SILVANA MOSSANO

Reportage udienza 13 settembre 2021

C’era polvere, polvere ovunque, ma proprio tanta polvere. Nicola Pondrano, la cui esistenza è stata scandita dalla lotta alla polvere d’amianto, l’ha vista tutta quella «pouvri», come la si chiama a Casale e dintorni, se l’è levata via d’addosso con il getto d’aria compressa, l’ha spazzata con la ramazza, l’ha respirata e l’ha portata a casa. «Quando penso a quel periodo, sto male, perché so che non mi sono tutelato a sufficienza e lo metto in conto quello che potrebbe succedermi, ma non mi perdonerei mai se dovesse capitare qualcosa a mia figlia». E che cosa mai potrebbe accadere a sua figlia? Pondrano, che all’Eternit, nel quartiere del Ronzone, ha lavorato dal 1974 al 1979, tornava a casa e la sua bambina gli saltava addosso. «Le ho consentito di giocare con i miei capelli»: si divertiva a tirar via quei «puntini bianchi» intrappolati nella capigliatura del padre.

IL PRIMO TESTIMONE

Nicola Pondrano è stato, lunedì 13 settembre, il primo testimone al processo Eternit Bis, davanti alla Corte d’Assise di Novara, chiamata a giudicare l’imprenditore svizzero Stephan Schmidheiny per l’omicidio volontario, con dolo eventuale, di 392 casalesi morti per il mesotelioma causato dall’amianto. Pondrano, dal 1979 in poi, benché fuori dalla fabbrica e in distacco sindacale, ha continuato a occuparsi di amianto: ha ricordato il suo ruolo di referente del patronato Inca della Cgil, le centinaia di cause che sono state intentate per conto dei lavoratori, il ruolo attivo, insieme a Bruno Pesce, nella nascita dell’associazione Afeva (Associazione famigliari e vittime amianto), nel 1988, «alla cui guida fu posta quella straordinaria donna che è Romana Blasotti Pavesi: le morì il marito, che era stato operaio all’Eternit, poi la sorella, il nipote e, il dolore più grande, la figlia Maria Rosa». Toccò a lei, Romana, indomita e carismatica presidente, e madre coraggio, leggere, in un’affollata assemblea pubblica del 27 agosto 2004, la lettera che sua figlia aveva scritto annunciando di essere, così come suo padre, sua zia, suo cugino, afflitta dal mesotelioma.

Il testimone Pondrano, ascoltato per oltre cinque ore, con una breve interruzione, è stato importante per ricostruire l’ambiente della fabbrica Eternit che, a Casale, ha operato per 80 anni, fino alla chiusura del 1986. La più grande d’Italia, e la più vecchia.

LE CONDIZIONI DI LAVORO

E in che condizioni si è lavorato?

Il teste ha riferito alla Corte, presieduta da Gianfranco Pezone (affiancato da Manuela Massino, più i giudici popolari), un episodio sintomatico: «Piero Marengo… aveva una cinquantina d’anni, ma ne dimostrava venti di più… seduto su un sacco contenente amianto, mangiava in pausa pranzo un panino di salame. Mi vede, ero giovane, circa 25 anni, e mi dice “Ma che cosa sei venuto a fare qua dentro? Sei venuto a morire anche tu?».

«L’AMIANTO NON E’ PERICOLOSO»

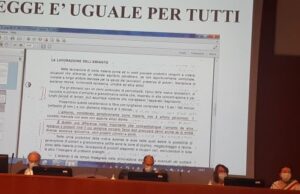

C’era la percezione che di polvere si moriva? «C’era, per molto tempo, la percezione che ci si ammalava di asbestosi polmonare; di mesotelioma, tra i lavoratori, si è cominciato a parlare dopo, verso la fine degli anni Settanta. Ma che cos’era ‘sto mesotelioma? Nel ’78 venimmo a sapere che alla nostra compagna di lavoro, la magazziniera Giannina Vitale, era stato diagnosticato il mesotelioma; morì che aveva una cinquantina d’anni». E l’azienda, incalza il pubblico ministero Gianfranco Colace, vi aveva dato delle informazioni sui rischi della malattia? Vi aveva indicato delle precauzioni precise? «In busta paga – ha spiegato Pondrano – una volta, direi nel ’77, è stato allegato un foglietto, forse di color giallognolo o verdognolo, in cui veniva minimizzata la pericolosità dell’amianto rispetto ad altre sostanze». Una copia di quel «foglietto» divulgato dalla dirigenza dell’Eternit è stata recuperata dagli inquirenti e si trova nel fascicolo processuale. Il pm lo proietta sullo schermo in aula d’Assise. Eccone uno stralcio che fa riflettere: «L’amianto, considerato semplicemente come materia, non è affatto pericoloso – sta scritto -; il contatto manuale con esso non apporta alcun danno. E’ questa una differenza molto importante che contraddistingue l’amianto da altre sostanze o prodotti finiti il cui semplice contatto fisico può procurare danni anche se di entità diversa: sostanze radioattive, certi prodotti chimici e simili».

Fa riflettere, sì, e fa rabbrividire la disinvolta sicurezza con cui furono divulgate queste affermazioni, perché – siamo nella seconda metà degli anni Settanta – i lavoratori dell’Eternit, no, ma i massimi vertici delle società amiantifere, sì, conoscevano i risultati degli studi scientifici mondiali che già da decenni associavano la fibra d’amianto al mesotelioma e al cancro ai polmoni. Sapevano, i vertici, che, anche solo un decennio prima di quel foglietto rassicurante, uno scienziato di nome Irving Selikoff aveva proclamato la cancerogenicità dell’amianto; e non si può dire che non sapessero chi fosse Selikoff, perché, contro di lui, avevano ingaggiato una agguerrita battaglia di denigrazione.

Rassicurazioni, dunque, dalla dirigenza: l’amianto non è pericoloso. Ma di manifesti funebri attaccati al muro dello stabilimento Eternit non ce n’erano un po’ troppi (con stampati sopra i nomi di lavoratori «ancora giovani – ha riferito Pondrano – tra i 50 e i 55 anni, prima dell’età per andare in pensione»)? In risposta a questo interrogativo legittimo va richiamato ancora il «foglietto» che offriva una chiosa finale: l’ammonimento, cioè, che è il fumo a essere dannoso, è quello a ingenerare il cancro.

IL DIRIGENTE RASSICURA

L’opera di tranquillizzazione, lo ha ricordato il testimone, non fu affidata soltanto a quel «foglietto» in busta paga. Ad esempio, ha evocato Pondrano, «il dottor Emilio Costa (dirigente Eternit e presidente della «Asbestos Association» di Londra cui aderivano oltre 340 industrie in una quarantina di Paesi, ndr), invitato al Rotary Club di Casale come relatore, dichiarò che l’amianto (più precisamente l’amianto blu) non faceva male. Uscì, nel merito, un articolo sul giornale locale e io – ha aggiunto il sindacalista – scrissi subito una lettera, a nome del consiglio di fabbrica, per smentire quelle affermazioni; non fu mai pubblicata».

TUTTA QUELLA POLVERE

Nelle cinque ore di testimonianza di Pondrano si è parlato così tanto di polvere che sembrava di vederla. Il teste ha detto come veniva percepita nello stabilimento: «Era una fabbrica vecchia di settant’anni, c’era tanta polvere, tanta umidità, tanto calore. Il primo giorno che ho fatto al “reparto lastre” non so quante bottigliette d’acqua ho bevuto, non riuscivo quasi a respirare». E, poi, c’era «la polvere della tornitura dei tubi, quella che oggi viene definita polverino, la più pericolosa: era ingovernabile. La si raccoglieva con la pala e la si buttava nei sacchi, non so che fine facessero quei sacchi pieni di polverino». Nella coibentazione dei sottotetti? Nel livellamento dei campetti di calcio e dei cortili? Lo ha ribadito Albino Defilippi, responsabile del Centro regionale Amianto Arpa Piemonte: «Il vero pericolo è il polverino».

LE BELLE TUTE BLU

E c’era la polvere sulle tute: «Le tute hanno avuto gravi responsabilità su quanto è successo a Casale, su tante morti. Le tute blu, allora, le si portava con fierezza, perché si era orgogliosi di lavorare all’Eternit. La tuta te la portavi a casa, impolverata, e le donne la lavavano». Povere donne che hanno inalato anche loro la «pouvri». «Ma prima di uscire dallo stabilimento, proprio per togliere la più “grossa”, si usava il tubo di aria compressa per spazzarla via, la polvere». Via dalla tuta, più che si poteva, ma quella che si sollevava andava su nel naso e nella gola, fino ai polmoni.

COL PRETE OPERAIO

Come si reagì? «Incontrai in fabbrica padre Bernardino Zanella, prete operaio, con lui ho fatto squadra; ma non era facile discutere di salubrità ambientale e di condizioni di lavoro dentro l’Eternit. Si sapeva delle malattie professionali, ma, per contraltare, c’erano i salari maggiorati anche del 30 percento rispetto ad altre aziende, l’indennità per la polvere, la lattina di olio d’oliva, la bocciofila, la sala da ballo, la colonia al mare, la medaglia d’oro dopo 25 anni di servizio e, magari, la speranza di “sistemare” i figli dopo il pensionamento dei genitori». Si provò a scalfire «quell’abbraccio mortale omertoso» utilizzando la bacheca aziendale «per comunicare ai lavoratori – in quegli anni sui 1200 – le rivendicazioni fatte e le risposte ricevute. Poi, anziché assemblee affollate, in cui nessuno parlava, ne organizzammo per gruppi omogenei e lì, con meno persone, qualcuno raccontava delle condizioni lavorative, dei problemi, “sto male, non dormo, sputo sangue”». Via via ne venne fuori una sorta di dossier: «Io – ha ricordato Pondrano – scrivevo a mano in stampatello, padre Bernardino a macchina: facemmo una mappatura delle criticità reparto per reparto».

Furono segnalate alla dirigenza. E si ottenne qualcosa? «Qualche miglioria tecnologica fu apportata, ma il problema della polvere non fu mai risolto davvero. Ci confrontavamo con il Sil (Servizio igiene e lavoro) diretto da Ezio Bontempelli, ma ci fidavamo poco dei loro risultati, perché era un organismo dell’azienda».

«Noi – ha proseguito il testimone – chiedevamo rilievi nei momenti particolari, in presenza di un guasto, della pulizia dei manicotti, del taglio manuale delle lastre o dell’apertura dei sacchi d’amianto col coltello». E i guasti capitavano «quasi quotidianamente. Un giorno, si era intasato il sistema di captazione delle polveri; Mauro Patrucco infilò il fischietto in bocca e proclamò sciopero seduta stante, ci fu un battibecco col caporeparto. Beh, Patrucco fu licenziato».

IL CONSULENTE SULLA SCALETTA

L’azienda, più avanti, convinse l’Inail che di polverosità all’Eternit non ce n’era più, tanto che era superfluo pagare il “sovrappremio” assicurativo per gli infortuni. Pondrano, all’epoca (inizio anni Ottanta), era già in distacco sindacale. «Lo scoprimmo per caso, presentammo denunce al pretore del lavoro di Casale che ordinò una perizia». Il consulente del giudice, professor Michele Salvini, dell’Università di Pavia, trovò lo stabilimento in ordine, spazzato, ma non ne fu né sorpreso né impressionato. «Si fece portare una scaletta, vi salì e, con un pennellino, fece scivolare in sacchetti di plastica la polvere che stava in alto, posata sulle sporgenze dei quadri elettrici. La esaminò: di amianto ce n’era eccome». Le cause promosse dai lavoratori, cui inizialmente era stata negata la «rendita di passaggio», furono vinte tutte.

MASCHERINE INADATTE

Il pm Colace ha insistito sulle protezioni: «E le mascherine? C’erano le mascherine?». Pondrano: «Sì, di stoffa, da morire soffocati. Non erano idonee per quel tipo di lavoro, non si potevano sopportare e, alla fine, la maggior parte dei lavoratori non le indossò più».

FRANTUMAZIONE A CIELO APERTO

Ma fuori, fuori dallo stabilimento? «C’era un’area, un po’ spostata rispetto all’ingresso principale e sul lato opposto, e dove adesso c’è l’asilo “Verdeblu”: lì, a cielo aperto e senza protezioni, venivano frantumati, passandoci sopra con una pala meccanica, gli scarti di lavorazione sia della fabbrica di Casale sia quelli arrivati dagli stabilimenti di Napoli, di Reggio Emilia, di Cavagnolo – ha spiegato il teste -. Tutti i prodotti di scarto arrivavano in quella zona e venivano sminuzzati a cielo aperto da un operaio. Un altro li caricava sul motocarro Aermacchi e, senza teloni di copertura, li portava nella fabbrica, a 400 metri di distanza, e li convogliava nel Mulino Hazemag: una parte veniva impiegata nell’impasto per la produzione dei manufatti, lastre o tubi».

Quest’area esterna, dove avveniva la frantumazione, era distante dalle case?, si è informato il pubblico ministero. «Le case sono lì, vicine, di lato, di fronte». La gente non si lamentava? «L’ottanta percento di quelle case erano abitate da lavoratori dell’Eternit e dalle loro famiglie».

Sul maxischermo dell’aula – l’aula magna dell’Università, adattata ad aula di Corte d’Assise – scorrono i filmati: quello dell’Archivio storico dell’istituto Luce, il documentario «Indistruttibile» di Michele Citoni, che raccontano per immagini i luoghi e le condizioni di lavoro.

I legali di parte civile – Laura D’Amico, Esther Gatti, Giacomo Mattalia, Laura Mara – incalzano: chiedono conto su tute, armadietti, sacchi contenenti l’amianto, sistemi di aspirazione.

Tutto – parole e fotografie, documenti e testimonianze – conferma che la polvere c’era.

IL NOCCIOLO PROCESSUALE

Questa è la cornice, poderosa sì, in cui si dovrà collocare la vera sostanza del processo. La cornice, però, non basta.

Non basta accertare che c’era molta polvere, e che in quella polvere era contenuta, sicuramente, la fibra di amianto, soprattutto la pericolosa crocidolite (impiegata per fare i tubi), e che la fibra d’amianto causa il mesotelioma.

Non basta: in questo processo difficile e dolorosissimo (perché scorrono le vite di 392 persone e altre centinaia di chi le ha amate) bisogna stabilire se la fibra, che si è insinuata subdola e silente nei polmoni, scatenando, a distanza di decenni, quei 392 mesoteliomi, sia riconducibile al periodo tra il 1976 e il 1986 in cui l’imputato Stephan Schmidheiny era a capo dell’Eternit.

Il nocciolo processuale sta qui e i difensori Astolfo Di Amato e Guido Carlo Alleva, anche attraverso domande apparentemente semplici, ma estremamente puntuali, poste al teste Pondrano (e che saranno rivolte a testimoni e consulenti che verranno), hanno dimostrato che è quello l’obbiettivo inderogabile. Pretenderanno di esaminare, legittimamente e minuziosamente, caso per caso. Chi mangiava in mensa, chi usava la ramazza, chi ha lavorato nella fabbrica quando c’era la lavorazione a secco (più pericolosa) e chi a umido (introdotta nel periodo Schmidheiny), chi abitava in città, chi viveva fuori, chi aveva a che fare con la fabbrica o chi no, chi ha lavorato all’Eternit e chi anche in altre aziende dove, pure, l’amianto era in qualche modo impiegato, chi è morto per mesotelioma e chi per un tumore diverso.

Se, fuori dal tribunale, il verdetto clinico, straziante e irreversibile, è inciso, lapidario, in una diagnosi inappellabile, in Corte d’Assise non basta: quei nomi, che è angosciante solo sentir pronunciare, con le loro sciagurate cartelle cliniche dovran dimostrare il preciso nesso causale tra la malattia e l’amianto. Quell’amianto, diffuso tra il 1976 e il 1986.

Alla prossima udienza, venerdì 17 settembre, sono in programma le testimonianze di Bruno Pesce, portavoce Comitato Vertenza Amianto, Giuliana Busto, presidente Afeva, e Alberto Cirio, attuale presidente della Regione Piemonte.

* * *

Traduzione del testo a cura di Vicky Franzinetti

SILVANA MOSSANO

There was dust, dust everywhere, a lot of dust. Nicola Pondrano, whose life has been lived in the fight against asbestos dust, saw all that “pouvri“, as it is called in Casale and the surrounding area, brushed it off his overalls with a compressed air jet, swept it up with a broom, breathed it in and took it home. “When I think about that time, I feel bad, because I know that I didn’t protect myself enough. I know what could happen to me, but I would never forgive myself if something were to happen to my daughter”. And what could happen to his daughter? Pondrano, who worked at Eternit in the Ronzone district from 1974 to 1979, would come home and his little girl would jump on his lap. “I let her play with my hair”: he enjoyed pulling out those “white spots” trapped in his father’s hair.

THE FIRST WITNESS

On Monday 13 September, Nicola Pondrano was the first witness of the Eternit Bis trial, in the Novara Court of Assizes, wilful intention (aka voluntary manslaughter or wilful murder in other legal systems) of 392 people from Casale who died of mesothelioma caused by asbestos. From 1979 onwards although outside the factory and a full time union official, Pondrano has continued to fight asbestos: in his testimony he referred to his role as contact person for the CGIL’s Union Assistance and Welfare Office], in the hundreds of cases that have been brought to court on behalf of workers. In 1988 he played an active role in setting up the Afeva association (Associazione famigliari e vittime amianto – Association of Asbestos Victims and Families) with Bruno Pesce, “headed by an extraordinary woman Romana Blasotti Pavesi: Her husband, who had been a worker at Eternit, died, then her sister, nephew and, the greatest sorrow, her daughter Maria Rosa”. on 27 August 2004 Romana, the indomitable and charismatic president and mother courage, read the letter her daughter had written announcing to a crowded public assembly that like her father, aunt and cousin, she too had developed mesothelioma.

Pondrano was heard for over five hours, with one brief interruption, and described the working environment of the Eternit factory that was in Casale for 80 years, until it closed in 1986. The largest in Italy, and the oldest.

WORKING CONDITIONS

What were the working conditions?

The witness told the court, presided by Chief Justice Gianfranco Pezone (with Justice Manuela Massino, and the Jury (aka popular judges), a symptomatic episode: “Piero Marengo … was about fifty years old, but looked over seventy… sitting on a bag containing asbestos, eating a salami sandwich during his lunch break. He saw me, I was young, about 25 years old, and he said to me: “What did you come here for? Have you come to die too?”

“ASBESTOS IS NOT DANGEROUS”.

Did people perceive the dust related deaths? “For a long time, we thought people fell ill with pulmonary asbestosis; workers started speaking about mesotheliomas at a later stage, towards the end of the 1970s. We were asking ourselves what was mesothelioma? In 1978 we learned that our workmate, the warehouse worker Giannina Vitale, had been diagnosed with mesothelioma; she died when she was about fifty years old. And did the Company, urged Public Prosecutor (PP) Gianfranco Colace, inform you of the risks of the disease? Did they list precise precautionary measures? “In the payroll,’ Pondrano explained, ‘once, I would say in 1977, they enclosed a leaflet, yellowish or greenish in colour, which minimised the danger of asbestos compared to other substances. A copy of that “leaflet” disclosed by the Eternit management was recovered by the investigators and is in the trial file. The prosecutor projected it on the screen in the Assize Court. Here is a thought-provoking excerpt: “As a material, asbestos is not dangerous at all – it is written -; handling it does not cause damage. This is a very important difference that distinguishes asbestos from other substances or finished products whose simple physical contact can cause damage, even if of different order of magnitude: radioactive substances, certain chemical products and the like’.

It gives one food for thought, and makes one shudder: the sort of off-handish self confidence with which these statements were circulated, because – and by now it was the second half of the 1970s – the Eternit workers did not know, but the top management of the asbestos companies did, and they knew the results of worldwide scientific studies that for decades had already associated asbestos fibres with mesothelioma and lung cancer. Companies were aware that a decade before that reassuring leaflet, a scientist called Irving Selikoff had revealed the carcinogenicity of asbestos; and it cannot be said that they did not know who Selikoff was, because they had waged a fierce battle to smear him.

Reassurance, then, from the management: asbestos is not dangerous. However, lot of death notices were stuck on the wall of the Eternit plant (with the names of workers printed on them who were “still young,” Pondrano reported, “between 50 and 55, before the age of retirement”)? In response to this legitimate question, the ‘leaflet’ should have been recalled, which led to a concluding remark: the warning, that is, that it is smoking that is harmful, it is smoking that causes cancer.

THE MANAGER REASSURES

The witness recalled that the reassurance was not only due to the ‘note’ in the pay packet. For example, recalled Pondrano, ‘Dr Emilio Costa (Eternit manager and president of the “Asbestos Association” in London, which more than 340 industries in forty or so countries belonged to), invited to the Rotary Club of Casale as a speaker stated that asbestos (more precisely blue asbestos) was not harmful. An article on the subject appeared in the local newspaper and I immediately wrote a letter, on behalf of the workers’ council, to refute those statements but it was never published.

ALL THAT DUST

In Pondrano’s five hours of testimony, there was so much talk of dust that it seemed as if one could see it. The witness said how it was felt in the factory: ‘It was a seventy-year-old factory, there was a lot of dust, a lot of humidity, a lot of heat. The first day I went to the “sheet workshop” I don’t know how many bottles of water I drank, I could hardly breathe”. And then there was ‘the dust from turning the pipes, what is now called powder, the most dangerous dust: it was unmanageable. We used to pick it up with a shovel and throw it in sacks, and I don’t know what happened to those sacks full of dust”. In the insulation of attics? In the levelling of football pitches and courtyards? Albino Defilippi, head of Arpa Piemonte’s Regional Asbestos Centre, reiterated: “The real danger is the dust”.

THE BEAUTIFUL BLUE OVERALLS

And there was dust on the overalls: “The overalls were responsible for what happened in Casale, for so many deaths. Back then, you wore your blue company overalls with pride, because you were proud to work at Eternit. You took the overalls home, dusty, and the women washed them. Poor women who also inhaled the ‘pouvri‘. “Before leaving the factory, just to remove the “coarsest”, they used the compressed air blow the dust away”. The dust was blown off overalls as much as possible, but the dust rose up went up into the nose and throat and into the lungs.

WITH THE WORKER PRIEST

How did you react? “I met Father Bernardino Zanella, a worker priest, at the factory, and I teamed up with him; but it wasn’t easy to discuss environmental health and working conditions at Eternit. We knew about the occupational diseases, but on the other hand, there were wages that were up to 30 per cent higher than in other companies, the allowance for dust, the tin of olive oil given as a gift, the bowling alley, the dance hall, the seaside holiday camp, the gold medal after 25 years of service and, perhaps, the hope of your children having your place after you had retired. An attempt was made to break “that deadly embrace of silence” by using the company notice board “to inform the workers – in those years around 1,200 – of the claims made and the answers received. Then, instead of crowded assemblies, where no one spoke, we organised them in small groups of people working in similar places (aka homogenous groups) and there, with fewer people, someone would talk about working conditions, problems, “I’m sick, I don’t sleep, I spit blood”. A sort of dossier gradually emerged. Pondrano recalls “I used to write by hand in block letters, Father Bernardino by typewriter.”

They were reported to the management. And did they achieve anything? “A few technological improvements were introduced, but the dust problem was never really solved. We used to talk to the SIL (Servizio igiene e lavoro – Hygiene and Labour Service), directed by Ezio Bontempelli, but we had little faith in their results, because it was a company body.

“We would ask for measurements at particular times, when there was a fault, when the pipe couplings were being cleaned, when the sheets were being cut by hand or when the asbestos bags were being opened with a knife,” continued the witness. And faults happened “almost daily. One day, the dust collection system was clogged; Mario Patrucco stuck his whistle in his mouth and called a strike on the spot, there was a fight with the foreman. Patrucco was fired”.

THE CONSULTANT ON THE LADDER

The company later convinced INAIL (the National Workers’ Compensation Body) that there was no more dust at Eternit, so there was no need to pay the insurance “premium” for accidents. Pondrano, at the time (early 1980s), was already a full time union official. “We discovered it by chance, we filed a complaint with the labour court of Casale, which ordered an expert’s report. The judge’s consultant, Professor Michele Salvini from the University of Pavia, found the plant to be in order, swept, but was neither surprised nor impressed. “He had a ladder brought to him, climbed up and, using a small brush, slipped into plastic bags the dust that was lying on top, on the ledges of the electrical panels. He examined it: there was plenty of asbestos”. The cases brought by the workers, who had initially been denied a compensation, were all won.

INADEQUATE MASKS

Prosecutor Colace focused] on the protection: “What about masks? Were there masks?”. Pondrano: ‘Yes, made of cloth suffocating. They weren’t suitable for that kind of work, they were unbearable and, in the end, most of the workers didn’t wear them anymore’.

CRUSHING IN THE OPEN AIR

But outside the plant? “There was an area, slightly removed from the main entrance and on the opposite side, and where there is now the “Verdeblu” kindergarten: there, in the open and without protection, the processing waste was crushed, by passing over with a shovel, that is the factory in Casale and those who came from the plants of Naples, Reggio Emilia, Cavagnolo. All waste products arrived there and were shredded and crushed in the open air by hand. They were loaded on the Aermacchi motor truck and, without tarpaulins, to be taken] to the factory, 400 metres away, and to the Hazemag mill: part of it] was used in the mixture for the production of manufactured products, sheets or pipes”.

Was this outside area, where the crushing took place, far from the houses?”, the prosecutor inquired. “‘The houses are there, close by, on the side, in front’. Didn’t people complain? ” Eternit workers and their families lived in eighty per cent of those houses.”

On the big screen in the Courtroom – the main hall of the University, adapted for use as an Assize Court room – films were shown: the one from the Luce Institute’s historical archive, the documentary “Indestructible” by Michele Citoni, telling the story of the places and working conditions in pictures.

The plaintiffs’ lawyers – Laura D’Amico, Esther Gatti, Giacomo Mattalia, Laura Mara – pressed for an account of overalls, lockers, bags containing asbestos, and extraction systems.

Everything – words and photographs, documents and testimonies – confirms that the dust was there.

THE CASE

This is the powerful framework for the trial.

However, a frame is not enough. It is not enough to prove that there was a lot of dust, and that this dust certainly contained asbestos fibre, especially the dangerous crocidolite (used to make pipes), and that asbestos fibre causes mesothelioma.

In this difficult and extremely painful trial (because the lives of 392 people are awaiting the judgement, along with the hundreds of others who loved them), the Court has to establish whether the fibre, which insinuated itself subtly and silently into the lungs, triggering those 392 mesotheliomas decades later, can be traced back to the period between 1976 and 1986 when the defendant Stephan Schmidheiny was head of Eternit.

The core of the trial lies here and the defenders Astolfo Di Amato and Guido Carlo Alleva, also through apparently simple but extremely precise questions put to the witness Pondrano (and which will be addressed to other fact and expert witnesses), have shown that this is the main aim. They will demand to examine, legitimately and minutely, case by case. Who ate in the canteen, who swept the floors, who worked in the factory when there was dry processing (more dangerous) and who wet processing (introduced in the Schmidheiny period 1976-1986), who lived in the city, who lived outside, who had to do with the factory or who did not, who worked at Eternit and who also worked in other companies where asbestos was also used in some way, who died of mesothelioma and who died of a different tumour.

Outside the court, the heartbreaking and irreversible medical verdict is engraved in stone, with an unappealable diagnosis, in the Assize Court it is not enough: those names, distressing as it maybe to hear pronounced, with their wretched medical records, will have to prove the precise causal link between the disease and asbestos. That asbestos, spread between 1976 and 1986.

At the next hearing on 17 September, Ms Giuliana Busto and Mr Bruno Pesce from the Afeva association will be heard, as well as the current President of the Region Piedmont.

Preciso come sempre i

Dal Brasile seguimmo il processo ETERNIT BIS con molto interesse e speranza per la vittoria in memoria delle vittime deceduti e i suoi famigliari. Speriamo chi questa volta si faccia giustizia. In bocca al lupo!

A leggerti mi viene l’angoscia. Mi sento la gola secca come se avessi la polvere fra i denti. Mio padre che ha lavorato in quella fabbrica che preferisco non pronunciare è morto nel 1968. Allora la parola “mesotelioma” non si conosceva lo abbiamo scoperto negli anni novanta. Magra consolazione il riconoscimento successivo.

Grazie mille instancabile Silvana per i tuoi PUNTUALI e APPROFONDITI “reportage” anche su questo nuovo processo, in effetti il terzo, come sai bene : speriamo d’avvero che stavolta la giustizia si riesca finalmente ad affermarla!

Grazie per puntuale e preciso aggiornamento. Continua nella cronaca. E sempre Grazie Silvana !!Alla prossima. Buona giornata ciao