«(…) e il tormentato esaminator di sé stesso, per rendersi ragione di un sol fatto, si trovò ingolfato nell’esame di tutta la sua vita. Indietro, indietro, d’anno in anno, d’impegno in impegno, di sangue in sangue, di sceleraggine in sceleraggine: ognuna ricompariva all’animo consapevole e nuovo, separata dai sentimenti che l’avevano fatta volere e commettere, ricompariva con una mostruosità che quei sentimenti non vi avevano allora lasciato scorgere». [Alessandro Manzoni, I Promessi Sposi, Capitolo XXI, la notte dell’Innominato]

SILVANA MOSSANO

Reportage udienza 7 giugno 2023 – Cronaca di una lunga attesa

Stephan Schmidheiny, ultimo patron dell’Eternit in vita, è stato condannato: riconosciuto colpevole di omicidi plurimi colposi, pluriaggravati «dall’aver commesso il fatto con violazione delle norme per la prevenzione degli infortuni sul lavoro» e anche «dall’aver agito nonostante la previsione dell’evento».

La Corte d’Assise di Novara, nell’aula magna dell’Università dove si è celebrato il processo Eternit Bis, gli ha inflitto 12 anni di reclusione.

Il reato contestato è stato riqualificato da omicidio volontario (con dolo eventuale) a omicidio colposo (con colpa cosciente).

Ciò ha comportato che per un certo numero di casi sia stata dichiarata la prescrizione.

Schmidheiny colpevole: inflitti 12 anni per plurimi omicidi colposi

Analizziamo bene la sentenza.

C’è un primo gruppo di vittime (in tutto 147) per le quali l’imputato è stato condannato a 12 anni; questo gruppo, a sua volta, si distingue in un sottogruppo A (9 vittime) per il quale sono state addebitate a Schmidheiny entrambe le aggravanti (violazione delle norme di prevenzione e colpa cosciente) e in un sottogruppo B (138 vittime) per il quale gli è stata addebita solo l’aggravante della violazione delle norme.

C’è un secondo gruppo di vittime (in tutto 199) per le quali è scattata la prescrizione.

Quando è scattata la prescrizione? Nei casi in cui siano trascorsi almeno 15 anni dalla data del decesso. Ciò significa che le 199 vittime di questo secondo gruppo sono morte da più di 15 anni.

Altro interrogativo: nei confronti di questi 199 casi prescritti, Schmidheiny è colpevole? Nel nostro diritto processuale, se dagli atti emerge che l’imputato era innocente, anche quando un reato risulta prescritto il giudice non si limita a dichiarare di «non doversi procedere per intervenuta prescrizione», ma deve emettere specificatamente una sentenza di assoluzione (con le formule «perché il fatto non sussiste» o «per non aver commesso il fatto»). In questo caso, invece, per i 199 non è avvenuto così; pertanto, si ritiene ci fossero elementi probatori che avrebbero portato la Corte a emettere una sentenza di condanna per le responsabilità di morte anche nei confronti di questo gruppo, ma la prescrizione ha fatto da ghigliottina.

Laddove, invece, i giudici hanno riconosciuto che non c’erano prove per condannare, hanno emesso una specifica sentenza di assoluzione: per 46 vittime l’imputato è stato assolto. Le motivazioni della sentenza, che saranno depositate entro 90 giorni, spiegheranno se la decisione sia da attribuire a diagnosi incerte o alla difficoltà di associare la malattia a un preciso periodo di vita delle vittime a Casale.

L’imputato, oltre che alla interdizione dai pubblici uffici per 5 anni, è stato altresì condannato a risarcire in separate cause civili diverse parti costituite (tra cui Presidenza del Consiglio, Regione Piemonte, Provincia di Alessandria e Comune di Casale Monferrato). Fin da ora, però, la Corte ha disposto che Schmidheiny versi provvisionali immediatamente esecutive a favore di un lungo elenco di enti, sindacati, associazioni e singole parti lese. La più consistente è stata assegnata al Comune di Casale (50 milioni di euro), 30 milioni alla Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri e mezzo milione di euro all’Afeva. In totale oltre 86 milioni di euro, cui si aggiunge l’obbligo di pagamento delle spese di costituzione delle parti civili per un ammontare superiore a 200 mila euro.

Si è concluso così, mercoledì 7 giugno, il giudizio di primo grado del processo Eternit Bis, dopo 42 udienze che si sono svolte lungo due anni, a partire dal 9 giugno 2021.

DI BUON’ORA

Alle 8 e un quarto l’aula magna è vuota, le luci sono basse, l’atmosfera soffusa. C’è soltanto il tecnico che gestisce l’impianto fonico, si aggira tra le varie postazioni, prova e controlla che tutto sia a posto. E’ una giornata storica. In due anni si è imparato a conoscersi. Ci si saluta, è un po’ un addio: «E’ l’ultima volta che ci incontriamo…».

Prendiamo posto sulla poltrona occupata fin dalla prima udienza, la borsa a fianco, con il quaderno per gli appunti, qualcosa da leggere durante le pause, le Bic, sempre una di scorta, non si sa mai.

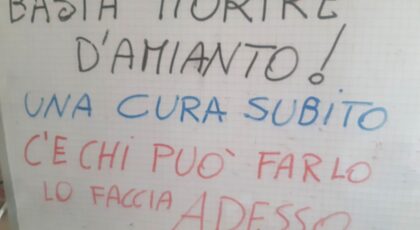

Fuori, i primi attivisti allestiscono la scena, l’hanno fatto, instancabili, all’inizio di ogni udienza. Ma per l’ultima anche di più: alle transenne e ai muri appendono le bandiere tricolore con la scritta Eternit Gistizia e quelle gialle di Legambiente, e poi di Medicina Democratica e Aiea, e delle varie sigle sindacali, i cartelloni con i lavori degli studenti, anche quelli che hanno partecipato di recente al concorso sull’ambiente «Premio Guglielmo Cavalli», era un sindacalista morto per l’amianto. In primo piano, un lungo striscione azzurro, nuovo: è la riproduzione del basamento del Monumento Vivaio Eternot, che si trova a Casale nel Parco costruito sulle ceneri dello stabilimento Eternit, nel quartiere Ronzone. E’ stampata la frase: «I fazzoletti intrisi delle nostre lacrime metteranno le ali e voleranno lontano per sviluppare profonde radici di giustizia».

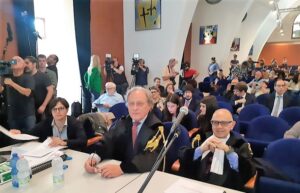

Via via, alla spicciolata, in aula arrivano i primi avvocati; i giornalisti con le troupe, italiane e straniere, fanno a gara per conquistarsi le posizioni migliori dove sistemare i cavalletti con le telecamere. Poi i pubblici ministeri, con i loro collaboratori e consulenti, altri avvocati delle difese e delle parti civili, famigliari delle vittime, sindacalisti e sanitari che hanno accompagnato coraggiosamente la malattia di tanti pazienti, attivisti, parecchi sono arrivati con un pullman speciale o in una processione di auto. Si sono mobilitati anche dagli Usa, dalla Francia, dall’Olanda, dalla Svizzera, dalla Spagna. C’è molta animazione, tra onde di toghe e brusii.

ENTRANO I GIUDICI

Poi arrivano i giudici: il presidente Gianfranco Pezone e la collega Manuela Massino indossano il bavaglino e la toga, i popolari posizionano la fascia tricolore a tracolla. Alle 9 e mezza, comincia l’appello, un nome via l’altro. «Ho chiamato tutti? Bene».

Quella di mercoledì 7 giugno è, sì, l’udienza del verdetto, ma c’è ancora spazio per le repliche; vero che tutte le parti erano state invitate a depositarle per iscritto entro metà maggio, ma i pm sono decisi a spendersi fino all’ultimo. Gianfranco Colace lo dice quasi a sé stesso: «E’ un processo troppo importante e delicato, non possiamo dare per scontato di aver esaurito ogni argomento… forse non abbiamo detto tutto, forse occorre ancora puntualizzare…». E puntualizza. Si sofferma sul polverino, «non è vero che lo abbiamo fatto sparire dal processo, è “un” colpevole, ma non è “il” colpevole», a dire che è una fonte di esposizione, ma, a parere dell’accusa, le più cospicue erano riconducibili all’intensa e incontrollata attività dello stabilimento e alla mancata applicazione delle misure che avrebbero dovuto contenerle. Certo, il polverino era pericoloso, tanto che i vertici dell’Eternit, a un certo punto, nel decennio di gestione di Stephan Schmidheiny, avevano diffidato la ditta Bagna, appaltatrice dello smaltimento dei rifiuti, di non distribuirlo più ai cittadini che ne avessero fatto richiesta. Diffida che l’appaltatore non ha confermato, ma, pur dandola per vera, «alla popolazione, invece – sottolinea Colace -, mai nessuna informazione è stata data sulla grave pericolosità di questo materiale». Chiosa l’avvocato Esther Gatti, di parte civile: «Dov’è stata apposta la scritta “L’amianto nuoce alla salute”? Noi non l’abbiamo mai vista!».

Sul fatto, richiamato dalla difesa, che la lavorazione dell’amianto sia stata un’attività lecita in Italia fino al 1992 (quindi oltre il decennio 1976-1986 di gestione Schmidheiny), «niente da obiettare – commenta il pm, – ma un’attività lecita va svolta lecitamente! Norme a cui attenersi ce n’erano, ma non sono state osservate, lo dimostrano le decine e decine di prescrizioni imposte dagli organismi di ispezione e controllo».

«L’amianto uccide – ha rimarcato Colace -: personalmente Schmidheiny aveva tutte le conoscenze. Lo sapeva, lo sapeva ed è andato avanti ugualmente, a costo di causare l’evento lesivo». Le morti.

La pm Mariagiovanna Compare insiste sulla certezza delle diagnosi, in parte contestate dai ct della difesa; «erano mesoteliomi – rimarca – ed è stato escluso con certezza che altre malattie siano state la causa di morte». Ribadisce con forza «la tesi, prevalente in ambito scientifico, della rilevanza della dose cumulativa di esposizione», come illustrata e argomentata dal consulente Corrado Magnani, «la cui autorevolezza e indipendenza di giudizio è acclarata».

Per le parti civili, l’avvocato Maurizio Riverditi è convinto: «E’ emerso in questo processo che Schmidheiny, di fronte al dubbio che delle persone potessero morire, non ha pensato di fermarsi, ma ha deciso di proseguire con l’impiego dell’amianto». Poi guardando a uno a uno i giudici: «Se una delle 392 vittime fosse un vostro famigliare, l’imputato lo chiamereste omicida». Sulle richieste risarcitorie interviene l’avvocato Esther Gatti che rappresenta il Comune di Casale. Il sindaco Federico Riboldi, presente all’udienza, si sporge per non perdere una parola. Dice il legale: «Abbiamo chiesto un risarcimento di 50 milioni e la difesa ci contesta la richiesta perché dice che è riferita a un danno prescritto e, in più, che non può essere riconducibile alle morti. Eh no; intanto, molte delle spese di bonifica sono state sostenute dopo la prescrizione pronunciata dalla Cassazione nel 2014 per il Maxiprocesso Eternit Uno riferito al disastro ambientale. Inoltre, la nostra richiesta di risarcimento è, sì, riconducibile alle morti proprio per come sono state cagionate dalle condotte dell’imputato».

LA PAROLA ALLE DIFESE

I difensori Astolfo Di Amato e Guido Carlo Alleva chiedono cinque minuti di sospensione, per un confronto. Non si aspettavano ampie repliche orali. Rientrano e si richiamano alle articolate relazioni scritte che hanno depositato a suo tempo, insistendo su un paio di punti. «Qui si dice che Schmidheiny sapeva; ma come: Schmidheiny sapeva forse più degli ispettori e degli scienziati? Nessuno di loro ha mai detto che bisognava sospendere l’attività! Soltanto al Consensus Scientifico del 1997 si è affermato definitivamente che non era possibile lavorare l’amianto in sicurezza. 1997, undici anni dopo la chiusura dello stabilimento di Casale. Prima si credeva di sì».

Alleva, pur riconoscendo «la drammaticità di questa vicenda dal punto di vista umano», insiste sul fatto che «non si può negare la storicità: bisogna collocarci là, tra il 1976 e il 1986, e tener conto delle conoscenze dell’epoca. Altrimenti, è un accanimento, un’ingiustizia».

Ritorna il silenzio. Nessuno chiede più di intervenire. Il presidente verbalizza: «Termina la fase della discussione e comincia quella della deliberazione». Ma prima che la Corte si ritiri in camera di consiglio per decidere il verdetto, Pezone si rivolge alla platea: «Esprimo, a nome mio e della Corte, un grosso ringraziamento a tutte la parti processuali per l’attenzione e la competenza con cui avete trattato temi così complessi e per la correttezza del confronto». Gratitudine anche alle istituzioni di Novara e al Rettore dell’Università.

I giudici si alzano, Pezone dice che «ci vorrà un po’ di tempo»: informerà la cancelliera almeno un’ora prima del momento in cui sarà letta la decisione finale.

Alle 11,30 la Corte si ritira. L’attesa durerà sette ore e un quarto.

PRONOSTICI E SCARAMANZIA

Usciti i giudici, la variegata folla si scioglie e si anima. Nei corridoi e all’esterno (nell’aula no, è vietato) i giornalisti vanno a caccia di interviste e gli intervistati vengono strattonati da un microfono a una telecamera senza tregua. Altri si sparpagliano, chi a mangiare in mensa («mhm, non è tanto buono…») chi in bar e locali poco distanti.

Nell’aula si rimane in pochi, pochissimi. Qualcuno sussurra: «Tu che dici? Come pensi che decideranno?». Ma nessuno cede all’azzardo di fare previsioni, nel timore di essere smentito. Aleggia qualche ipotesi vaga «se decidono così… se dovessero tener conto di…». Meglio stare abbottonati per scaramanzia.

Si affacciano incerti alcuni studenti universitari. «Noi non facciamo Giurisprudenza, siamo di Economia – chiariscono un po’ intimiditi -, ma vorremmo capire…». Incrociano Assunta Prato, vedova dell’amianto; e lei spiega con semplicità e chiarezza, come se fossero alunni suoi. I ragazzi sgranano gli occhi: «Noi siamo qui, a Novara, a poca distanza da Casale, ma non sappiamo niente di tutto questo. Sì, avevamo sentito parlare di amianto, ma che fosse così pericoloso… mortale…». Sono scossi, si è squarciato un velo. «Ma quanti anni ha l’imputato?». Assunta è pronta: «Settantasei, la stessa età che oggi avrebbe avuto mio marito, se a 50 anni non fosse morto di mesotelioma».

C’è chi non ha attrattiva né per il cibo, lo stomaco è serrato da una morsa, né per sgranchirsi le gambe. E’ come se continuare a presidiare quel luogo laicamente sacro deputato a fare giustizia aumentasse il personale contributo fattivo alla causa.

«E pensare che tutto è cominciato quarant’anni fa – mormora Benedetto Terracini, nella postazione occupata all’inizio del pomeriggio -, allora non avevamo la minima idea dei processi…». Terracini è un «gigante» dell’epidemiologia piemontese e internazionale, uno degli scienziati protagonisti, fin dalla prima ora, della grande mobilitazione contro l’amianto. Lui evoca come tutto era cominciato. Ricorda l’allora giovane medico Corrado Magnani, «che lavorava all’Asl di Asti e aveva una approfondita competenza specifica nella misurazione delle fibre di amianto. Incontrò il medico casalese Massimo Capra Marzani, che aveva fatto una tesi sull’elevato numero di morti di amianto a Casale… Corrado me ne parlò…». Da lì cominciarono gli studi epidemiologici da cui, appunto, dal punto di vista scientifico «è cominciato tutto» per fare luce sul caso Casale.

DOPO IL PRANZO

A poco a poco ci sono i rientri, chi prende posto, chi torna a piazzare cavalletti e telecamere, il sindaco Riboldi, che era rientrato in municipio a Casale, torna a Novara e si siede accanto alla presidente dell’Afeva Giuliana Busto. Dice Riboldi: «La fascia tricolore che indosso rappresenta qui tutta la comunità casalese e soprattutto le vittime». E poi prendono posto i famigliari, che si guardano attorno nella speranza di catturare qualche stralcio di previsione rassicurante. Ricordano, si commuovono, sperano. «E se dovessero assolverlo come hanno chiesto i difensori?», «Vuoi dire? Ma dopo quello che abbiamo sentito?».

I legali di Schmidheiny avevano chiesto l’assoluzione del loro assistito «per mancanza di prova sul nesso di causalità», e hanno impostato la strategia difensiva soprattutto instillando il dubbio su determinate tesi scientifiche sostenute invece dall’accusa.

Il nervosismo cresce, anche tra magistrati e avvocati. Camminano su e giù, dentro e fuori, mettono e tolgono il bavaglino, indossano e sfilano la toga, abbozzano sorrisi striminziti.

Anche Stephan Schmidheiny, in questo momento, andrà su e giù per le stanze di casa sua, in apprensiva attesa di conoscere il proprio destino? L’ansia è democratica e universale.

Il brusio diffuso è inciso, ogni tanto, dal clac di una scatoletta di caramelle o dal suono di un cellulare improvvidamente non silenziato.

TRA UN’ORA

Gli occhi sono puntati sulla cancelliera: ogni volta che afferra il cellulare tutti si trattiene il fiato. Falso allarme. Ce ne sono più d’uno. Finché alle 17,10 è la volta buona: «La Corte esce tra un’ora» annuncia.

Ogni tanto cigolano delle porte in corridoio, si trattiene coralmente il respiro che, dopo qualche istante, torna a defluire accompagnato da scuotimenti del capo. «Ancora niente».

Finché, «ci siamo, ci siamo, arrivano».

La cancelliera va a controllare personalmente il microfono al centro, picchiettandoci sopra il polpastrello dell’indice. Cenno d’assenso con il tecnico.

ENTRA LA CORTE

Siamo pronti.

I giudici, alle 18,45, raggiungono la loro postazione elevata, si dispongono come in riga, al centro il presidente.

Tutti ci si alza in piedi, anche chi fatica e si regge al bastone. Il momento è sacro. Alle 18,46, Pezone inizia la lettura. Ogni respiro mette la sordina.

«In nome del Popolo Italiano, la Corte di Assise di Novara, ha pronunciato la seguente sentenza nella causa penale contro Schmidheiny Stephan Ernst. Visti gli articoli…». Chi ha un po’ di dimestichezza capisce e mormora: «E’ il preambolo della condanna».

Segue l’elenco di 392 nomi: quei nomi – per chi sa, per chi in questa storia ci è dentro in qualche misura di vicinanza – sono figure che sembrano di colpo apparire, proprio lì tra la folla assiepata, con sembianze e sguardi. Sono volti amici e amati. Si ingoia saliva, le lacrime per pudore rimangono sigillate dentro.

C’è chi rammenta che, nel 2012, al Maxiprocesso Eternit Uno a Torino, il presidente Giuseppe Casalbore pronunciò 2857 nomi: la lettura del dispositivo durò diverse ore, sempre in piedi. Qualcuno sorride ricordando: «Per resistere, facevo il passo dell’orso, dondolando e spostando il peso da un piede all’altro».

La voce di Pezone tradisce stanchezza, si assottiglia, talora gratta in gola, ma procede spedito, senza pause per 16 minuti.

Poi le parole finali: «L’udienza è terminata. Grazie a tutti». Sono le 19,02.

Ultimi saluti. I pm: «Il nostro impianto accusatorio ha tenuto. E’ stata riconosciuta la sussistenza degli omicidi, anche per i casi ambientali». Le parti civili. Laura D’Amico, che, tra gli altri, ha rappresentato Afeva: «Dopo anni e anni di impegno non si può che essere soddisfatti: questa sentenza afferma la fondatezza delle prove raccolte dalla procura. Finalmente un punto a favore della giustizia». Esther Gatti, patrono di diversi Comuni: «Giustizia è fatta, per ora. Ma si va avanti». Laura Mara, che ha tutelato Medicina Democratica: «Questa sentenza è un messaggio importante nel panorama giurisprudenziale italiano, un messaggio di speranza per tutti i procedimenti di amianto pendenti».

E’ importante sottolineare che i processi Eternit (Maxi e Bis), caratterizzati da una volontà tenace di magistrati, consulenti e collaboratori di approfondire e conoscere, hanno avuto il merito enorme di portare in luce una tragedia che, per anni, aveva confinato la sua drammaticità nel perimetro stretto della città di Casale. Senza i riflettori processuali, non sarebbe maturata una così diffusa sensibilità e, molto probabilmente, non sarebbero state attivate tante attenzioni e risorse per la ricerca medica e le bonifiche.

E poi un saluto ai difensori; si sono battuti con scrupolo e con indiscutibile competenza giuridica. Un sorriso stirato maschera a stento la loro delusione. E adesso? Possiamo dirci arrivederci? Di Amato e Alleva: «Arrivederci, sì certo arrivederci – annuiscono – : ci rivedremo in Appello».

SEI CONTENTA?

Appena terminata la lettura del verdetto, qualcuno mi chiede: «Sei contenta?». La domanda mi imbarazza. Non posso essere contenta che siano stati inflitti dodici anni di reclusione perché, indipendentemente dal quantum, rappresentano la conferma che sono stati commessi plurimi omicidi colposi e pluriaggravati di cui l’imputato è stato riconosciuto colpevole.

Tutto ciò a dire che a quel processo si è arrivati perché sono morte centinaia di persone. Non posso essere contenta di questa tragedia immane che si è abbattuta sulla mia città, Casale Monferrato, sventurata e coraggiosa; una tragedia che non è finita, perché ci sono molte altre vite sfregiate dal mal d’amianto, il mesotelioma. E li vedo, li conosco, di parecchi ho condiviso e condivido sofferenze, paure, rassegnazione, dignità e speranze struggenti. No, non posso essere contenta.

Nella notte che ha preceduto la giornata di mercoledì e nelle successive lunghissime ore di attesa trascorse in aula, mi sentivo aggrovigliata da una tensione incomprimibile. E, tuttavia, mentre l’animo era scosso dall’ansia potente, la coscienza era tranquilla. Ma questi sentimenti non confliggevano, anzi.

Non posso essere contenta, ma la coscienza, sì, è tranquilla di aver fatto tutto quel che si è potuto. In molti lo hanno fatto. In molti hanno fatto, per il proprio ruolo, tutto quello che hanno potuto scoperchiando e rendendo visibile un disastro umano e ambientale che è casalese, ma che si ripropone in più parti del mondo; si sono presi a cuore questa causa disperata, dando un senso al dolore immane e ingiusto dei malati e dei loro famigliari. Parlo dell’impegno di magistrati tenaci, consulenti e collaboratori, avvocati, medici e loro assistenti, scienziati e ricercatori, attivisti e sindacalisti, giornalisti e divulgatori, amministratori pubblici di tutte le epoche, insegnanti e studenti.

Alla fine l’impegno corale si è concretizzato in un verdetto che ha un alto significato di giustizia: è stato acclarato in una sentenza, «pronunciata nel nome del Popolo Italiano», che questa collettività ha subito un torto (grave come la morte, tremendo come la sofferenza di chi resta, angosciante per la paura che tutti abbiamo di ammalarci di mesotelioma) e che qualcuno questo danno lo ha commesso. Questo qualcuno ha un nome: Stephan Schmidheiny.

Ci siamo ribellati a un torto, con compostezza e rispetto abbiamo posato quel dramma sull’altare laico della Giustizia e, finalmente, questo principio di responsabilità è stato sancito. Questo ci dà la consapevolezza di essere nel giusto, ci dà un po’ di pace e ci apre la strada della pacificazione. Che, continuo a ripeterlo finché avrò voce, troverà compimento soltanto con un atto concreto di giustizia riparativa da parte di Stephan Schmidheiny.

La parola «contenta» non è adeguata. Ma sollevata sì, lo sono, e orgogliosa della mobilitazione collettiva che ha portato a questo risultato, da cui è esente qualsiasi vocazione forcaiola.

E nella gente, quella per la quale si è fatto questo processo, ho colto un senso di consolazione che un poco lenisce la consapevolezza che nulla potrà restituire chi è mancato.

L’impianto accusatorio ha tenuto, anche se i giudici hanno attribuito all’imputato un profilo psicologico diverso da quello contestato. Ha retto, però, il nesso causale non soltanto per gli ex lavoratori, ma anche per i cittadini vittime di esposizione ambientale, che sono ormai la maggior parte. Riflessioni più approfondite sono rimandate alla lettura delle motivazioni.

Ma fin da ora, un magistrato di grande autorevolezza come Giancarlo Caselli, che bene conosce le vicende processuali dell’Eternit, in un’analisi pubblicata su La Stampa (9 giugno 2023) ha definito questa sentenza, pur ancora di primo grado, «una pietra miliare del percorso verso una nuova sensibilità e cultura, sul piano della tutela investigativo-giudiziaria, di quei fondamentali diritti dei cittadini che sono la sicurezza sul lavoro e la salute».

UNA NUOVA VIA, NOBILE E POSSIBILE

Il 7 giugno si è concluso un capitolo, ma il processo avrà altre tappe (Appello, Cassazione…). In più, però, potrebbero esserci ulteriori processi penali o civili a carico dell’imprenditore svizzero settantaseienne; infatti, oltre alle 392 vittime elencate nel capo di imputazione dell’Eternit Bis, ci sono stati nuovi malati, nuovi morti per i quali chiedere giustizia.

Forse è venuto il momento per Schmidheiny di pensare che esistono altre strade da percorrere: la più nobile è quella di finanziare e coordinare la ricerca di una terapia per il mesotelioma, fino a che la cura non sarà trovata. Compri una casa farmaceutica, signor Schmidheiny, ha la forza economica per farlo, prenda questa decisione e, da imprenditore quale lei è, investa le risorse che servono – ingaggiando ricercatori autorevoli, capaci e indipendenti, in tutto il mondo – per questo obbiettivo salvifico. E’ questa la via della giustizia riparativa, antitesi della vendetta. E’ la sua unica possibilità di riscatto etico e umano. E quando si troverà quella medicina allora, sì, sarò contenta. Tanto contenta.

«A un tal dubbio, a un tal risico, gli venne addosso una disperazione più nera, più pesante, dalla quale né pur colla morte si poteva fuggire (…). Tutto ad un tratto gli si levarono nella memoria parole che aveva intese e rintese poche ore prima: — Iddio perdona tante cose per una opera di misericordia! — E non gli tornavano già con quell’accento di umile preghiera con che erano state proferite; ma con un suono pieno d’autorità, e che insieme induceva una lontana speranza. Fu quello un momento di sollievo (…)». [Alessandro Manzoni, I Promessi Sposi, Capitolo XXI, la notte dell’Innominato]

[Al fondo sono pubblicate alcune fotografie riferite all’udienza del 7 giugno 2023]

TRANSLATION by VICKY FRANZINETTI

… and the tormented self examiner so as to account for this one fact, found himself involved in the examination of his whole life. Back he went, from feud to feud, from murder to murder, from crime to crime; each one of them came back to his new conscience isolated from the feelings that had made him want to commit them, so that they reappeared in all the monstrousness which those feelings had prevented him noticing. (…) – by Alessandro Manzoni, The Betrothed, Chapter XXI, The Unnamed – translated by Archibald Colquhoun, published by JM Dent & sons LTD London 1951

June the 7th Eternit bis hearing –

Chronicle of a long wait

By Silvana MOSSANO

Stephan Schmidheiny, Eternit’s last surviving owner, was convicted: he was found guilty of multiple manslaughter, aggravated ‘by having committed the act in violation of the rules for the prevention of accidents at work’ and also ‘by having acted despite knowledge of the event[1].

The Court of Assizes of Novara, in the University’s Lecture Hall where the Eternit Bis trial was held, sentenced the defendant to 12 years’ imprisonment. The prosecution had filed for murder but the court reduced the charge to manslaughter (wilful and with aggravating circumstances). This resulted in the statute of limitations being applied to a number of cases.

Let us analyse the verdict carefully –the court’s motivations will be given in 90 days. There is a first group of victims (147 in all) for whom the defendant was sentenced to 12 years; this group, in turn, is divided into a subgroup A (9 victims) for whom Schmidheiny was charged with both aggravating circumstances (violation of the rules of prevention and wilful negligence) and a subgroup B (138 victims) for whom he was charged only with the aggravating circumstances .

There is another group of victims (199 in all) for whom the statute of limitations applied. When does the statute of limitations apply? In cases where at least 15 years have passed since the date of death. This means that the 199 victims in this second group have been dead for more than 15 years. Another question: as for these 199 prescription barred cases, is Schmidheiny guilty? According to Italy’s procedural law, if the court deems the defendant innocent, even when an offence is prescription-barred, the judge does not simply declare ‘not to proceed due to the statute of limitations’, but must specifically issue a sentence of acquittal using the formula ‘because the fact does not exist’ or ‘for not having committed the fact’. However, this was not the case for these 199 deaths. The verdict implies that there was evidence that would have led the court to issue a sentence of conviction for the death penalty against this group as well, had the statute of limitations not applied.

On the other hand, the judges recognised that there was no evidence to convict in the case of 46 other victims, and for these the defendant was acquitted. The grounds for the verdict, which will be filed within 90 days, will explain whether the decision in these cases is to be attributed to uncertain diagnoses or to the difficulty of associating the disease with a precise period of the victims’ lives in Casale.

The defendant is also banned from public office for five years, and] has also been sentenced to pay compensation in separate civil lawsuits to various parties including the national government, the Piedmont Region, the Province of Alessandria and the Municipality of Casale Monferrato. The Court ordered Schmidheiny to immediately pay enforceable provisional compensation to a long list of entities, trade unions, associations and individual injured parties. The largest sums awarded by the court were to the Municipality of Casale (EUR 50 million), the Prime Minister’s Office (EUR 30 million) and AFeVA (half a million). In total, more than € 86 million, plus the obligation to pay the costs of the constitution of civil parties for an amount exceeding EUR 200,000. (TN: However, similar sums awarded in previous cases were never paid)

Thus ended, on Wednesday 7 June, the trial of the Eternit Bis trial in the Court of Assizes, after 42 hearings over two years, starting on 9 June 2021.

June 7 EARLY IN THE MORNING

At 8.15, the courtroom is empty, the lights are low, the atmosphere subdued. There is only the sound engineer testing the system, wandering around the various stations, checking that everything is in order. It is a historic day. In two years we got to know each other. We say goodbye, it’s a bit of a farewell: ‘It’s the last time we’ll meet…’.

I take my seat in the chair occupied since the first hearing, the bag at my side, with the notebook for notes, something to read during the breaks, a pen, and a spare one, just in case.

Outside, the first activists set the scene, they have done so, tirelessly, at the beginning of every hearing: the nation’s white red and green flag hangs from the barriers and walls with the words Eternit Giustizia, and the yellow ones of Legambiente (the environmentalists), those of Medicina Democratica and Aiea, as well as those of the various trade unions, the placards from the students’ work, even those who recently took part in the environmental competition ‘Premio Guglielmo Cavalli’, in honour of a trade unionist who died of asbestos. In the foreground, a long, new, blue banner: it is a reproduction of the base of the Eternot Flower Nursery Monument, which stands in Casale in the park built on the former site of the Eternit plant, in the Ronzone District. Printed on it is the phrase: ‘The handkerchiefs soaked in our tears will put on wings and fly far away to find deep roots of justice’.

Slowly, the first lawyers arrive in the courtroom; journalists with camera crews, both Italian and foreign, compete for the best positions where they can set up their camera stands. Then the prosecutors, with their staff and consultants, other lawyers for the defence and civil parties, family members of the victims, trade unionists and health workers who have courageously accompanied so many patients in illness, activists, many arrived by special bus or in a procession of cars. They have also mobilised from the US, France, Holland, Switzerland, Spain. There is much animation, amid a flutter of togas and whispers.

THE COURT ENTERS

Then the judges arrive: President Gianfranco Pezone and his colleague Manuela Massino put on their bibs and togas, the (six) members of the jury place their tricolour sashes over their shoulders. At 9.30, the roll-call begins, one name after another. “Have I called everyone? Good.”

Wednesday June the 7th is, yes, the hearing of the verdict, but there is still room for replies; it is true that all the parties had been invited to file them in writing by mid-May, but the Prosecution is determined to put its case forward till the last possible minute. Dr Gianfranco Colace almost says this to himself: ‘This is too important and delicate a trial, we cannot assume that we have exhausted every argument… maybe we have not said everything, maybe we still need to point out…’. And he details. He dwells on the dust, it is “a” culprit, but it is not “the” culprit’; but, in the prosecution’s opinion, the most conspicuous factor was the intense and uncontrolled activity of the plant and the failure to apply the measures that should have contained the dust. Certainly, the dust was dangerous, so much so that Eternit’s top management, at one point during Stephan Schmidheiny’s ten-year tenure, allegedly warned the company Bagna, the waste disposal contractor, to stop distributing it to citizens who requested it. This warning was not confirmed by the contractor, but, if true, ‘the population, on the other hand,’ Colace emphasises, ‘was never given any information about the serious danger of this material. Plaintiffs’ lawyer Esther Gatti concludes: ‘Where was the label stating ‘Asbestos may seriously damage your health? We have never seen it!”.

On the fact, referred to by the defence, that the processing of asbestos was a lawful activity in Italy until 1992 (thus beyond the 1976-1986 decade of Schmidheiny’s management), ‘nothing to object to,’ commented the Prosecutor, ‘but a lawful activity must be carried out lawfully! There were rules to comply with, but they were not observed, as proved by the dozens and dozens of fines imposed by the labour inspectors and monitoring agencies.

“Asbestos kills,’ Dr Colace remarked, ‘Schmidheiny personally had all that knowledge. He knew it, he knew it, and he went ahead anyway, at the cost of causing the damaging event’. The deaths.

Prosecutor Dr Mariagiovanna Compare insists on the certainty of the diagnoses, queried by the defence. “They were mesotheliomas,” she points out, “and it has been excluded with certainty that other diseases were not the cause of death. She strongly reiterates ‘the thesis, prevailing in scientific circles, of the relevance of the cumulative dose of exposure’, as illustrated and argued by the consultant Prof Corrado Magnani, ‘whose authority and independence of judgement is established’.

For the civil parties, lawyer Maurizio Riverditi states: ‘This trial proved that, faced with the doubt that people could die, Schmidheiny did not consider stopping the production but decided to continue with the use of asbestos’. Then looking at the judges one by one: ‘If one of the 392 victims was a family member of yours, you would call the defendant a murderer’. Lawyer Esther Gatti, representing the Municipality of Casale, spoke on the compensation claims. Mayor Federico Riboldi, present at the hearing, leant forward so as not to miss a word. The lawyer says: ‘We have asked for 50 million in compensation and litigating the defence challenges our request because they say it refers to damage under the statute of limitations and, in addition, that it cannot be linked to the deaths. Many of the reclamation expenses were incurred after the statute of limitations pronounced by the Supreme Court in 2014 for the Eternit One Maxi-trial where the charge was creating an environmental disaster. Moreover, our claim for compensation is, yes, attributable to the deaths precisely as they were caused by the defendant’s conduct”.

THE DEFENCE

Defence attorneys Dr Astolfo Di Amato and Dr Guido Carlo Alleva asked for a five-minute recess. They did not expect to present extensive oral replies. They returned and referred to the written reports they had filed at the time, insisting on a couple of points. “Here it is said that Schmidheiny knew; but how: Did Schmidheiny know more than the inspectors and scientists? Not one of them ever said that the work should be stopped! Only at the 1997 Scientific Consensus was it definitively stated that it was not possible to work with asbestos safely. 1997, eleven years after the closure of the Casale plant. Before that it was believed it could go on’. Dr Alleva, while recognising ‘the dramatic nature of this affair from the human point of view’, insists that ‘we cannot deny history: we must place ourselves there, between 1976 and 1986, and take into account the knowledge of the time. Otherwise, it is an overkill, an injustice’.

Silence. No one asks to speak any more. The President: ‘with this the hearing is over and we withdraw to chambers. Before the court retires to the council chamber to decide the verdict, Judge Pezone addresses the audience: On my own behalf and on behalf of the court, ‘I wish to express a great thanks to all the trial parties for the attention and skill with which you have dealt with such complex issues and for the fairness of the discussion. Gratitude also goes to the institutions of Novara and the University Chancellor.

The Court rises, Dr Pezone says that “it will take some time”: he will inform the clerk at least an hour before the time when the final decision will be read out.

At 11.30 a.m. the court withdraws. The wait will last seven and a quarter hours.

PREDICTIONS AND SUPERSTITION

As the judges leave, the motley crowd melts and comes alive. In the corridors and outside (in the courtroom no, it is forbidden), journalists hunt for interviews, and interviewees are tugged from microphone to camera relentlessly. Others scatter, some to eat in the canteen (‘mhm, it’s not so good…’) others to bars and clubs not far away. A few, very few, remain in the hall. Someone whispers: ‘What do you think? How do you think they will decide?’ But no one gives in to the hazard of making predictions, for fear of being proved wrong. A few vague hypotheses hover, ‘if they decide this way… if they should take into account…’. It is better to keep quiet out of superstition. Some university students look on uncertainly. “We are not Law students, we are from Economics,’ they clarify, a little intimidated, ‘but we would like to understand…’. They cross paths with Assunta Prato, asbestos widow; and she explains with simplicity and clarity, as if they were her pupils. The boys widen their eyes: ‘We are here, in Novara, not far from Casale, but we know nothing about this: yes, we had heard of asbestos, but that it was so dangerous… deadly…’. They are shaken, a veil is torn. “But how old is the defendant?” Assunta says: ‘Seventy-six, the same age my husband would be today, had he not died of mesothelioma at 50’.

There are those who want no food, their stomachs are closed, nor do they want to stretch their legs. It is as if continuing to preside over that secularly sacred place deputed to do justice increases one’s personal contribution to the cause. ‘And to think that it all started forty years ago,’ murmurs Prof Benedetto Terracini, in the seat he took at the beginning of the afternoon, ‘back then we had no idea about trials…’. Terracini is a ‘giant’ of Piedmontese and international epidemiology, one of the leading scientists in the great mobilisation against asbestos from the very first hour. He recalls how it all began. He recalls the then young doctor Corrado Magnani, ‘who worked at the Health Service of Asti and had in-depth expertise in measuring asbestos fibres. He met the Casale doctor Massimo Capra Marzani, who had done a thesis on the high number of asbestos deaths in Casale… Corrado told me about it…’. From there began the epidemiological studies from which, precisely, from a scientific point of view ‘everything started’ to shed light on the Casale case. ‘Nothing would have happened,’ adds Terracini, ‘without the support of the then regional councillor for health, Sante Baiardi, who is still alive at the age of 97’.

AFTER LUNCH

Little by little people dribble in, those who take their seats, those who return to set up tripods and cameras, Mayor Riboldi, who had returned to the town hall in Casale, returns to Novara and sits next to Afeva President Giuliana Busto. Riboldi says: “The sash I wear here represents the whole Casale community and above all the victims”. And then the family members take their seats, looking around in the hope of catching some glimpse of a reassuring forecast. They remember, they are moved, they hope. “What if they acquit him as the defenders have asked?”, “You mean? But after what we have heard?”Schmidheiny’s lawyers had asked for the acquittal of their client ‘for lack of proof on the causal link’, and had set up their defence strategy mainly by instilling doubt on certain scientific theses supported by the prosecution. Nervousness grows, even among magistrates and lawyers. They walk up and down, in and out, put on and take off their bibs, put on and take off their robes, sketchy smiles. Will Stephan Schmidheiny too, at this moment, be pacing up and down the rooms of his mansion, apprehensively waiting to know his fate? Anxiety is democratic and universal.

The buzz of whispers is interrupted, every now and then, by the rustle of a candy box or the sound of an unmuted mobile phone.

IN AN HOUR

All eyes are on the court clerk: every time she grabs her mobile phone, everyone holds their breath. False alarm. There are more than one. Until 5.10 p.m.: ‘The Court will be out in an hour,’ she announces. From time to time, doors creak in the corridor, breaths are chorally held, which, after a few moments, flow out again accompanied by shaking of the head. “Still nothing.” Until, ‘here we go, here they come’. The court clerk goes to personally check the microphone in the centre, tapping the fingertip of her index finger on it. She nods in assent to the technician.

THE COURT ENTERS

We are ready. At 6.45 p.m., the judges sit in a row, the president or Chief Justice at the centre. Everyone stands up, even those who struggle and hold on to their sticks. The moment is sacred. At 18.46, Pezone begins the reading. Everyone holds their breath.

“In the name of the Italian People, the Novara Assize Court has pronounced the following sentence in the criminal case against Schmidheiny Stephan Ernst. Having regard to the articles…”. Those with some familiarity understand and murmur: ‘It is the preamble to the verdict. Then follows the list of 392 names: those names – for those who know, for those who are in this story to some degree of proximity – are figures who suddenly seem to appear, right there in the thronged crowd, with looks and glances. They are friendly and beloved faces. One swallows saliva, tears shyly remain sealed inside. Some remember that, in 2012, at the Eternit One Maxi-trial in Turin, the late Judge Giuseppe Casalbore pronounced 2857 names: the reading of the judgment lasted several hours, all this time the judges and the audience remaind standing. Someone smiles remembering: ‘To resist, I used to do the bear’s step, swinging and shifting my weight from one foot to the other’. Pezone’s voice betrays fatigue, thinning, sometimes scratchy in the throat, but he proceeds swiftly, without pause for 16 minutes. Then the final words: ‘The hearing is over. Thank you all’. It is 7.02 p.m.

Final greetings. The Prosecutors: ‘Our indictment held. The existence of the murders has been recognised, including the environmental cases”. The plaintiffs’ lawyer Laura D’Amico, who, among others, represented Afeva: ‘After years and years of commitment, we can only be satisfied: this ruling affirms the soundness of the evidence gathered by the prosecution. Finally a point in favour of justice’. Lawyer Esther Gatti: ‘Justice is done, for now. But we are moving forward’. Lawyer Laura Mara, who defended Medicina Democratica: ‘This ruling is an important message in the Italian legal landscape, a message of hope for all pending asbestos trials.

It is important to emphasise that the Eternit trials (Maxi and Bis), characterised by the tenacious will of magistrates, consultants and collaborators to investigate and learn, have had the enormous merit of bringing to light a tragedy that, for years, had confined its dramatic nature to the narrow remit of the city of Casale. Without the trial spotlight, such widespread sensitivity would not have matured and, most likely, so much attention and resources for medical research and reclamation would not have been activated. And then we must salute the defence lawyers; they fought with scrupulousness and unquestionable legal competence. A stretched smile barely masks their disappointment. And now? Can we say goodbye? Drs Di Amato and Alleva: ‘Goodbye, yes of course goodbye – they nod – : we will meet again at the Appeal’.

ARE YOU CONCERNED?

As soon as the reading of the verdict is over, someone asks me: ‘Are you happy?’ The question embarrasses me. I cannot be happy that twelve years’ imprisonment has been given, regardless of the length, it represents confirmation that multiple manslaughter and aggravated murder were committed of which the defendant was found guilty. All this is to say that this trial came about because hundreds of people died. I cannot be happy about this terrible tragedy that has befallen my town, Casale Monferrato, hapless and brave; a tragedy that is not over, because there are many other lives scarred by asbestos disease, mesothelioma. And I see them, I know them, of several I have shared and share suffering, fears, resignation, dignity and poignant hopes. No, I cannot be happy. In the night leading up to Wednesday and in the subsequent very long hours of waiting in the courtroom, I felt twisted inside. And yet, while my soul was shaken by powerful anxiety, my conscience was calm. But these feelings did not conflict, on the contrary. I cannot be happy, but the conscience, yes, is calm that one has done all one could. Many did. Many have done, in their own role, all they could by uncovering and making visible a human and environmental disaster that is of Casale, but which recurs in many parts of the world; they have taken this desperate cause to heart, giving meaning to the immense and unjust pain of the sick and their families. I am talking about the commitment of tenacious magistrates, consultants and collaborators, lawyers, doctors and their assistants, scientists and researchers, activists and trade unionists, journalists and popularisers, public administrators of all ages, teachers and students.

In the end, the general commitment was transferred into a verdict that means justice: it was ascertained in a sentence, ‘pronounced in the name of the Italian people’, that this community had suffered a wrong (as serious as death, as tremendous as the suffering of those left behind, as distressing as the fear we all have of falling ill with mesothelioma) and that someone had committed a crime, damaged us. This someone has a name: Stephan Schmidheiny.

We rebelled against a wrong, with composure and respect we laid that tragedy on the secular altar of Justice and, finally, this principle of responsibility has been sanctioned. This gives us the knowledge that we are in the right, gives us some peace, and opens the way to peace-making. Which, I keep repeating as long as I have a voice, will only find fulfilment with a concrete act of restorative justice on the part of Stephan Schmidheiny. The word ‘pleased’ is not adequate. But relieved yes, I am, and proud of the collective mobilisation that led to this result, from which any [?? gallows vocation] is exempt. I perceived a sense of relief in the people, the ones for whom this trial was held, soothing the awareness that nothing will be able to return those who have died.

The indictment held, even though the judges attributed a different psychological profile to the defendant. It held, however, not only for the former workers, but also for the victims of environmental exposure, who are now the majority. More in-depth reflections are postponed to the reading of the court’s motivations. As of now, a magistrate of great authority such as former Chief Mafia Prosecutor and Judge Giancarlo Caselli, who is well acquainted with the Eternit trial events, in an analysis published in La Stampa (9 June 2023) defined this sentence as ‘a milestone on the path towards a new sensitivity and culture, in terms of investigative-judicial protection, of those fundamental rights of citizens that are safety at work and health’ even though it can be appealed.

A NEW WAY, NOBLE AND POSSIBLE

On 7 June, one chapter ended, but the trial will have other stages (Appeal, Cassation…). In addition, however, there could be further criminal or civil trials against the 76-year-old Swiss entrepreneur; in fact, in addition to the 392 victims listed in the Eternit Bis indictment, there have been new sick people, new deaths for whom justice must be sought. Perhaps the time has come for Schmidheiny to think that there are other paths to take: the noblest is to finance and coordinate research into a therapy for mesothelioma, until a cure is found. Buy a pharmaceutical company, Mr. Schmidheiny, you have the economic strength to do so, make this decision and, as the entrepreneur that you are, invest the necessary resources – by hiring authoritative, capable and independent researchers – to save lives. This is the path of restorative justice, the antithesis of revenge. It is its only chance for ethical and human redemption. And when that medicine is found then, yes, I will be happy. So happy.

At such a doubt , at such a risk, a blacker, deeper despair came over him, a despair from which there was no escape, – not even in death. He let his weapon drop, and began clawing his hair, his teeth chattering, trembling all over. All of a sudden the words he had heard repeated again and again a few hours before came back to his mind: – God forgives so much for a deed of mercy! And they no longer came back to him in those accents of humble supplication in which they had been uttered, but with a tone of authority, which induced at the same time a far-away hope. That was a moment of relief (…)Alessandro Manzoni, The Betrothed, Chapter XXI, The Unnamed – translated by Archibald Colquhoun, published by JM Dent & sons LTD London 1951

[1] (per )aver commesso il fatto con violazione delle norme per la prevenzione degli infortuni sul lavoro» e anche «dall’aver agito nonostante la previsione dell’evento

Leggo la notizia e mi emoziono. È duplice l’emozione: da una parte rende corpo dalla constatazione che, almeno in parte, la giustizia ha preso la mano dei casalesi e di tutti quanti hanno guardato al processo con la speranza nel cuore. Dall’altra una stretta al cuore per il pensiero che tra tutte quelle persone che hanno tanto sofferto ci siano soggetti di serie A e altri di serie B, che non saranno trattati allo stesso modo… Gioisco con tutti voi per questo risultato che mi pare abbia aspetti “storici” che ancora una volta mettono Casale in primo piano nella terribile lotta contro l’amianto. Un abbraccio a tutti i Casalesi.

Un accorato GRAZIE SILVANA . Per averci accompagnato in questi lunghi anni con il puntuale e chiaro resoconto sul processo Eternit bis . Non siamo “contenti” ma un tassello di verità ha messo la parola “ fine “per ora a questo doloroso momento attraversato da chi viveva e vive sul nostro territorio. GRAZIE A TUTTI !!!

Mille grazie Silvana!

È ben più di una cronaca anche questo tuo resoconto!

Certamente possiamo dire che questa tappa è stata vinta. Infatti di grande rilevanza, non solo da noi , è l’aver visto respinte sostanzialmente tutte le tesi difensive, di cui ricordiamo la tristezza, a volte anche la rabbia, quando le abbiamo ascoltate in aula.

Altrettanto certo è che questa triste “corsa” non è finita qui: la durissima scalata sulla montagna della Giustizia è ancora lunga e in cima a questa vetta, in processi simili a questo nel mondo, nessuno è ancora giunto

Dopo la Corte d’Appello, la Cassazione ma non sappiamo ovviamente quando. E con la riqualificazione del reato da omicidio Volontario con dolo eventuale a Colposo aggravato, ricompare sulla scena l’incombenza della prescrizione.

Ciò per noi di infausta memoria e dunque ripetiamo che sarebbe davvero ora che il potere legislativo e lo Stato,mettessero in atto le norme e l’organizzazione necessaria per non giungere alla dichiarazione di fallimento della Giustizia e alla beffa per le vittime,spazzando via anni e anni di prezioso ed enorme lavoro….

Vero, come ribadisci Silvana, Smidhainy avrebbe dovuto pensarci sopra molti anni fa per riparare i danni. Oggi, anche se con un iritardo molto colposo e visto che si dichiara un filantropo, dimostri che ha compreso finalmente la tragedia spendendo un po delle sue ricchezze per la ricerca per sconfiggere il mesotelioma. Mesotelioma che purtroppo ancora imperversa nel mondo, anche per il suo amianto.

Teniamo duro! Andiamo avanti! Si aggiunge sempre qualcuno a ricordarcelo.

Certo, è stato condannato ma con una pena oserei dire troppo leggera. I cavilli della magistratura a volte permettono queste sentenze.

Però è una grande soddisfazione aver lottato contro un mostro di quella portata. Dobbiamo essere orgogliosi comunque.

Forza Casale. Non arrendiamoci.

Grazie Silvana per le dettagliate informazioni.

Brava Silvana! Grazie per il nuovo preciso, completo e coinvolgente resoconto. Un aggiornamento che sentiamo nostro e possiamo solo immaginare quanto sia sentito per te. L’auspicio, aldilà delle strade legali ancora da percorrere, è proprio quello che hai indicato tu: che questo moderno innominato trovi un’occasione per mostrare un segno di quella moralità che il suo collegio difensivo, dopo tanti anni, non è riuscito a far vedere.

Grazie mia cara dolce e forte amica, tanto dolore abbiamo vissuto in questa città…tanto dolore ancora si vivrà…la tua preziosa e puntuale rendicontazione dei processi ci ha consentito di essere Casalesi sempre presenti ai passi processuali…a farci sperare che giustizia venisse fatta….ma come tu giustamente affermi …come si può essere contenti…con tutti gli amici e parenti che per causa dell’amianto non ci sono più…certo la sentenza è molto importante…ma non basta….grazie ancora Silvana

I was deeply moved by the report by Silvana of what transpired in the courtroom in Novarro on June 7. The small details of the long wait, the dissection of the judgment, the role of various actors and the personal impact on her and other Casalesi of the long fight for justice brought to life for those of us not present the sheer drama and import of the decision. Thank you SIlvana.

I was deeply moved by the report by Silvana of what transpired in the courtroom in Novarro on June 7. The small details of the long wait, the dissection of the judgment, the role of various actors and the personal impact on her and other Casalese of the long fight for justice brought to life for those of us not present the sheer drama and import of the decision. Thank you SIlvana.