitary confinement’.

* * *

What is the evidence brought by the prosecutors?

Let us go back and review the main points .

In the first part of the indictment, discussed on Monday 30 January, the first two features were addressed: conduct (i.e. how asbestos was worked, used and treated at Casale) and the event (i.e. the death of the 392 people whose names, surnames and lives are listed in the indictment).

THE LAST TWO ISSUES

Then, on Friday 10 February, public prosecutor Mariagiovanna Compare addressed the issue of the causal link (how did exposure to asbestos in the decade 1976-1986, when the defendant managed the Italian Eternit company, affect those deaths) and public prosecutor Gianfranco Colace addressed the difficult issue of possible intent: it occurs when a defendant represents the concrete possibility that an event will occur (in this case, deaths from mesothelioma) and, despite full awareness, acts in a way that will produce that event.

This is the theoretical definition that must be proved by evidence.

POSSIBLE INTENT, NOT INTENTIONAL

The public prosecutor cleared the field of the hypothesis of ‘intentional malice’: ‘I rule out that the defendant wanted to kill a whole series of people: he did not know the names and number of people who would die, this did not’. And yet ‘he portrayed the risk to himself and accepted that what happened would happen. He made a conscious decision and acted; and he did so for profit and by an insidious means, from which he tried to defend himself even after the cessation of business’.

The ETERNIT OWNERS

The Schmidheinys ‘owned Eternit, a ‘royal’ and powerful lineage, starting with their grandfather and then with Stephan’s father’. And ‘Eternit belonged to the worldwide cartel of asbestos producers and extractors’: Colace proved this with the copious amount of documents and pausing to comment on a significant part of them. “In the early 1970s,” he explains, “the Schmidheiny family literally shared the world of asbestos with the Belgian Emsens family (with whom Baron Louis de Cartier, now deceased, co-defendant of Stephan Schmidheiny in the maxi-trial for intentional disaster in Turin).

Tangible evidence of this are the minutes, correspondence, notes and memos concerning Saiac (the ‘cartel’ set up in 1929, of which first the grandfather, then the father of the defendant was a member), and later the Tour d’Horizon, ‘in which decisions were discussed and taken on asbestos procurement, competition control, price policy and, from a certain moment onwards, also on the health issue linked to the spread of the fibre; these are secret meetings, because cartels were forbidden!

Traces remained and were found. For example, the annotation of ‘a meeting on 13 August 1971 in the villa of Max Schmidheiny, Stephan’s father, in Herrburg, Switzerland, where the big entrepreneurs of the sector who were gathered there “realised that the asbestos industry was going through a critical phase because the problems of carcinogenicity were beginning to become public knowledge’. We remember the cry of alarm by the scientist Irving Selikoff in 1964, at the International Symposium of the New York Academy of Sciences. And the newspapers talk about it (the pm recalls an article in the New York Times on 21 January 1973 that worried the top management of the asbestos industry; they had received a copy in February 1973).

“By maintaining the five-fiber standard for another four years (…) according to Selikoff’s predictions, the Labor Department has condemned 20,000 workers to unnecessary deaths from lung cancer, 7,000 to unnecessary deaths from mesothelioma, 7,000 to unnecessary deaths from asbestosis as well as deaths from other cancers. And this is without counting the combinatorial effects – asbestos plus tobacco smoke (…). All in all, Selikoff predicted that with a stroke of the pen another fifty thousand lives were sent to ruin’.

Colace stigmatises: ‘Damn! They were worried… In 1973 they knew, therefore, that asbestos was carcinogenic, they spoke of it with apprehension, they were aware that in the Casale plant ‘there was a high level of pollution in most of the departments’: they wrote this themselves, in an internal communication of February 1973. And they also speak of external pollution, because there are the results of some studies that record dispersions even outside the plants. They know that in Great Britain the legislation is stricter than elsewhere, and even in Sweden they are stricter, Schmidheiny wonders whether it is not a case of taking that government to court to loosen the bans. For Italy, on the other hand, they are less alarmed at the moment because the ‘situation is calmer’, they write’.

And faced with this picture, that is, faced with the knowledge that asbestos causes cancer, what are they planning to do? ‘Minimise information on toxicity,’ is Colace’s answer. They never asked themselves: ‘Are people really dying? If so, perhaps it is not worth stopping using asbestos?’ Never, never such a concern’.

In addition to Saiac, the Tour d’Horizon, and the meeting in the Swiss villa in Herrburg, there is the Neuss conference in 1976, convened and chaired by Stephan Schmidheiny (who sat on Eternit’s board of directors from 1975, taking over in the following year). Everything is known in Neuss; there is a report summarising what was communicated in those meetings to the top Eternit executives: ‘In the 1960s, the first research was carried out in the United States and Canada and the existence of a carcinogenic effect of asbestos fibres was ascertained’, but, the Swiss entrepreneur head of Eternit recommends, ‘it is definitely important that we do not fall into forms of panic’. He is aware that he has said some heavy things: ‘These three days were decisive for the technical directors who were shocked. The same thing must not happen to the workers’.

LITERATURE

And so an ‘arsenal of literature’ was prepared, entrusting its direction to the scientist Robock, ‘not independent, but paid by Schmidheiny’, who, for example, ‘suggests referring to German legislation that is less restrictive on fibre limits than Osha (the American agency that deals with safety at work)’. The arsenal of literature includes a pamphlet entitled ‘Asbestos: the population is not at risk’.

The propaganda promotes ‘a strategy that,’ explains the prosecutor, ‘the asbestos cartel mystifyingly defines as ‘safe use of asbestos’. As if to put a brake on it: “calm down, calm down, before saying that asbestos is bad for you!”. The ‘safe use of asbestos’ becomes a slogan that Schmidheiny himself in Neuss reiterates: ‘Asbestos can be dangerous if it is used wrongly, but if it is used in the right way…'”.

‘In short,’ summarised Colace, ‘one chooses to continue using this deadly material’. With what precautions? Again in a Neuss report it is written: ‘We must react decisively (to the attacks against asbestos, ed.) and fight with all our means’. With what deployment of resources? Colace read an excerpt out loud; it is the boss who speaks and gives precise indications as to what is to be done: ‘Ensure that the asbestos-cement industry can exist by means of an optimal organisation of labour and environmental protection (optimal = maximum protection with minimum economic means)’.

And, thus, the ‘arsenal of literature’ also includes ‘Auls 76’ (the number accompanying the acronym refers to the year 1976, in which it was drafted and circulated), which the public prosecutor defines as ‘the manual of disinformation’. It contains precise directives on how to respond to those – workers, workers’ relatives, residents near the plant, trade unionists, journalists, local politicians – who ask questions on the health issue, i.e. the risk of falling ill from asbestos. What are the indications contained in Auls 76? Colace literally quotes a few passages: ‘Asbestos as such is not dangerous; only if fine-grained dust visible under a microscope is breathed in (…) can lung diseases occur (…)’. And again: ‘There is no danger for families. And for those living around the factory is there any danger? “No,’ is the answer to be given, drawn from Auls 76, ‘if there is a low emission and limited to the discharge of filters, the existence of a danger for those living near the factory can be absolutely excluded.

FORBIDDEN TO SAY ASBESTOS

And in addition to Saiac, and in addition to Tour d’Horizon, and in addition to Neuss, there is Aia (Amiantus International Association), another forum of asbestos entrepreneurs. In ’77, as the safety issue was becoming increasingly urgent pressing, there was a discussion about the requirement to indicate on the label that asbestos was hazardous to health. In the UK, the authorities lobby. Manufacturers are very perplexed, because they fear ‘having to include the word “cancer” in the wording’. They spoke about it at length: writing ‘cancer’ would frighten workers; therefore, they agree to indicate ‘only that improper use of the product could be harmful to health’. It is in this direction that it is decided to move, to contain alarmism that is insidious to the industry.

Some time later, in England, where regulations are more stringent, the company Turner & Newall had the words ‘breathing asbestos dust can cause cancer and other lethal diseases’ printed on the bags leaving its factories. The reaction? In 1980, the stick came from a leading exponent of the global cartel, Etienne van der Rest, one of the directors of Belgian Eternit. In a letter addressed to the head of Turner & Newall, he expresses his grave disappointment: ‘You will understand,’ he writes, ‘how disappointed I am’ with the wording printed on the English sacks. What is the concern of von der Rest and the ‘cartel’? That ‘the EEC (as the EU was then called) might decide to adopt (everywhere) that label and perhaps press for a label with a criss-cross skull or some other symbol related to cancer risk’. In short, this risk must not be spoken of. ‘He says he is disappointed,’ PP Colace concluded. Disappointed? No way?”.

The propaganda machine had also included a more refined ‘updating’ of terminology. From Switzerland, in 1977, the managing director of Eternit Italia, Luigi Giannitrapani (with whom Stephan Schmidheiny kept a very confidential correspondence – ‘Confidential’ -, with a poste restante in a post box in Genoa), received ‘an invitation to replace the wording “asbestos-cement products” with “fibre-cement products” in communications, articles, brochures, conferences’. These are provisions of the chief, taken from an excerpt of that confidential correspondence shown by the public prosecutor.

Basically, you make asbestos disappear by simply deleting the word. On the other hand, Colace emphasised, ‘Giannitrapani is a halved managing director, dispossessed of decision-making powers. He only gave the workers the information that smoking is bad for them, but is silent about its real danger in synergy with asbestos’.

Although many defensive strategies had been put in place to camouflage and minimise the risks, the danger of asbestos explodes, it is no longer containable. ‘Schmidhieny was unable to manage an inexorable fate: asbestos collapsed on the health issue,’ says Colace. But, he adds, since ‘he was in the international control room even before 1976 (just as his presence was incisive and widespread in individual companies), he could not stand up and say that it had to stop!’

ALTERNATIVE MATERIALS?

There had been an attempt to replace asbestos with alternative materials. The task of testing the ground had been entrusted to another managing director, the last one in Italy, Leo Mittelholzer; he himself spoke about it at the maxi-trial for malicious disaster a little over a decade ago in Turin. What had Mittelholzer done? He had contacted the small competing Italian manufacturers, about ten of them, inviting them to abandon the fibre and to divert production to alternative fibres, as Eternit had already done in its plants in other countries. Eternit would also make its technology available. But the ‘little guys’ replied that it was not convenient for them, they might as well exploit the situation until asbestos was banned (this happened in 1992). And Eternit? In order not to lose its large share of the market, it continued to produce in Italy as before.

By making investments in safety, to limit the danger of which it was aware?

According to the public prosecutor (and based on the documentation reconstructed by the prosecutor’s consultants, and contested by those of the defence) very little was invested in safety. The defence says: 75 billion lire; and another company document shows a figure of just over 33 billion. Colace, although uncertain about the amounts, replied that these were inflows of money to cover losses, while specifically for safety he shows a summary sheet with individual expenditure items and a total of just under 4 billion lire (3,943,700,000) for all the Italian plants over ten years.

BANKRUPTCY

In 1986, Eternit went bankrupt and the factory was abandoned. On the big screen in the courtroom, the internal images of the factory at the sudden cessation of activity run. “A catastrophic situation was described by the Eternit managers themselves in the early 1970s and little less than catastrophic is what remains in the second half of the 1980s. It is there to be seen, look at these pictures,’ urged the prosecutor.

AFTER THE CLOSURE

“What did the defendant do after 1986? He continued for 20 years to spend millions to hide,’ says the prosecutor. He refers to the Milanese professional, public relations manager Guido Bellodi, ‘paid handsomely to camouflage Schmidheiny behind anonymous companies’.

[The so-called ‘Bellodi Manual’ with the orders to protect the boss. Who ‘was not even to be named; an acronym was used, STS, to indicate the unmentionable’.

And again: ‘Bellodi activated a monitoring network, even paying spies’. Colace recalls, in particular, the name of the Casale woman (it had emerged at the maxi-trial of Turin) who had ‘infiltrated the Afeva (Associazione famigliari vittime amianto – Association of asbestos victims) and the trade unions to acquire information and make periodic reports to Bellodi’. The public prosecutor read one at random, dated 6 October 1993: ‘The “fuse” is being lit on the data concerning the epidemiological investigation and atmospheric sampling. The trade unions are concerned and are trying to raise public awareness of the seriousness of the problem’. The infiltration activity continues for years. Another document, with ‘Subject: MONITOR’, sent to Bellodi by the same Casale source, is dated 2 February 2000: ‘As usual, I am enclosing a copy of the articles published last December in local and other newspapers…’. And another: ‘The Casale MP Angelo Muzio (of the Italian Communist Party) officially announced the disbursement of funding for mesothelioma research arranged by the Ministry of Health’.

AFTER THE BANKRUPTCY

The Swiss companies headed by Schmidheiny had been suggest reconverting the abandoned Casale factory so that it would not become ‘a bulky “asbestos monument”‘, but the proposal was shelved for economic reasons. The Swiss entrepreneur never again laid a hand in that factory, which had been abandoned and stuffed with asbestos. When several mayors from Casale who had testified at the maxi-trial in Turin were repeatedly asked: “Has Schmidheiny or one of his representatives ever turned up offering to contribute to the reclamation?”, the unanimous answer was: “Never”.

‘Nine and a half billion lire arrived from Switzerland to the bankruptcy receivership in exchange for waiving all legal action,’ Colace explains.

The bankruptcy, at the time, cashed in those nine and a half billion lire and ‘the Swiss,’ comments the prosecutor, ‘thought at the time that it was the last possible disbursement for Eternit.

THE TRIALS

There was a trial in Casale, against some executives (and not the owner), and then the Eternit 1 maxi-trial in Turin for malicious environmental disaster (in this case, for the first time, against the owners of Eternit, with convictions in the first two levels of judgment and acquittal for the statute of limitations in Cassation) and, again, the Eternit Bis trial, divided into several strands of which, in the Assize in Novara, the heaviest one is being celebrated for 392 people from Casale and Monferrato who died from asbestos.

EACH EXPOSURE INCREASED THE RISK

“Those 392 deaths, which are too many, are in any case only a part of the victims caused by asbestos in Casale,” remarks public prosecutor Mariagiovanna Compare.

She recalls numerous scientific studies according to which ‘the risk of mesothelioma already exists at very low exposures to asbestos fibres, but is all the greater the higher the cumulative exposure: the multiple circumstances of exposure are not in competition with each other, but on the contrary have all made a synergic contribution to the manifestation of mesothelioma’.

He also insisted on the fact that ‘as exposure increases, the average time of onset of the disease increases. So you die sooner.

He showed the data: ‘In the Casale Monferrato area there are numbers ten times higher than in the rest of Piedmont, which is also one of the regions most affected by mesothelioma’.

He turns over the last sheet of paper on which he has noted the various passages of the indictment and pronounces the last sentence: ‘We believe, with a high degree of rational credibility, that the 392 cases are attributable to the defendant Stephan Schmidheiny’. There is nothing more to be said. But he repeats: ‘Yes, they are attributable to him’.

DEMANDS

Having reconstructed the entire evidentiary picture, the requested sentence is ‘life imprisonment with daytime isolation’.

DAYTIME ISOLATION: This is a kind of ‘aggravated life imprisonment’: an accessory penalty imposed on a person who has committed a crime for which life imprisonment is not considered appropriate.

Prosecutor Colace had not yet finished.

After minutely sketching the personality of the entrepreneur Schmidheiny, he also spent a few words on the defendant Schmidheiny, who, in his opinion, ‘does not deserve the award of mitigating circumstances’.

The prosecutor did not believe that the defendant can be credited with ‘the offer of compensation he had made to the victims’ families, motivated by humanitarian principles and philanthropic convictions’; when was this made? “In 2008, that is, when he had been served with the notice of closure of the investigation of the maxi disaster trial in which he was a defendant. Never before had the feeling of solidarity been expressed’.

The public prosecutor also did not consider the defendant deserving of extenuating circumstances, ‘neither generic nor of any other kind’, also in view of his ‘trial behaviour; quite simply: he has not been found guilty’.

Stephan Schmidheiny chose to be absent, represented by his lawyers Astolfo Di Amato and Guido Carlo Alleva. It is his right to do so , certainly, although it must be said that Schmidheiny himself would perhaps have gained the most from appearing in court: for himself, for his human and ethical redemption to which he seems to aspire, given his efforts to show himself to the world as a philanthropist. Of course, presenting himself is a step that requires courage, but it would also be (he can still do it, before the end of the trial) a demonstration of dignity.

According to the prosecutor, however, the defendant ‘showed indifference to this trial, he did not intend to make his opinion heard’. Not in the courtroom, at least. Outside, yes. Colace recalled: ‘In January, a couple of years ago, he gave an interview in which he hurled accusations at the Italian justice system.

And, then, there is the website – www.stephanschmidheiny.com -, where his life and business experience is recounted a little differently from what the documents show.

It says, on the site, that ‘in the mid-1970s’ on the question of the risks of asbestos for human health ‘we were still far from a technical and scientific consensus’.

“No, no, he’s not telling the truth!” chides Colace.

The site continues: “Nevertheless, in 1976 Stephan Schmidheiny, who had just taken office, decided to start an innovation programme called ‘New Technology’ (New Technology) for the development of asbestos-free products. Under his aegis, the Swiss Eternit group also initiated huge investments in the protection of workers’ health and safety, as well as in the improvement of production facilities’.

‘No, this was not the case in Italy, and we have seen and proven it, with all those safety measures imposed and disregarded,’ urges the public prosecutor.

The website also reads: ‘In 1981, Stephan Schmidheiny publicly announced the abandonment of asbestos processing and by 1984, a large part of Eternit’s products were already being manufactured without asbestos’.

“But when, but how! – reacts PP Colace – So what was done in Casale until 1986? I take this as a confession by the defendant!’.

THE HEARINGS CONTINUES

The civil parties’ lawyers will speak at the hearing on Monday, 27 February (Monday the 20th cancelled).

The defense lawyers’ speeches are scheduled for Friday the 10th of March and Wednesday 29 th of March 2023

Mille volte grazie Silvana!

Grande, ottima ricostruzione ! Una sintesi molto generosa per l’impegno dedicato e per la corretta esposizione ancorata alla realtà. Speriamo che della richiesta di condanna (assoluta novità per un crimine d’impresa) alla fine rimanga qualche cosa. Certo che x abbattere certi “muri” bisogna insistere molto!…

Grazie . Restiamo in fiduciosa attesa.

Grazie a te, i casalesi si rendono conto del disastro che abbiamo vissuto e che vivremo ancora per molti anni. La speranza di giustizia non ci deve abbandonare.

Ergastolo! Con isolamento diurno …richiede calmo Gianfranco Colace;

Alla Donna più importante della mia vita!… dice Marco Mengoni

(attualità, dedica alla Mamma per vittoria Festival S. Remo);

Divisi si perde! …biascicava ieri la Moratti.

Ebbene! Per me l’Ergastolo richiesto doveva essere più aggravato: “ostativo”.

Ostativo poiché il delitto contestato ritengo sia ancor più grave, “in associazione”.

In associazione con tutti coloro che in qualche modo hanno “favorito” o accettato l’accadere di questa situazione, nessuno escluso.

Avendo ascoltato pazientemente tutti gli interventi dei vari scienziati e periti delle due parti, posso affermare oggi con assoluta certezza che:

“la Donna più importante della mia vita”, l’ha uccisa l’Eternit !

Non so ancora se l’ha uccisa volontariamente l’unico imputato chiamato a risponderne.

Per saperlo devo ancora sentire gli avvocati di parte civile e i difensori.

Invece mi par di capire che la gran parte degli eredi dei moltissimi morti oggetto del dibattimento, abbiano già capito tutto! (uniti si vince?).

Spero almeno che presenzino in massa il 27 corrente (salvo giustificate situazioni), alla requisitoria dei rispettivi avvocati di parte civile.

Giusto per rispetto nei confronti di tutti coloro che hanno perorato,

con impegno, dedizione e convinzione, la nostra/loro causa.

Grazie Silvana.

Grazie Silvana, sempre, per quello che fai per noi.