Signor Stephan Schmidheiny, il suo avvocato ha affermato, con molta onestà, che la comunità casalese, esemplare e moralmente integra, ha subito e sta subendo una tragedia. Non pensa, signor Schmidheiny, che sia giunto il momento, indifferibile, di assumere direttamente e personalmente, da imprenditore filantropo, il coordinamento e il finanziamento di una ricerca seria ed efficace che produca al più presto una cura per guarire tutti i malati di mesotelioma del mondo?

REPORTAGE udienza 4 dicembre 2024

PARLA LA DIFESA

RIEPILOGO

* Tragedia con migliaia di morti

* Le forzature non producono giustizia

* La consapevolezza

* Investimenti e interventi

* Responsabilità del vertice e manutenzione carente

* La città «imbottita» di amianto: polverino e battuti

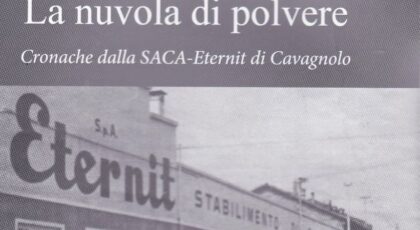

* Ma perché l’Eternit fallisce?

* Nascondimento del massimo livello

* Unico processo penale al mondo

PUNTO PER PUNTO

TRAGEDIA CON MIGLIAIA DI MORTI

«Quella che ha colpito la città di Casale è una tragedia per le migliaia di morti determinate da una malattia terribile. Terribile, sì, si muore soffocati. Questa tragedia ha colpito una comunità esemplare. E’ una ventina d’anni (a partire dall’inchiesta del Maxiprocesso Eternit 1, ndr) che li incontriamo e l’unica esternazione nei nostri confronti è la manifestazione di rispetto per il ruolo che svolgiamo. Una comunità il cui denominatore comune è quello della integrità morale. Quando, in quest’aula, è stata ricordata la signora Romana, be’, sono orgoglioso di averla conosciuta».

Ha iniziato così l’avvocato Astolfo Di Amato, difensore, insieme al collega Guido Carlo Alleva, dell’imprenditore svizzero Stephan Schmidheiny, chiamato a rispondere, davanti alla Corte d’Assise d’Appello di Torino, dell’omicidio volontario (con dolo eventuale) di 392 casalesi morti di mesotelioma, il mal d’amianto.

Dopo le requisitorie dei pubblici ministeri (Sara Panelli, Gianfranco Colace, Mariagiovanna Compare) e gli interventi dei legali di parte civile (tra gli altri, Laura D’Amico, Maurizio Riverditi, Giacomo Mattalia, Esther Gatti, Laura Mara, Alberto Vella, Alessandro Mattioda), ora tocca alle difese.

Avevano iniziato già il 27 novembre, con alcune considerazioni preliminari. Nell’udienza di mercoledì 4 dicembre, sono passati a esaminare le questioni di merito. La prima parte è stata svolta dall’avvocato Di Amato; mercoledì 11 dicembre, completerà l’avvocato Alleva.

Dunque, una tragedia. Non c’è su questo punto – e non potrebbe esserci – contrapposizione di vedute tra le parti: lo stillicidio terribile e doloroso di morti di mesotelioma è cominciato molti anni fa e continua.

E anche la considerazione successiva è ampiamente condivisa: «Una tragedia che colpisce una comunità dall’integrità esemplare necessita di giustizia» ha affermato Di Amato.

LE FORZATURE NON PRODUCONO GIUSTIZIA

Ma, «nel dare una risposta di giustizia, bisogna fare attenzione alle forzature; altrimenti che giustizia è?». Il senso di questa domanda per il legale si traduce così: volere a tutti i costi la condanna dell’imputato Stephan Schmidheiny è una vera risposta di giustizia? Domanda retorica che, per la difesa, racchiude già la risposta: no. E perché? La spiegazione è sintetizzata nel passaggio finale dell’arringa dell’avvocato Di Amato: «Schmidheiny non è un mascalzone. Schmidheiny è “figlio” di quel tempo (40-50 anni fa: fu a capo dell’Eternit tra il 1976 e il 1986, ndr). Attenendosi al sapere e al supporto tecnico dell’epoca, era fiducioso di poter utilizzare l’amianto in modo controllato. Poi, sì, è stato smentito, perché le morti sono continuate, ma le conoscenze di allora non consentivano ancora di sapere che non c’è soglia minima che elimini il rischio di ammalarsi di mesotelioma. Si è saputo soltanto negli anni Novanta». Ha insistito il difensore: «La condotta dell’imputato non ha violato le norme». Tanto più, ha rimarcato, che «il territorio casalese era letteralmente “imbottito” di amianto, ma non per colpa di Schmidheiny; era accaduto prima del suo arrivo nel 1976».

E da questo punto in poi le argomentazioni divergono rispetto a quelle della procura e delle parti civili, ma anche della sentenza di primo grado della Corte d’Assise di Novara, che ha condannato l’imputato a 12 anni di reclusione per l’omicidio colposo (e non doloso come sostengono i pm) di 147 vittime, ha prescritto per 199 casi e ha assolto per 46.

LA CONSAPEVOLEZZA

La difesa non nega che l’imputato conoscesse i rischi dell’amianto, ma non nella gravità con cui si è imparato a conoscerli successivamente al 1986 e, ancor più, negli anni Novanta.

Però, ci sono i verbali del Convengo di Neuss, da cui emerge la precisa consapevolezza dell’imputato di come e quanto l’amianto fosse nocivo. E ci sono le dichiarazioni virgolettate di Schmidheiny. «To be or not to be?» fu la domanda amletica che si pose, a dire «bisogna continuare a usarlo o smettere del tutto», sapendo che causa il mesotelioma? Scelse «to be», cioè continuare. E, ancora, è sempre Schmidheiny a parlare: «Dobbiamo ottenere il miglior risultato con il minimo sforzo». Secondo l’accusa è una affermazione indicativa della volontà di sfruttare l’attività il più possibile spendendo il meno possibile in sicurezza. Per la difesa, invece, la posizione dell’imputato all’epoca era questa: «E’ importante che subentri un cambiamento di mentalità di tutti. La stella polare dell’attività non può essere solo la produttività, ma anche il rispetto della salute e dell’ambiente». Era dunque questa l’intenzione di Schmidheiny al convegno di Neuss, e, soprattutto, pochi mesi dopo, quando diramò il manuale Auls cui attenersi scrupolosamente nel dare informazioni sull’amianto (ai lavoratori, ai loro famigliari, a sindacalisti, giornalisti, amministratori pubblici)? Come disse l’avvocato Maurizio Riverditi, di parte civile, «non si può entrare nella testa dell’imputato; per capire che cosa aveva in mente bisogna analizzare i fatti». Per il difensore Di Amato questa analisi dei fatti è riconducibile all’intenzione di «rispettare le regole, se qualcuno si lamenta fatelo parlare con i lavoratori e, se non è comunque convinto, date le risposte indicate in Auls». Anche perché, osserva Di Amato, «per dare un’informazione corretta non è obbligatorio choccare!». Vocabolo che era emerso proprio nei verbali di Neuss, documentando qual era stata la reazione dei 35 massimi dirigenti convocati dall’imprenditore svizzero quando aveva illustrato nocività e rischi mortali dell’amianto: erano rimasti «choccati».

Dismettere l’amianto era comunque difficile. Il difensore ha sottolineato che, nel 1982, non si era ancora pronti a sostituirlo ad esempio nella fabbricazione dei tubi per le condotte perché non c’erano altri materiali che «potessero reggere la pressione». Inoltre, Di Amato ha richiamato la posizione di Irving Selikoff, che alla Conferenza internazionale di New York nel 1964 aveva lanciato l’allarme sulla pericolosità dell’amianto, causa del mesotelioma non soltanto per chi lo lavorava. Ma, ha evidenziato il legale, «in un’intervista rilasciata al New York Times nel 1976, lo scienziato affermava che “il divieto dell’amianto non è necessario”», cioè, riassume il difensore, «se ne poteva fare un uso controllato».

Questa era, dunque, secondo la difesa, la reale consapevolezza dell’imputato tra il 1976 e il 1986. E, anzi, poiché negli stabilimenti italiani l’approccio agli adempimenti tecnici, certo, di sicurezza era carente rispetto a quello che già avveniva negli stabilimenti svizzeri, Schmidheiny mise a disposizione il laboratorio di Neuss diretto da Robock per addestrare il personale»: Robock che, per la procura, è uno scienziato al soldo dell’industria, mentre Di Amato ne rimarca «la serietà nello studio delle polveri e l’autorevolezza dei suoi lavori scientifici ancora oggi consultati e considerati punto di riferimento». All’attività di formazione del personale, si affiancò la creazione di organismi interni di controllo, come il Sil e il Copae. Anche qui due visioni diverse: per l’accusa i rilievi e i dati del Sil erano «inadeguati e inaffidabili», per la difesa, invece, erano fondati: «Certo – ha commentato Di Amato -, si potevano fare in modo diverso, ma con il sapere di vent’anni dopo!».

INVESTIMENTI E INTERVENTI

Lo ha detto chiaramente l’avvocato Di Amato: «Servono gli interventi tecnici, ma necessitano anche quelli economici».

Qui si inserisce il controverso capitolo degli investimenti e dei flussi di denaro arrivati dalla Svizzera verso la Eternit italiana: tanti, pochi, adeguati, insufficienti? La procura, principalmente sulla base della ricostruzione del consulente Paolo Rivella, che ha esaminato e studiato la documentazione reperita, ritiene che gli investimenti siano stati insufficienti a voler rispettare le norme dell’epoca, e, comunque, ha lamentato dati diversi, confusi e contrastanti forniti dalla difesa, tra un processo e l’altro, sui reali importi. Il difensore attribuisce la causa dell’imprecisione delle cifre al fatto «che la documentazione di questo procedimento penale sarà ampia, come dice il pubblico ministero, ma è monca, perché una grossa parte è andata distrutta nell’alluvione avvenuta a Genova (dove c’era la sede legale di Eternit, e poi l’amministrazione controllata, da metà degli anni Ottanta fino al fallimento del 1986, ndr)». Il difensore insiste comunque sulla cifra di 33 miliardi di lire spesi in interventi destinati alla sicurezza, dati contestati invece dalla procura (che evidenzia come credibile unicamente un foglio trovato nella famosa «stanzetta segreta» dello stabilimento casalese, sul quale erano annotati interventi per soli 4 miliardi di lire). Ma a questo punto, Di Amato contesta, a sua volta, l’operato di Rivella. A suo parere potrebbe addirittura aver taciuto dei dati perché l’esito della consulenza fosse funzionale alla tesi del pm.

In realtà, l’attacco è più esteso ai consulenti della procura. Il difensore prende spunto da una affermazione contenuta nella sentenza della Corte d’Assise di Novara secondo la quale i consulenti del pubblico ministero sarebbero più affidabili di quelli della difesa, in quanto questi ultimi vengono pagati per portare prove a favore dell’imputato. «Non è accettabile questa affermazione!» ha detto Di Amato.

Ha contestato sia Rivella sia Irma Dianzani. L’attacco a Rivella riguarda specialmente il capitolo degli investimenti; quello a Dianzani si riferisce a una risposta reputata imprecisa data dalla consulente a una domanda dei difensori; per inciso, la domanda di argomento epidemiologico è stata rivolta a una scienziata che è invece genetista.

Il difensore ha insistito comunque sul fatto che interventi ne sono stati fatti e, a sostegno della sua argomentazione, ha letto stralci di una relazione dell’Ispettorato del Lavoro, datata 1987, in cui è scritto che «all’inizio del 1974, anche a seguito di una variazione societaria (gli svizzeri acquisiscono quote dai belgi e assumono la maggioranza, ndr), l’azienda ha avviato un vasto piano di ammodernamento», per esempio trasformando il processo produttivo «da secco a umido». Ha letto anche un passaggio della relazione del commissario giudiziale Carlo Castelli, scritta nell’ambito della procedura di amministrazione controllata cui la Eternit era stata ammessa dal 1983: «Sono stati fatti investimenti al limite massimo tecnicamente ottenibile».

RESPONSABILITA’ DEL VERTICE E MANUTEZIONE CARENTE

«Allora era tutto perfetto?»: l’interrogativo, in forma retorica, lo solleva lo stesso Di Amato. No; un grosso impatto, nella diffusione delle polveri, viene attribuito dalla difesa alla manutenzione carente: «Se, ad esempio, un filtro intasato non veniva sostituito…». Di questo tipo di inadempienza, però, dice il legale, non può certo rispondere Schmidheiny che era al vertice «del grande gruppo svizzero di cui facevano parte mille società (una era la Swatch degli orologi); tra queste, c’era il gruppo del cemento amianto che contava 60 stabilimenti nel mondo, nel cui contesto, a sua volta, c’era il gruppo italiano con 5 stabilimenti. E poteva sapere se il filtro si intasava?».

Al vertice di un gruppo di queste dimensioni si deve chiedere conto, caso mai, delle scelte strategiche, degli investimenti, della gestione, delle metodologie produttive, degli interventi di prevenzione e sicurezza.

LA CITTA’ «IMBOTTITA» DI AMIANTO: POLVERINO E BATTUTI

Tra le indicazioni strategiche arrivate dall’alto, la difesa cita il divieto, imposto da Schmidheiny nel 1976 quando assunse la guida del settore amianto (per inciso, l’avvocato di parte civile Esther Gatti affermò che dell’ordine di questo divieto non si è trovata traccia), di distribuire all’esterno scarti di lavorazione (polverino e rottami), che in precedenza, ha rimarcato Di Amato, erano invece ceduti per coibentare i sottotetti, per fare i battuti di cortili, campi da gioco, strade. E questo che cosa ha determinato? «Che la città era “imbottita” di amianto» a causa dei cosiddetti «usi impropri».

Forse, essendo a conoscenza di questa pericolosa pratica diffusa, Stephan Schmidheiny avrebbe dovuto informare le autorità pubbliche del grave rischio che i cittadini correvano. Invece no.

Proprio sugli «usi impropri», il professor Andrea D’Anna, consulente della difesa, aveva fatto una relazione, partendo dall’esame dei dati dell’Arpa Piemonte dai quali emergeva la situazione riassunta dal legale dell’imputato: «815 mila metri quadrati di coperture usurate, 4635 metri quadri di pannelli (feltri) di amianto, 11mila metri quadri di superficie coperta da polverino nei sottotetti, 28 mila metri quadrati di battuto con la presenza di polverino. Dati che un altro consulente della difesa, Canzio Romano, ha incrociato anche con le residenze delle vittime». La Corte d’Assise di Novara, però, non ha tenuto in grande considerazione la consulenza del professor D’Anna, evidenziando che lo studio era stato condotto senza mai andare sul posto.

Effettivamente, ricordiamo la descrizione della città di Casale fatta dal professore, descrizione, diremo così, piuttosto sorprendente per i casalesi: una distesa di case basse circondate da campi? Una rappresentazione assai poco realistica della antica città, capitale storica del Monferrato!

Di Amato, invece, ha rimarcato il rilievo della consulenza D’Anna, per sottolineare la presenza massiccia di amianto a causa degli usi impropri nel territorio («concessi in epoca precedente a Schmidheiny»), fonte di pesante diffusione di fibre.

Gli impieghi impropri dell’amianto in città e nei paesi circostanti sono un fatto innegabile; le riserve, nei confronti del professor D’Anna, avevano però riguardato sia il fatto di aver osservato la città (ai fini di una consulenza così importante) soltanto tramite Google Maps, sia l’aver pressoché equiparato, se non addirittura indicato come prevalente l’inquinamento da usi impropri rispetto a quello determinato dallo stabilimento e dai luoghi di pertinenza dell’Eternit.

Tra gli altri, la famosa area ex Piemontese, tra le case del Ronzone, dove avveniva la frantumazione a cielo aperto degli scarti, pratica per la quale, come ha con precisione ricordato Di Amato, lo stesso Robock, dopo una visita a Casale tra il 27 e il 28 marzo 1980, aveva espresso contrarietà: «Non dovrebbe essere consentito frantumare i cascami in spazio aperto senza uso di acqua»: questo scrisse nel suo report.

La pratica, che si svolgeva 24 ore su 24, con una ruspa che passava avanti e indietro sui rottami, era iniziata proprio dopo il 1976, nell’epoca di gestione di Schmidheiny, quando era stato costruito il Mulino Hazemag, per utilizzare una parte degli scarti nel processo di lavorazione. A chi spettò e chi prese la decisione strategica di realizzare il Mulino Hazemag e di utilizzare i cascami fatti arrivare, tra l’altro, non solo da Casale, ma anche da altri stabilimenti?

E questa sorgente di inquinamento – frantumazione H24, senza protezioni – sarebbe stata davvero meno importante di un sottotetto con il polverino, come ebbe a ipotizzare il professor D’Anna?

MA PERCHE’ L’ETERNIT FALLISCE?

Il difensore ha, poi, dato voce a una domanda che la sua puntuale e chiara illustrazione dello svolgimento dei fatti e descrizione dei luoghi, fa sorgere spontanea: «Come ha fatto, allora, un’impresa gestita bene, con flussi di denaro continui e con supporti tecnologici adeguati all’epoca, continuare a perdere fino a fallire?».

La risposta è stata attinta dalla relazione del già citato dottor Castelli, che scrisse: «L’impresa Eternit ha fatto investimenti, ma i concorrenti più piccoli non hanno fatto altrettanto per risanare l’ambiente di lavoro. Il Governo italiano – ammonì Castelli – dovrebbe adottare al più presto la direttiva dell’Unione Europea affinché tutti i produttori siano tenuti a rispettare norme e limiti». Qui, ha spiegato Di Amato, sta la spiegazione dell’epilogo fallimentare: «L’Eternit si è caricata di costi maggiori e, quindi, è risultata meno competitiva sul mercato», fino a non poter più reggere.

Il fallimento è del giugno 1986, ma la società aveva già deciso il percorso di chiusura nel 1983 a Zurigo.

NASCONDIMENTO

In quell’anno, fu ingaggiato Guido Bellodi, accreditato professionista milanese della comunicazione. Gli venne affidato il compito «di gestire uno scandalo finanziario», appunto in vista del preordinato fallimento di Eternit. Lo ha spiegato, in modo esplicito, l’avvocato Di Amato: «Gli Schmidheiny sono una famiglia di spicco in Europa, con un elevato potere economico. Soprattutto in quell’epoca, a far fallire una propria società ci si perdeva la faccia». Ecco che cosa doveva fare Bellodi: gestire l’immagine collegata al fallimento di una società dell’importante gruppo Schmidheiny. Ma in questo, secondo la difesa, non c’è nessun tentativo di nascondimento. A tal proposito, il legale ha portato un esempio: la lettera che il sindaco dell’epoca Riccardo Coppo aveva scritto nel 1985; indirizzata a chi? «A Stephan Schmidheiny, a Niederurnen, e, per conoscenza, al prefetto e ai sindacati. Quindi, si sapeva chi era Schmidheiny, qual era il suo ruolo e non era affatto nascosto!».

Il richiamo a quella lettera, tra l’altro, evoca la precisa testimonianza di Coppo quando fu sentito nel maxiprocesso Eternit 1. Fu lui stesso a produrne copia, il cui originale è custodito nell’archivio del Comune di Casale. Perché l’aveva scritta? Spiegò così: «Avevamo ricevuto dalla società molte e reiterate promesse che si sarebbe costruito uno stabilimento nuovo più sicuro (il pm Colace ha parlato di “Chimera Casale 3”, ndr)». Ma dalle parole non si passava mai ai fatti. E intanto i malati e i morti crescevano. Da qui la lettera dai toni decisi che, come ha precisato il difensore, è del 1985. Intanto, a Zurigo, già due anni prima, era stata presa la decisione di far fallire l’azienda. Che valore avevano, allora, le reiterate promesse (quanto meno quelle tra il 1983 e il 1985) di costruire uno stabilimento nuovo che avrebbe consentito di superare i problemi ambientali della vecchia fabbrica realizzata nel 1906? Una risposta l’aveva data Coppo: «Avevamo capito che ci prendevano in giro». E, come ebbe a dire un altro teste di spicco, Bruno Pesce, «si è spremuto il limone finché si è potuto».

UNICO PROCESSO PENALE AL MONDO

«I problemi derivanti dall’amianto – ha evidenziato infine il difensore – non riguardano soltanto l’Italia, è una tragedia globale. Però – ha stigmatizzato Di Amato – l’Italia è l’unico Paese al mondo in cui si celebrano processi penali per l’amianto, anche oggi. C’è stato un tentativo in Francia, qualche anno fa, ma il fascicolo è stato archiviato».

Effettivamente, nelle altre parti del mondo, si procede direttamente con cause civili finalizzate alla richiesta di risarcimenti economici a favore di chi ha subito malattie (o decessi) di origine professionale e ambientale.

E’ stato citato proprio in questo processo d’appello il caso della Johns Manville americana che, negli anni Ottanta, era stata travolta e sommersa da 16.500 cause civili.

Recentissima, poi, è la sentenza in Francia nei confronti della società CMMP, emessa mercoledì 27 novembre: la Corte d’Appello di Parigi ha condannato la Comptoir de minéraux et matières premières, che ha macinato amianto dal 1938 al 1975 nello stabilimento nel centro di Aulnay-sous-Bois (Senna-Saint-Denis), a pagare al Comune quasi 14 milioni di euro. Secondo i giudici questo è il risarcimento dovuto per la bonifica del sito che, nel corso dei decenni, ha causato migliaia di vittime, tra cui i bambini che, per 37 anni, avevano frequentato le scuole nei dintorni.

In Italia, dove l’azione penale è obbligatoria, la procura si è impegnata, invece, a valutare e accertare se sia stata una specifica condotta personale a causare tutti quei morti.

La collettività casalese, esemplare e moralmente integra, ha subito un torto grave, è fuor di dubbio. C’è bisogno di capire se qualcuno, e chi, lo ha commesso.

Per la difesa, dal momento che «non c’è un signor Eternit», non è Stephan Schmidheiny il responsabile.

La procura è convinta del contrario.

Un giudizio di primo grado è già stato espresso. Non resta che attendere il verdetto della Corte d’Assise d’Appello, il prossimo anno.

TRANSLATION BY VICTORIA FRANZINETTI

“Mr. Stephan Schmidheiny, with great honesty your lawyer said that the Casale community is exemplary and morally upright, has suffered and is suffering. Mr. Schmidheiny, don’t you think, that the time has come to take on the direct and personal coordination and financing of serious as a philanthropic entrepreneur, funding effective research that will produce a treatment for all mesothelioma patients in the world?”

ETERNIT BIS HEARING 4.12.2024

THE DEFENCE

SUMMARY

* Tragedy with thousands of deaths

* Forcing will not lead to justice

* Awareness

* Investment and intervention

* Top management responsibility and poor maintenance

* The city ‘stuffed’ with asbestos: dust, screeds and floorings

* why did Eternit go bankrupt?

* concealment at the top level

* The only criminal trial in the world

POINT BY POINT

TRAGEDY WITH THOUSANDS DEAD

‘What has struck the town of Casale is a tragedy because of the thousands of deaths caused by a terrible disease. Terrible, yes, one dies of suffocation. This tragedy has struck an exemplary community. We have been meeting them for some twenty years (starting with the investigation of the Eternit 1 Maxi Trial) and we only ask for respect for our role. A community whose common denominator is moral integrity. When Mrs Romana was remembered in this courtroom, I felt proud to have known her’.

This is how lawyer Astolfo Di Amato began, defending the Swiss entrepreneur Stephan Schmidheiny with his colleague Guido Carlo Alleva […]. After the public prosecutors (Drs Sara Panelli, Gianfranco Colace, Mariagiovanna Compare) and the plaintiffs’ lawyers (among others, Lawyers Laura D’Amico, Maurizio Riverditi, Giacomo Mattalia, Esther Gatti, Laura Mara, Alberto Vella, Alessandro Mattioda), it was now the turn of the defence. They had already started on 27 November, with some preliminary remarks. At the hearing on Wednesday, 4 December, they moved on to examine the issues on merit. Lawyer Di Amato covered the first part; on Wednesday 11 December, lawyer Alleva will complete it.

A tragedy. There is no – and could not be – difference of opinion between the parties on this point: the terrible and painful trickle of mesothelioma deaths began many years ago and continues. And the subsequent consideration is also widely shared: ‘A tragedy that strikes a community of exemplary integrity needs justice,’ said Di Amato.

FORCING DOES NOT LEAD TO JUSTICE

In justice, one must be careful of forcing; in fact, what justice is it?’. The meaning of this question for the lawyer translates as follows: is wanting at all costs the conviction of the defendant Stephan Schmidheiny a true answer of justice? A rhetorical question that, for the defence, already encapsulates the answer: no. And why? The explanation is summarised in the final passage of lawyer Di Amato’s speech: ‘Schmidheiny is not a scoundrel. Schmidheiny is a ‘son’ of his time (40-50 years ago: he was head of Eternit between 1976 and 1986, ed.). Sticking to the knowledge and technical support of the time, he was confident that he could use asbestos in a controlled manner. Then, yes, he was proved wrong, because the deaths continued, but the knowledge of the time did not yet allow us to know that there is no minimum threshold that eliminates the risk of falling ill with mesothelioma. It was only known in the 1990s’. The defence lawyer insisted: ‘The defendant’s conduct did not violate the regulations’. All the more so, he remarked, that ‘the Casale area was literally “stuffed” with asbestos, but not through Schmidheiny’s fault; it had happened before his arrival in 1976’. Henceforth, the arguments diverge from those of the prosecution and the plaintiffs, and also from the first-degree verdict of the Novara Assize Court, which sentenced the defendant to 12 years’ imprisonment for manslaughter (and not intentional murder as per the PPs request ) of 147 victims, [while the statute of limitations applied to 199 cases and in he was acquitted for 46 cases.

AWARENESS

The defence does not deny that the defendant was aware of the risks of asbestos, but not to the extent that people became aware of them after 1986 and even more so in the 1990s. However, the minutes of the Neuss Conference show the defendant’s exact knowledge of how harmful asbestos was. And there are Schmidheiny’s quoted statements. ‘To be or not to be?’ was the Hamlet’s question he asked himself, meaning “should we continue to use it or stop altogether”, knowing that it causes mesothelioma? He chose ‘to be’, i.e. to continue. And, again, it is Schmidheiny who speaks: ‘We must obtain the best result with the least effort’. According to the Prosecution, this statement is indicative of a desire to exploit the business as much as possible while spending as little as possible on safety. For the defence, on the other hand, the defendant’s position at the time was this: ‘It is important that there is a change in everyone’s mentality. The guiding star of the business cannot only be productivity, but also respect for health and the environment’. This was Schmidheiny’s intention at the Neuss conference, and, above all, a few months later, when he issued the Auls manual to be scrupulously adhered to when giving information on asbestos (to workers, their families, trade unionists, journalists, public administrators). As the plaintiff lawyer Maurizio Riverditi said, ‘you cannot get inside the defendant’s head; to understand what he had in mind, you have to analyse the facts’. For the defender Di Amato, this analysis of the facts can be traced back to the intention of ‘respecting the rules, if someone complains let him talk to the workers and, if he is still not convinced, give the answers indicated in Auls’. Not least because, Di Amato observes, ‘to give correct information, it is not obligatory to shock!’. A word that had emerged precisely in the Neuss minutes, documenting what had been the reaction of the 35 top managers summoned by the Swiss entrepreneur when he had explained the harmfulness and deadly risks of asbestos: they had been ‘shocked’.

Disposing of asbestos was difficult in any case. The defendant pointed out that, in 1982, people were not yet ready to replace it, for example in the manufacture of pipes for pipelines, because there were no other materials that ‘could withstand the pressure’. In addition, Di Amato recalled Irving Selikoff, who at the International Conference in New York in 1964 had sounded the alarm about the danger of asbestos as a cause of mesothelioma not only for those who worked with itBut the lawyer pointed out, ‘in an interview given to the New York Times in 1976, the scientist stated that “the prohibition of asbestos is not necessary”’, i.e., the defence lawyer summarised, ‘it could be used in a controlled manner’. According to the defence, this was the actual awareness of the defendant between 1976 and 1986. And, indeed, since in the Italian plants the approach to technical and safety requirements was deficient compared to what was already taking place in the Swiss plants, Schmidheiny made the Neuss laboratory directed by Robock available to train the staff’. Robock, according to the prosecution, was a scientist for industry, while Di Amato emphasises “the seriousness of his study of dust and the authoritativeness of his scientific works, which are still consulted and considered a reference point”. Alongside the training of personnel, there was the creation of internal control bodies, aka Sil and Copae. Here too, two different visions: for the prosecution, Sil’s findings and data were ‘inadequate and unreliable’, for the defence, on the other hand, they were well-founded: ‘Of course,’ Di Amato commented, ‘they could have been done differently, but with the knowledge of twenty years later!

INVESTMENTS AND INTERVENTIONS

Lawyer Di Amato made it clear: ‘Technical interventions are needed, but economic ones are also needed’. This is where the controversial chapter of investments and money flows from Switzerland to Italian Eternit comes in: many, few, adequate, insufficient? The prosecution, mainly according to the reconstruction by consultant Paolo Rivella, who examined and studied the documentation found, believes that the investments were insufficient to comply with the regulations of the time; and, in any case, Rivella complained about different, confused and conflicting data provided by the defence, between one trial and another, on the real amounts. The defence attributes the cause of the imprecision of the figures to the fact ‘that the documentation in this criminal case may be extensive, as the public prosecutor says, but it is monolithic, because a large part was destroyed in the flood in Genoa (where Eternit’s registered office was located, and then the receivership, from the mid-1980s until the bankruptcy of 1986, ed.) However, the defence insists on the figure of 33 billion lire (about 16-17 million euros) spent on safety measures, a figure contested by the public prosecutor’s office (which highlights as credible only a sheet of paper found in the famous ‘secret room’ of the Casale plant, on which measures worth only 4 billion lire were noted). Lawyer Di Amato disputes Rivella. In his opinion, Rivella may even have withheld data so that the outcome of the consultancy would serve the prosecutor’s thesis.

The attack is more extended to the prosecutor’s consultants. The defence lawyer takes his cue from an assertion in the Novara Assize Court’s ruling that the prosecutor’s consultants are more reliable than those of the defence, because the latter are paid to bring evidence in favour of the defendant. ‘This statement is not acceptable!’ said Di Amato. He challenged both Dr Rivella and Prof Irma Dianzani. The attack on Rivella related especially to the investment chapter; that on Dianzani referred to an allegedly inaccurate answer given by the consultant to a question by the defence lawyers; incidentally, this question on the epidemiological subject was put to a scientist who is a gene expert. The defence insisted that interventions had been made and, in support of his argument, he read extracts from a report of the Labour Inspectorate, dated 1987, in which it is written that ‘at the beginning of 1974, following a change of ownership when the Swiss acquired shares from the Belgians and took over the majority, and the company launched a vast modernisation plan’, for example by transforming the production process ‘from dry to wet’. He also read a passage from the judicial commissioner Carlo Castelli’s report, written as part of the receivership procedure to which Eternit had been admitted since 1983: ‘Investments have been made to the maximum technically achievable limit’.

RESPONSIBILITY OF TOP MANAGEMENT AND DEFICIENT MAINTENANCE

‘Was everything perfect then?”: the question, in rhetorical form, is raised by Di Amato himself. No; a major impact, in the spread of dust, is attributed by the defence to poor maintenance: ‘If, for example, a clogged filter was not replaced…’. However, Schmidheiny, who was at the top ‘of the large Swiss group of which a thousand companies were part (one was the Swatch of watches), cannot be held responsible for this type of non-compliance,’ says the lawyer. And could you know if the filter was clogging?’. The top management of a group of this size should be asked to account, if at all, for strategic choices, investments, management, production methods, prevention and safety measures

THE CITY ‘STUFFED’ WITH ASBESTOS: DUST AND BEATINGS

Among the strategic indications coming from above, the defence cites the prohibition, imposed by Schmidheiny in 1976 when he took over the leadership of the asbestos sector (incidentally, the plaintiff’s lawyer Esther Gatti stated that no trace of this prohibition has been found), to distribute outside processing waste (powder and scrap), which previously, Di Amato remarked, was instead given to insulate the attics, to make the beatings of courtyards, playgrounds, roads. And what did this lead to? ‘That the city was ‘stuffed’ with asbestos’ due to so-called “misuse”. Perhaps, being aware of this dangerous widespread practice, Stephan Schmidheiny should have informed the public authorities of the serious risk citizens were running. On the ‘improper uses’, Professor Andrea D’Anna, the defence consultant, wrote a report, starting with the data from Arpa Piemonte suggesting: ‘815 thousand square metres of worn roofing, 4635 square metres of asbestos panels (felts), 11 thousand square metres of surface covered by dust in the attics, 28 thousand square metres of beaten surface with the presence of dust. Data that another defence consultant, Prof Canzio Romano, also cross-referenced with the victims‘ residences’. The Novara Court of Assizes, however, did not take Professor D’Anna’s advice into great consideration, pointing out that the study had been conducted without ever going to the site. Indeed, we remember the professor’s description of the town of Casale, a description, shall we say, rather surprising for the people of Casale: an expanse of low houses surrounded by fields? A very unrealistic representation of the ancient city, the historical capital of Monferrato! Lawyer Di Amato, on the other hand, emphasised the importance of D’Anna’s consultancy, to underline the massive presence of asbestos due to the improper uses in the area (‘granted in the era before Stephan Schmidheiny’), a source of heavy spread of fibres. The improper uses of asbestos in the city and surrounding towns are an undeniable fact; the reservations, however, against Professor D’Anna, concerned both the fact of having observed the city (for the purposes of such an important consultancy) only by means of Google Maps, and the fact of having almost equated, if not even indicated as prevalent, the pollution from improper uses with that caused by the plant and Eternit’s sites. The well-known former Piemontese area, between the Renzone houses, where the open-air shredding of waste took place, a practice for which, as Di Amato accurately recalled, Robock himself, after a visit to Casale between 27 and 28 March 1980, had expressed opposition: ‘Waste should not be shredded and crushed in open space without the use of water’ he wrote in his report. The crushing and grinding took place 24 hours a day, with a bulldozer passing back and forth over the scrap, had started right after 1976, during Schmidheiny’s era of management, when the Hazemag Mill had been built, to reuse some of the scrap. Who made the strategic decision to build the Hazemag Mill and to use the waste brought in, among other things, not only from Casale, but also from other factories? And would this source of pollution really have been less important than an attic with dust, as Professor D’Anna hypothesised?

BUT WHY DID ETERNIT GO BANKRUPT?

The defence lawyer then gave voice to a question that his precise and clear illustration of the unfolding of the facts and description of the places, made arise spontaneously: ‘How did a well-run company, with continuous flows of money and with technological support appropriate to the time, continue to lose until it went bankrupt?’. The answer comes from the report by the aforementioned Dr. Castelli, who wrote: ‘The Eternit company made investments, but smaller competitors did not do as much to clean up the working environment. The Italian government,’ Castelli warned, “should adopt the European Union directive as soon as possible so that all manufacturers are required to comply with standards and limits”. Here, Di Amato explained, lies the explanation for the bankruptcy epilogue: ‘Eternit was burdened with higher costs and, therefore, was less competitive on the market’, to the point where it could no longer hold its own. The bankruptcy was in June 1986, but the company had already decided on the path to closure in 1983 in Zurich.

HIDING

In that year, Schmidheiny hired Guido Bellodi, an accredited Milanese Public Relations consultant. He was given the task ‘to manage a financial scandal’, precisely in view of Eternit’s preordained bankruptcy. This was explicitly explained by lawyer Di Amato: ‘The Schmidheinys are a prominent family in Europe, with high economic power. Especially at that time, to make one’s own company go bankrupt was to lose face’. This is what Bellodi had to do: manage the image associated with the bankruptcy of a company of the important Schmidheiny group. But in this, according to the defence, there is no attempt at concealment. In this regard, the lawyer gave an example: the letter that the mayor of the time, Riccardo Coppo, had written in 1985; addressed to whom? ‘To Stephan Schmidheiny, in Niederurnen, and, for information, to the prefect and the trade unions. So, it was known who Schmidheiny was, what his role was, and it was by no means hidden!’. The reference to that letter, among other things, evokes Coppo’s precise testimony when he was heard in the Eternit 1 trial. It was he himself who produced a copy, the original of which is kept in the archives of the Municipality of Casale. Why had he written it? He explained: ‘We had received many and repeated promises from the company that a new, safer plant would be built ([pm?] Colace spoke of “Chimera Casale 3”, ed.). But words were never followed by deeds. And in the meantime, the number of sick and dead was growing. As the defence pointed out, the strongly worded letter dates from 1985. Meanwhile, in Zurich, already two years earlier, the decision had been taken to bankrupt the company. What was the value, then, of the repeated promises (at least those between 1983 and 1985) to build a new plant that would overcome the environmental problems of the old factory built in 1906? Former Mayor Coppo gave an answer: ‘We realised we were being taken for a ride’. And, as another prominent witness, Bruno Pesce, put it, ‘you squeezed the lemon as long as you could’.

THE ONLY CRIMINAL TRIAL IN THE WORLD

‘The problems caused by asbestos,’ the defendant finally pointed out, ‘do not only concern Italy, it is a global tragedy. However,’ Di Amato stigmatised, ’Italy is the only country in the world where criminal trials are held for asbestos, even today. There was an attempt in France, a few years ago, but the file was archived’. Indeed, in the other parts of the world, civil lawsuits are directly pursued to claim financial compensation for those who have suffered illnesses (or deaths) of occupational and environmental origin. This is the case of the American Johns-Manville, which had been overwhelmed by 16,500 civil lawsuits in the 1980s, cited in this very appeal process. Most recent, then, is the judgement in France against the CMMP company, issued on Wednesday 27 November: the Paris Court of Appeal condemned Comptoir de Minéraux et Matières Premières, which milled asbestos from 1938 to 1975 in its plant in the centre of Aulnay-sous-Bois (Seine-Saint-Denis), to pay the municipality almost €14 million. According to the judges, this is the compensation due for the clean-up of the site that, over the decades, caused thousands of victims, including children who had attended schools in the vicinity for 37 years.

In Italy, where criminal prosecution is compulsory, the prosecution must assess and ascertain whether it was specific personal conduct that caused all those deaths. The community of Casale, exemplary and morally intact, has been seriously wronged, there is no doubt. There is a need to find out whether someone, and who, committed it. For the defence, since ‘there is no Mr Eternit’, Stephan Schmidheiny is not responsible. The prosecution is convinced otherwise. A trial court verdict has already been delivered. All that remains is to wait for the verdict of the Court of Appeal next year. [what abt the Court of Cassation after that?]

Next hearing on December the 11th

Grazie!

Tanti troppi morti a cui va il nostro perenne ricordo fiumi di parole moltissimi soldi spesi tantissima ricerca ….. e avanti così ma dove è di casa la Giustizia?!? Auguriamoci arrivi quando no si sa . Ma Giusta Sia ! Grazie Silvana grande “ Portavoce” dei fatti !

Silva leggerti fa sembrare di essere lì … in aula … ad ascoltare, sono sicura che ho provato le stesse emozioni che hai provato tu che ascoltavi. Grazie per questa cronaca lucida e attenta, grazie per questo resoconto così prezioso.