SILVANA MOSSANO

Reportage udienza 8 ottobre 2021

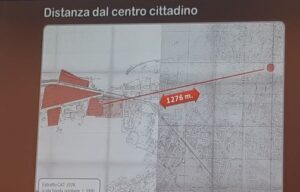

Prendendo come fulcro geografico di riferimento della città di Casale Monferrato il Duomo, la distanza dallo stabilimento Eternit, in via Oggero, quartiere Ronzone, è stata conteggiata in 1276 metri. Giusto per fare un paio di raffronti facili facili (agevolmente recuperabili in internet, ma di cui molti di noi hanno probabilmente esperienza diretta), è come percorrere solo per metà metà il Lungomare di Napoli (che misura poco più di 2500 metri) oppure fare una passeggiata di andata e ritorno dei Portici di via Po a Torino (700 metri).

A significare che la fabbrica dove si lavorava l’amianto come materia prima era a ridosso delle case. Tra le case, i negozi, le scuole.

Lo hanno dimostrato, con mappe, piantine e fotografie, i consulenti della procura Francesco Grassi e Laura Turconi che, nell’udienza di lunedì 8 ottobre 2021, sono stati esaminati al processo Eternit Bis, in cui l’imprenditore svizzero Stephan Schmidheiny, che di Eternit Italia è stato il proprietario e gestore diretto tra il 1976 e il 1986, deve rispondere dell’omicidio volontario (con dolo diretto) di 392 casalesi morti a causa dell’amianto.

L’AMIANTO DIFFUSO PER LA CITTA’

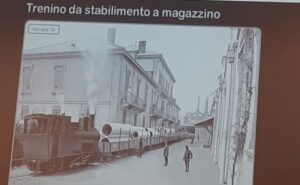

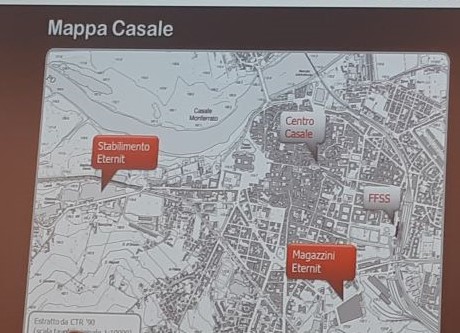

La raffigurazione grafica evidenzia una sorta di ragnatela di linee colorate, per lo più rosse e gialle, che disegnano i tragitti quotidiani, moltiplicati per decenni, del «trenino» e dei camion («non coperti» dicono i testimoni) che portavano i sacchi di materia prima dalla stazione ferroviaria allo stabilimento e i manufatti finiti (lastre e tubi) dalla fabbrica ai magazzini in piazza d’Armi collegati alla stazione; si aggiungono, poi, i percorsi dei camion che trasportavano rottami e scarti di lavorazione da via Oggero alla discarica Bagna, sulla sponda sinistra del Po.

Quando si dice che Casale Monferrato era la factory town dell’Eternit, cioè la città che si identificava con la sua fabbrica più importante (a fine 1976 occupava 1126 lavoratori, suddivisi in turnazioni diverse: da una a tre al giorno/notte), la definizione vale anche per il livello di permeazione del suo respiro nell’abitato: la polvere di amianto andava e veniva ovunque.

Era assai diffusa: più concentrata nel quartiere Ronzone, ma trasportata anche da e verso altri poli, funzionali all’attività industriale, raccontano i testimoni. Alcuni lo hanno anche già detto al processo in Corte d’Assise che si celebra a Novara. I difensori dell’imputato, Alfonso Di Amato e Guido Carlo Alleva, hanno però obiettato che, attorno all’Eternit, c’erano anche i cementifici: magari quelle «nuvole» che si sollevavano nell’aria o quegli strati in cui si piantavano i copertoni delle biciclette o che impregnavano le tute blu erano delle altre fabbriche della zona?

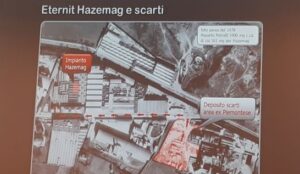

Per sciogliere i dubbi, i pm Gianfranco Colace e Mariagiovanna Compare hanno incaricato i loro consulenti di dare uno sguardo sul lato opposto dello stabilimento, quello affacciato sul fiume Po dove finivano gli scarichi di reflui contenenti materiale di risulta delle lavorazioni.

ACCUMULI SUL FIUME

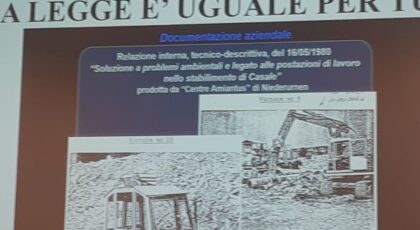

Gli esperti hanno esaminato documenti e riscontri tecnici, anche di provenienza aziendale, e hanno rilevato un «accumulo amiantifero sul fiume lungo 135 metri per oltre una quarantina, per una superficie di poco meno di 6500 metri quadrati, con uno spessore medio di 2 metri (ma in alcuni tratti anche di 4), pari a un volume di 12 mila metri cubi di deposito contenente amianto». C’erano sia il crisotilo (bianco) che la crocidolite (blu), come emerso dalle analisi allegate al piano di bonifica del 2006. «Gli scarichi liquidi di lavorazione e della pulitura delle macchine, attraverso una canaletta raggiungevano le acque del Po (…) formando incrostazioni: veri e propri strati “rocciosi” lungo l’argine ed entro il fiume».

«In sponda destra del Po, l’Eternit ha scaricato continuativamente materiali a elevato contenuto di amianto attraverso un canale proveniente dallo stabilimento». Nel 1980 fu progettato dall’azienda un impianto di depurazione che, dalle mappe, risulta essere presente dal 1981. Ma questo, ha ribadito nelle conclusioni la consulente Turconi, «non risulta aver ridotto significativamente i volumi di materiale ad alto contenuto di amianto dispersi in Po». E pure «in sponda sinistra risultavano scaricati rifiuti» anche in questo caso contenenti amianto: erano gli scarti che venivano convogliati nella discarica Bagna.

Per comporre un quadro numerico di riferimento la geologa ha riepilogato: «Venti tonnellate alla settimana di scarico “secco”, ossia 940 tonnellate all’anno, pari a circa 650 metri cubi all’anno, cioè 32 mila metri cubi di rifiuti contenenti amianto» scaricati nel fiume.

«E sono numeri in difetto» ha fatto presente Turconi, perché negli anni l’accumulo è stato eroso (e poi via via riformato) dalle piene annuali, tra cui quelle storiche più recenti del 1994 e il 2000. Ecco: nonostante le erosioni, gli accumuli raggiunsero quelle dimensioni.

«Entrambe le sponde del fiume Po – ha concluso la geologa – sono state oggetto di bonifica solo a partire dalla fine degli anni Novanta da parte delle amministrazioni pubbliche».

LA MAPPA DELLE VITTIME

Dove abitavano le 392 vittime – persone fatte per vivere, sicuramente per vivere ancora – dell’amianto elencate nel capo di imputazione del processo Eternit Bis?

La procura ha dato incarico a Dario Patricelli e a Fabio Belci di recuperare tutte le loro residenze (un lavoraccio che li ha portati a bussare agli uffici di 24 Comuni, principalmente Casale e dintorni), perché molti hanno vissuto in quartieri, frazioni o paesi diversi durante il corso della vita.

Per ciascuna delle 392 vite i consulenti hanno composto una scheda e hanno riportato uno spillo per ogni residenza sulla mappa del territorio casalese: in totale 933 residenze, riferite a 62 ex lavoratori e 330 cittadini che non avevano rapporti di lavoro con l’Eternit.

Un esempio di scheda? Quella di Paola Chiabrera: «Ha vissuto per sei anni nella frazione casalese di San Germano, ventun anni a Ozzano e dieci a Casale». Ciò che più colpisce, in questo caso, è l’anno di nascita: 1976, quello in cui Stephan Schmidheiny assunse direttamente il comando dell’Eternit in Italia. Non si potrà certo dire che Paola Chiabrera, morta di mesotelioma a 37 anni, ha respirato l’amianto delle gestioni precedenti.

Ci sono poi persone la cui residenza è fuori dal circondario di Casale. In questi casi, la ricerca dei consulenti è stata ancor più approfondita: hanno consultato anche i questionari, compilati dagli stessi malati, e raccolti dal «Renam» (Registro Mesoteliomi).

Ad esempio, Paola Biasi ha sempre vissuto a Genova, ma nei suoi primi sedici anni ha trascorso le vacanze in Monferrato, a Frassinello, uno dei paesi della cintura casalese.

Altro caso: Massimo Bonino, tra il 1976 e il 1986 (periodo di interesse per il processo che si celebra in Assise), era residente a Vercelli. E dunque? In quello stesso lasso di tempo, però, «faceva l’agente di commercio per una ditta di Casale».

PROSSIME UDIENZE

Venerdì 22 ottobre saranno esaminati i consulenti Stefano Silvestri e Alessia Angelini. Lunedì 25 ottobre, sarà interrotta momentaneamente la disamina degli esperti e saranno ascoltati alcuni testimoni: famigliari delle vittime che si sono costituiti parte civile.

Traduzione a cura di Vicky Franzinetti

SILVANA MOSSANO

October 8th 2021 Hearing

Taking the Cathedral as the point reference for the town of Casale Monferrato, there are 1276 metres to Eternit plant in Via Oggero, in the Ronzone district. A few easy comparisons (which can easily be found on the Internet, but which many of us have probably experienced personally): it is like walking halfway along the Naples seafront (just over 2500 metres) or taking a round trip of the Arcades in via Po in Turin (700 metres each way). This means that the plant where asbestos was processed as a raw material was close to the houses. Among the houses, shops, schools. At the at the Eternit Bis hearing on Monday 8 October 2021, the Prosecution’s expert witnesses Francesco Grassi and Laura Turconi, were heard and used maps, plans and photographs. [1]

HOW ASBESTOS SPREAD THROUGHOUT THE CITY

The graphs shows a sort of spider web of coloured lines, mostly red and yellow, drawing the daily routes, multiplied over decades, of the ‘little train’ and of uncovered lorries, say the witnesses, that carried sacks of raw material from the railway station to the plant and the finished products (sheets and pipes) from the factory to the warehouses in Piazza d’Armi and then to the station. The routes the lorries took transporting scrap and processing waste from Via Oggero to the Bagna dump on the left bank of the Po were also shown.

When people said that Casale Monferrato was Eternit’s factory town, i.e. the city identified with its most important factory, the definition also applies to the what air people breathed in the town: asbestos was present throughout, carried here and there. At the end of 1976 Eternit employed 1126 workers, on different shifts: from one to three per day/night. Eternit facilities were scattered: more concentrated in the Ronzone district, but also in other places, used for industrial activity, witnesses said. Some witnesses have already repeated it at the Assize Court trial in Novara. However, the defence lawyers, Alfonso Di Amato and Guido Carlo Alleva, objected that there were also cement factories around Eternit: perhaps they believe those “clouds” that rose twirling in the air or those layers in which bicycle tyres were planted or that impregnated blue overalls came from other factories in the area?

In order to clear up the doubts, prosecutors Gianfranco Colace and Mariagiovanna Compare asked their experts to look at the opposite side of the plant, the one facing the river Po, where the material from the process was discharged.

THE BUILD UP IN THE RIVER

Experts examined documents and technical evidence, some of it from the company, and found an “asbestos accumulation 135 metres long by over 40 along the river, covering an area of just under 6,500 square metres, with an average thickness of 2 metres (but in some places even 4), equal to a volume of 12,000 cubic metres of asbestos-containing deposit“. There was both chrysotile (white) and crocidolite (blue), as shown by the tests attached to the 2006 Town’s Reclamation Plan. “The liquid effluents from processing and cleaning the machines reached the waters of the Po through a channel (…) forming incrustations: real layers that were rock-like along the embankment and in the river”. “On the right bank of the Po, Eternit relentlessly discharged materials with a high asbestos content through a channel coming directly from the plant”. In 1980, the company designed a purification plant, which, according to maps, was opened in 1981. But this, as geologist Turconi reiterated in her conclusions, ‘it does not appear to have significantly reduced the volumes of material with a high asbestos content dispersed into the River Po’. And ‘waste containing asbestos was also dumped on the left bank’: it was the waste that was channelled to the Bagna. Let’s give a few figures for reference, the geologist summarised: “Twenty tonnes of ‘dry’ discharge per week, are 940 tonnes per year, about 650 cubic metres per year, that is 32 thousand cubic metres of waste containing asbestos” discharged into the river. “And these are conservative numbers,” Turconi pointed out, because over the years the accumulation has partly been washed away (and then gradually reformed) carried by annual floods, including the most recent major floods of 1994 and 2000. However, despite erosion, the behemoth build up is there to see . “No one but the local authorities have cleaned up both banks of the river Po, and that took place as from the 1990s” concluded the geologist ”

THE MAP OF THE VICTIMS

Where did the 392 asbestos live? They are the asbestos victims of Casale whose death is debated in the Eternit bis trial – people who could have lived, and certainly could have lived longer. The Prosecution instructed Dario Patricelli and Fabio Belci to map where they lived (a tough job that meant they had to knock on the doors of the offices of 24 districts, mainly Casale and its surroundings), because many had lived in different neighbourhoods, hamlets or villages during their lives. For each of the 392 lost lives, the experts prepared a card and placed a pin everywhere the people had lived: a total of 933 places, for the 62 former workers and 330 members of the community who never worked at the plant. An example of a card? Paola Chiabrera: ” For six years she lived in the Casale hamlet of San Germano, twenty-one years in Ozzano and ten in Casale“. What is most striking, in this case, is the year of her birth: 1976, the year in which Stephan Schmidheiny took direct control of Eternit in Italy. It cannot be said that Paola Chiabrera, who died of mesothelioma at the age of 37, breathed in asbestos under previous managements. Then there are people lived outside the Casale district. In these cases, research was even more thorough: they also consulted questionnaires filled in by the patients themselves and gathered by Renam (the Mesothelioma Registry). For example, Paola Biasi had always lived in Genoa, but in her first sixteen years she spent her holidays in Monferrato, in Frassinello, one of the villages in the Casale area. Another case: Massimo Bonino, between 1976 and 1986 (period of interest for the trial that is being held in the Assize Court), was resident in Vercelli. And so? In that same period of time, however, he was ‘working as a travelling salesman for a company in Casale’.

NEXT HEARINGS

On Friday, 22 October, consultants Stefano Silvestri and Alessia Angelini will be heard. On Monday 25 October, the series of expert witnesses will be momentarily interrupted and some witnesses will be heard: family members of the victims.

[1] The Swiss businessman Stephan Schmidheiny, who was the owner and manager of Eternit Italia between 1976 and 1986, stands accused of the murder (with wilfulness) of 392 people from Casale who died of asbestos related diseases.

Come sempre esposizioni chiare e dettagliate. Continua così.

Sempre Grazie per aggiornamento, gli scarichi che confluivano nel Po avranno inquinato anche i pesci da noi mangiati?!?!?!