Venerdì 3 marzo «la» Romana compie 94 anni – Eternit Bis: «La storia di Casale: unicum che non si deve ripetere. Fu omicidio doloso» – Il Comune chiede una provvisionale di 50 milioni –

SILVANA MOSSANO

Reportage udienza di lunedì 27 febbraio 2023

Il caso di Casale Monferrato è un unicum, la sofferenza di questa collettività, l’agonia di chi riceve la diagnosi di mesotelioma e l’angoscia sospesa di chi teme che un colpetto di tosse o un sospetto mal di schiena possano tramutarsi in «quella» diagnosi costituiscono un unicum a livello planetario.

Non c’è un altro caso paragonabile a quello vissuto (e che ancora sta vivendo) dalla comunità casalese.

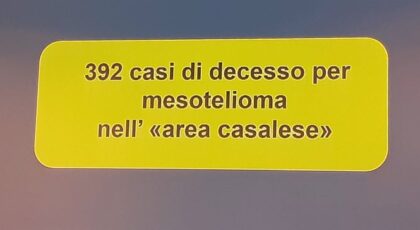

Il concetto è stato ribadito dai legali di parte civile nell’udienza di lunedì 27 febbraio al processo Eternit Bis che si svolge in Corte d’Assise a Novara. Un «unicum», senza altri paragoni al mondo, illustrato da angolazioni diverse per giungere a una conclusione condivisa: «L’imputato Stephan Schmidheiny è responsabile dell’omicidio volontario (se pur sorretto dall’eventualità del dolo) dei 392 casalesi, elencati nel capo di imputazione, morti a causa del mesotelioma». Gli avvocati che tutelano le parti civili (famigliari delle vittime, associazioni, enti e sindacati) ritengono di aver dimostrato, con argomentazioni articolate, che quei mesoteliomi sono stati provocati dalla diffusione consapevolmente dissennata dell’amianto, impiegato come materia prima nel ciclo produttivo dell’Eternit. L’Eternit di cui Stephan Schmidheiny è stato l’ultimo patron e gestore.

LE ARGOMENTAZIONI DELLE PARTI CIVILI

Le tesi, che si allineano alle conclusioni dei pubblici ministeri Gianfranco Colace e Mariagiovanna Compare (per i quali l’imputato è meritevole di condanna all’ergastolo senza il beneficio di attenuanti e con l’aggravamento dell’isolamento diurno), sono state suddivise e illustrate in diversi capitoli.

- Inquinamento dentro lo stabilimento

- Inquinamento all’esterno dello stabilimento

- La certezza delle 392 diagnosi di mesotelioma

- Il nesso causale tra amianto e mesotelioma, la validità della teoria multistadio e dell’anticipazione della malattia, oltre che gerarchia di autorevolezza delle tesi scientifiche

- Il dolo

- Il riconoscimento del danno ai singoli, agli enti, alle associazioni e ai sindacati, oltre che i criteri di quantificazione

INQUINAMENTO NELLO STABILIMENTO

«La Corte d’Assise è chiamata a giudicare una vicenda tragica che non solo ha superato i confini di Casale, ma anche quelli nazionali e internazionali». L’avvocato Laura D’Amico disegna un perimetro in cui collocare con ordine i fatti drammatici che si accinge ad affrontare.

Davanti a lei ci sono i giudici togati – il presidente Gianfranco Pezone e la giudice a latere Manuela Massino – e anche i giudici popolari che non hanno competenze giuridiche. Tutti insieme dovranno capire e valutare, per emettere un verdetto che tenga conto della condotta dell’imputato e della morte di 392 persone. Uccise, secondo il capo d’accusa.

E’ necessario procedere a una ricostruzione chiara e precisa.

«E allora andiamo a iniziare».

D’Amico comincia con la presentazione di Stephan Schmidheiny: «E’ un laureato in giurisprudenza, quindi parte da una formazione giuridica. Nel 1976 riceve formalmente l’incarico di gestire, nel mondo, le aziende di famiglia che si occupano di amianto. Al fratello Thomas sono toccate quelle che si occupano di cemento. I due settori sono complementari». Ma il giovane imprenditore – all’epoca ha meno di trent’anni – non è inesperto: «Ha già fatto esperienza in Sudamerica e in Sudafrica».

Nel 1976, quando prende in mano le redini di Eternit (ed era già nel cda dal 1973), «conosce abbondantemente il settore dell’amianto e sa che, tra l’altro, già dagli anni Cinquanta, è regolamentato benissimo dal Dpr 547 del 1955 e dal Dpr 303 del 1956: splendida normativa in tema di vita e salute dei lavoratori».

In quelle leggi sono indicate con chiarezza le disposizioni di tipo primario sugli impianti, di tipo secondario (qualora, dopo le prime, rimanga un residuo di rischio) con le protezioni individuali, di tipo informativo (ai lavoratori e non solo) e di tipo sanitario.

D’Amico afferma, documenti alla mano, che all’Eternit quelle norme sono state ampiamente disattese. Lo dimostrano anche le numerose prescrizioni impartite dall’Ispettorato del Lavoro, ignorate per anni dall’azienda.

«La sporcizia è diffusa e la polvere aleggia ovunque. E le mascherine? Lo stesso Robock, lo scienziato di fiducia di Schmidheiny, ebbe a commentare (e del suo dire si trova traccia scritta, ndr) che il tipo di mascherine fornite avevano solo una finalità psicologica per tener buoni i lavoratori».

Eppure, «il “ragazzo” di 28 anni sa tutto sull’amianto. E’ molto preparato al convegno di Neuss, convocato e presieduto da lui stesso; ai suoi massimi dirigenti parla (è tutto verbalizzato) della pericolosità e delle patologie. E li informa così bene e con dovizia di particolari che loro ne rimangono scioccati». E’ proprio questa la parola usata da Schmidheiny e annotata nella verbalizzazione del convegno.

«Ma il “ragazzo” che sa tutto, che a Neuss dimostra una grande consapevolezza sui rischi dell’amianto, che fa? Ha investito miliardi di lire, sì, ma per che fini? Quei soldi servirono per tenere in piedi la produzione – afferma D’Amico -. Ad esempio, nel ‘78 comprò la cava di Balangero…». Perché? Fu un investimento per la sicurezza? No, dice l’avvocata: «L’approvvigionamento di amianto alla fonte consentì di risparmiare un passaggio e aumentare i profitti».

E per la sicurezza e la salubrità nel posto di lavoro, che fa? «Nel ’77 – spiega l’avvocata – prende una decisione di estrema gravità: avvia una nuova lavorazione per recuperare gli scarti di produzione non solo di Casale, ma provenienti anche da tutti gli altri stabilimenti Eternit». E come avveniva? Tutti gli scarti arrivavano a Casale e venivano frantumati, 24 ore su 24, «prima entro il perimetro della fabbrica, poi, dopo le lamentele dei lavoratori, il lavoro di pala meccanica a cielo aperto fu spostato nell’area ex Piemontese, quasi prospiciente, ma fuori dallo stabilimento, più ancora verso la città…».

«I filtri, inoltre, erano inadeguati a trattenere le polveri; non c’era separazione, nei reparti, tra lavorazioni più e meno pericolose; le misurazioni ambientali erano approssimative». E la mensa? «Fu istituita solo nel 1979, prima i lavoratori mangiavano un panino seduti sui sacchi d’amianto». E la lavanderia? «Nel 1984 ancora si discuteva se realizzarla…».

Poi la voce si abbassa, per pudore, per dolore, per dare «le ultime pennellate rosso sangue su questa tragedia». D’Amico ricorda Paolo Bernardi. «Suo padre, ex operaio Eternit, morto di mesotelioma, suo fratello, pur non dipendente, morto dello stesso male. Quando Paolo scoprì di avere l’asbestosi, andò dal suo superiore per chiedere di essere spostato. E’ un uomo mite, Bernardi, garbato nei modi e nelle parole. “Dottore, disse, mi hanno trovato l’asbestosi. Sa, ho due bambini piccoli… Potrebbe spostarmi in un reparto meno polveroso?”». E quale fu la reazione? «”Bernardi, gli rispose il dottore, la vede la porta?”. Fu messo alla porta! Be’, anche Paolo è morto di mesotelioma».

D’Amico è lapidaria nella conclusione. Guarda in faccia i giudici: «Avete prova non solo delle condizioni igienico sanitarie non a norma nello stabilimento, ma anche del fatto che i pochi interventi furono inefficaci e attuati con la logica del risparmio massimo».

INQUINAMENTO FUORI DALLO STABILIMENTO

Ciò che è accaduto fuori dalla fabbrica è stato illustrato dall’avvocato Esther Gatti partendo dal profilo dell’imputato: «Questa è la storia di un uomo che, celando le conoscenze che aveva, ha cambiato la storia della collettività di Casale Monferrato: ha deciso per noi, tenendoci all’oscuro delle conoscenze che lui aveva. Ne ha informato soltanto i suoi massimi dirigenti, che rimasero scioccati, ma avremmo avuto diritto a essere scioccati anche noi per poterci difendere». Parla in prima persona plurale, perché Esther Gatti è lei stessa casalese. Come lo è il sindaco Federico Riboldi, presente all’udienza, insieme a Flavia Colombano, assessore di Ozzano (uno degli altri Comuni del circondario, non immuni dall’inquinamento da amianto, costituiti parte civile). Come lo sono, casalesi, i famigliari delle vittime, gli attivisti e i sindacalisti in aula. «Schmidheiny ha assunto decisioni scellerate al posto di questa collettività, tenendoci all’oscuro da informazioni che lui sapeva e che avrebbero cambiato la nostra storia». Perché Casale avrebbe avuto un’altra storia «se Schmidheiny non avesse deciso altro per noi!».

Racconta dello stabilimento abbandonato l’avvocata Gatti, «pieno di sacchi d’amianto, finestre rotte». Chi si è fatto carico di bonificarlo è stata la città di Casale: «Il sindaco Riboldi è venuto a spiegare quanto le bonifiche hanno pesato negli anni (e tutt’ora) sui bilanci comunali: si è dovuto scegliere se bonificare o se, ad esempio, costruire nuove scuole…».

Si è sempre data la priorità alle bonifiche, «è stata una lotta contro il tempo per impedire che ci fossero più morti di quelli che già ci sono. E, anzi, la città, attraverso l’ufficio comunale interamente dedicato a questa attività, ha dovuto inventarsi sistemi di bonifica fino ad allora sconosciuti, oltre a realizzare una discarica ad hoc per accogliere l’enorme quantità di manufatti d’amianto smantellati». Ma, ricorda Esther Gatti con indignazione, «l’imputato non si è mai offerto di contribuire: mai. D’altronde – chiosa il legale – fin da Neuss ha chiarito qual era la sua filosofia: “Chi si scusa si accusa”».

E Schmidheiny, a oggi, non ha ancora chiesto scusa. Sarebbe una svolta fondamentale se compiesse, finalmente, quel passo! Speranza improbabile? Illusione ingenua? Forse sì. Forse?

L’avvocata prosegue con «i ventoloni, causa di un inquinamento di portata dirompente: la polvere veniva buttata da dentro a fuori senza filtri».

E la frantumazione a cielo aperto nell’area ex Piemontese? E i magazzini in piazza d’Armi, con i camion che passavano per la città senza protezioni e coperture, e «ogni tanto i tubi cadevano pure a terra lungo il tragitto sfaldandosi»? E le tute e i grembiuli da lavoro che indossavano gli operai e le operaie uscendo dalla fabbrica, per tornare a casa, o fermarsi nei negozi, nel vicino mercato in piazza Castello? Quelle tute venivano lavate da mogli e madri: quante donne sono state condannate a morte perché non sono stati allestiti in fabbrica una lavanderia e degli spogliatoi adeguati? Quante!». A chi è presente in aula pare di veder scorrere, su uno schermo immaginario, i nomi conosciuti di tante donne.

E ancora: i camion che, nei cassoni scoperti, trasportavano rifiuti e scarti dalla fabbrica del Ronzone alla discarica Bagna oltre il ponte; e gli scarichi di acque reflue che uscivano dal canale dietro lo stabilimento e finivano nel fiume tanto da formare la famosa spiaggetta meta di molti casalesi. La spiaggetta, ricorda Esther Gatti, fu una delle priorità delle bonifiche: 12 mila metri cubi di terreno inquinato d’amianto. Senza contare che quelle acque fluirono anche nelle risaie.

Finito qui? No, affatto. Gatti ricorda la «scellerata cessione di polverino alla popolazione, tenuta all’oscuro del grave pericolo che comportava, così come per i feltri usati nelle cascine o nei sottotetti».

Poi l’affondo: «L’Eternit ha inciso sulla sorte di tanti cittadini che solo apparentemente non hanno avuto a che fare con lo stabilimento, perché la polvere d’amianto usciva dalla fabbrica ed entrava nel centro abitato, si diffondeva nelle strade e tra le case. Nessuno era al sicuro».

CERTEZZA DELLA DIAGNOSI

Ma quei 392 casi di mesotelioma sono diagnosi certe? «Lo sono sì: le scrupolose verifiche effettuate e illustrate dai consulenti della procura (Bellis, Mariani e già Betta), cui si sono aggiunte quelle di un luminare internazionale come il professor Papotti nominato dalle parti civili, sono ineccepibili e non lasciano dubbi» dice l’avvocato Giacomo Mattalia.

Ma i consulenti della difesa non hanno dato per certi tutti i 392 casi e hanno sollevato dubbi sulla attendibilità delle diagnosi. Perché? Il motivo principale: le diagnosi più datate non sono talora sorrette dalla verifica con i marcatori dell’immunoistochimica.

E senza immunoistochimica, a parere dei ct della difesa, quelle diagnosi potrebbero non essere stati mesoteliomi. E che cosa sarebbero stati? Metastasi di altri tumori, ad esempio. Così, senza specificare.

«L’anatomopatologo incaricato dalla difesa, professor Roncalli, ha degradato alcuni casi dal livello di certezza a quelli di possibilità o probabilità – ricorda Mattalia – perché sostiene che l’immunoistochimica non è bypassabile». Imprescindibile.

«Ma come! – stigmatizza Mattalia -. E allora gli studi di portata storica che lo scienziato Chris Wagner pubblicò nel 1960, in cui segnalava la cancerogenicità dell’amianto, sono da buttare via perché le diagnosi di mesotelioma (una trentina, in Sudafrica) su cui sono fondati vanno ritenute farlocche in quanto non supportate da immunoistochimica ma “solo” documentate istologicamente?».

Il legale scuote la testa: «L’evoluzione della tecnica è importante, ma non smentisce il passato».

Tanto più, rimarca l’avvocato, che «qui non stiamo parlando di diagnosi in modo teorico: si tratta di malati che sono stati curati per mesotelioma e le terapie adottate sono derivate da quella diagnosi, a volte riverificata da specialisti diversi. In nessuno c’è stata evidenza di patologie alternative: possibile che nessuno si sia accorto che non era mesotelioma?».

A proposito di certezza della diagnosi, tra l’altro, era stato fatto riferimento, durante l’esame dei consulenti, a uno studio (autori: Barbieri, Magnani, Mirabelli) in cui 175 casi di mesotelioma (pur diagnosticati in vita senza immunoistochimica) avevano trovato conferma nelle successive autopsie. Il lavoro fu pubblicato sull’autorevole rivista oncologica «Tumori».

NESSO CAUSALE E AUTOREVOLEZZA SCIENTIFICA

L’avvocato Laura Mara ha affrontato la questione del «nesso causale»: per pronunciare una dichiarazione di responsabilità nei confronti di un imputato occorre stabilire che, tra la condotta (di cui è accusato) e l’evento (che si è verificato a causa di quella condotta), ci sia un rapporto di causa-effetto.

In altre parole, per quanto riguarda questo processo, bisogna dimostrare che il comportamento di Stephan Schmidheiny ha provocato le 392 morti per amianto.

Come si è visto, la scienza è entrata nell’aula di giustizia: udienza dopo udienza è stato preponderante il confronto serrato tra consulenti della procura (e, concordi, quelli delle parti civili) e consulenti della difesa, perché la scienza è un perno fondamentale per stabilire appunto il nesso causale.

Ma gli scienziati sono sempre d’accordo? Condividono le stesse teorie? No.

E allora a quali tesi scientifiche i giudici, per decidere la sentenza, devono attenersi?

Laura Mara si è soffermata a lungo sulla cosiddetta «teoria della causalità scientifica» anche detta «legge di copertura». In base a questa teoria, «oggi accolta dalla giurisprudenza in modo prevalente, la condotta è causa dell’evento, quando, secondo la migliore scienza ed esperienza del momento storico, l’evento è conseguenza certa o altamente probabile di quella condotta». In altre parole, l’interrogativo si può riassumere così: l’evento (in questo caso le morti) si sarebbe o no verificato senza quella condotta (azioni o omissioni) dell’imputato?

Facendo riferimento al decennio 1976-1986, in cui Stephan Schmidheiny ha gestito personalmente l’Eternit, l’esposizione ad amianto ha influito sui casi di morte elencati nel capo di imputazione? Sì, a parere degli scienziati consulenti della procura, che sono convinti e sostengono la tesi multistadio o della dose aggiuntiva: cioè, le esposizioni iniziali (e non necessariamente la prima) hanno certamente un peso rilevante nella causa del mesotelioma, ma contano eccome pure quelle successive aggiuntive, che influiscono anche sull’anticipazione della morte.

I consulenti della difesa, invece, hanno messo in dubbio questa teoria scientifica e ne hanno opposto un’altra: quella secondo cui è la prima dose a generare la malattia, mentre quelle successive sono ininfluenti.

Come dovranno regolarsi i giudici che non sono scienziati? A chi credere?

«Riflettete sul peso reale degli studi portati alla vostra attenzione – ha esortato l’avvocata Mara -, tenendo conto che i consulenti della procura vanno considerati come pubblici ufficiali rispetto ai consulenti delle parti che tendono a perseguire delle finalità di altro genere. Lo dice la Cassazione, mica io! E tenete in conto la terzietà del consulente, verificando eventuali conflitti di interesse». E ha aggiunto: «Il vostro compito è quello di andare a verificare la tesi maggiormente accolta dalla comunità scientifica».

E’ un richiamo che trova sostegno in una cospicua giurisprudenza, di cui ha dato ampiamente conto Laura Mara: «Qui si è fatto il giochetto di insinuare dei dubbi, come se la comunità scientifica fosse spaccata a metà tra l’una e l’altra tesi. Non è così, non è così. Va verificata l’attendibilità degli esperti. Non solo: va accertato, ad esempio, chi ha finanziato certi studi portati a un processo. E va valutato, invece, quali siano gli studi che hanno trovato condivisione e approvazione della maggioranza della comunità scientifica internazionale in sedi autorevolmente riconosciute, come le Consensus Conferenze o in documentazioni qualificate come il “Quaderno della Salute 2012” del Ministero o la rivista “Epidemiologia e Prevenzione”».

IL DOLO EVENTUALE

«Questo è un processo unico. E’ una storia a sé che spero non si debba mai più ripetere». Il tono dell’avvocato Maurizio Riverditi è fermo mentre pronuncia parole lapidarie. E in che cosa consiste questo unicum? «Qui stiamo celebrando la riuscita del progetto di Schmidheiny: lui, già nel 1976, sapeva quello che stava facendo».

Tocca all’avvocato Riverditi, professore associato di diritto penale all’Università di Torino, affrontare la questione del dolo eventuale contestato all’imputato.

Il legale espone in premessa quello che, passo a passo, andrà poi ad argomentare: «Schmidheiny, consapevole della distanza temporale che necessariamente lo avrebbe separato dalle conseguenze dello scempio che aveva realizzato a Casale e dintorni, scelse deliberatamente di perseguire il profitto a discapito della salute delle persone, confidando che proprio il trascorrere del tempo e l’avanzare dell’età lo avrebbero posto al riparo da un giudizio di responsabilità delle sue azioni».

In altre parole, secondo l’avvocato Riverditi l’imprenditore svizzero era consapevole di scamparla proprio grazie alla lunga latenza degli effetti del suo agire (il mesotelioma si manifesta dopo molti anni dall’esposizione e, paradossalmente, funge da scudo protettivo per l’imputato).

Riverditi ritiene di poter «affermare con ragionevole certezza che Schmidheiny si fosse prospettato e avesse accettato l’idea che le morti (per le quali si celebra il processo, ndr) costituissero il prezzo da pagare per il vantaggio patrimoniale perseguito».

Che cosa sapeva il giovane capitano d’industria che prese le redini dell’Eternit? «Aveva padronanza della materia che governava, dei rischi che la caratterizzavano e delle conseguenze che avrebbero potuto causare». Lo disse chiaramente ai suoi collaboratori più alti in grado al convegno di Neuss nel giugno 1976: «La situazione attuale è una sfida che va a toccare l’eterno problema esistenziale: “Essere o non essere” (to be or not to be)». Ebbene, «l’imputato – afferma l’avvocato Riverditi – scelse lucidamente e liberamente di “essere”, ad ogni costo, anche al prezzo di dover causare la morte di coloro che egli aveva deciso di continuare a esporre all’inalazione della polvere d’amianto».

Ma quanto e cosa sapeva? Ad esempio, che in alcuni Paesi, come la Svezia, ma anche l’Inghilterra, sull’amianto c’erano controlli e norme più severe rispetto all’Italia dove si poteva invece ancora produrre tranquillamente; sapeva della regolamentazione Osha sulla diffusone delle fibre, ma, anche consigliato dal suo scienziato Robock, imponeva di richiamare la legislazione tedesca, meno restrittiva; sapeva della cancerogenicità dell’amianto e dell’allarme lanciato dallo scienziato Selikoff nel 1964 a New York («e nella “stanza segreta” all’Eternit fu trovata copia di un articolo del New York Times che ne scriveva»). Sapeva e disse chiaramente ai suoi dirigenti ciò che sapeva, ma li ammonì: «Dobbiamo renderci conto di una cosa: noi possiamo, anzi dobbiamo convivere con questo problema».

E come? «Negando l’esistenza di evidenze scientifiche, l’esistenza di un concreto pericolo per i lavoratori, così come per i loro famigliari e per gli abitanti delle zone limitrofe allo stabilimento». Il diktat: bisogna minimizzare i clamori e «raccontare bugie».

La ricostruzione dell’avvocato Riverditi è precisa: «L’imputato non solo protrasse la sua condotta per un decennio nella piena consapevolezza delle ricadute che ne sarebbero derivate per i lavoratori, per i loro famigliari e per la popolazione, ma lo fece programmando e ponderando con meticolosità le scelte comportamentali più idonee per nascondere l’evidenza della gravità del proprio agire». Con quale obbiettivo? «Il perseguimento del proprio vantaggio economico».

E, così, già nel 1976, pochi mesi dopo Neuss, venne redatto Auls 76, il «manuale della disinformazione» contenente le linee di condotta impartite ai dirigenti: «Non fatevi prendere dal panico. Cercate di avere buoni contatti con i mass media. Imparate la vostra lezione». La lezione, appunto, su cosa si deve dire, come si deve rispondere: il coro deve cantare lo stesso inno, senza sbavature. «Si fa la marachella e si raccontano le bugie per nasconderla» chiosa Riverditi che porta alcuni esempi di domande&risposte preconfezionate: 1 «Perché fino ad ora avete negato l’esistenza di questo pericolo?, «In realtà il rischio non era noto fino a pochi anni fa»; 2 «Cosa fate per proteggere i vostri lavoratori?», «Speciali abiti da lavoro vengono messi a disposizione (…), lasciati in fabbrica e la società si impegna ad eseguire la pulizia»; 3 «Cosa fate per proteggere i famigliari dei vostri lavoratori?», «Non c’è alcun pericolo per le famiglie»; 4 «E il pericolo per chi vive nei pressi dello stabilimento?», «Può essere esclusa in maniera assoluta l’esistenza di tale pericolo»; 5 «Perché usate ancora l’amianto blu che è particolarmente dannoso?», «Non ci sono dati scientifici che lo provino»; 6 «Non sarebbe più sicuro ed efficace bandire i prodotti di amianto-cemento?», «Può essere considerato senz’altro un materiale non pericoloso».

Non basta: nel 1984 Schmidheiny ingaggia un esperto di pubbliche relazioni, Guido Bellodi, affidandogli il compito (che svolge di sicuro almeno fino al Duemila) di accreditare una versione palesemente artefatta di quanto era stato fatto e di quanto sarebbe avvenuto. Il fallimento e la chiusura dello stabilimento nel 1986 erano già previsti. Bisognava gestire l’immagine.

Il professor Riverditi evoca campagne di bugie, mistificazioni, contatti e comunicazioni segrete tramite caselle di posta cifrate, il contenimento dell’informazione a livello locale, l’ingaggio di informatori, o spie che dir si voglia. E richiama anche un fatto preciso, successivo al fallimento: «Il 19 gennaio 1987, il curatore di Eternit spa ricevette la somma di 9 miliardi e mezzo di lire». Uno slancio di generosità nei confronti della collettività casalese? Be’, una nube offusca questo moto filantropico ed è contenuta in una clausola – richiamata da Riverditi – che «include nella transazione “le conseguenze del processo industriale e dei materiali in esso impiegati”». Per l’avvocato questa è un’ulteriore dimostrazione «della piena consapevolezza dei rischi connessi all’impiego dell’amianto nello stabilimento casalese», tanto da volerli tacitare con il versamento della somma di denaro. Ovvero: in cambio dei soldi offerti non si deve fare menzione su cosa e come si è lavorato all’Eternit.

E quindi? «L’imputato non si è trattenuto dalla condotta illecita e ha accettato la verificazione dell’evento» conclude il professor Riverditi. «Come è accaduto ad Auschwitz» aggiunge, annuendo lievemente col capo. «E poi è scappato. Proprio come è avvenuto ad Auschwitz».

L’accostamento a quella tremenda pagina di storia ha un precedente. Queste le parole del presidente della Corte d’Appello di Torino, Alberto Oggé, che giudicò Schmidheiny (e ribadì la sua responsabilità, con condanna poi cancellata in Cassazione non da un’assoluzione, ma dalla prescrizione) nel maxiprocesso per disastro doloso: «Neppure alla Conferenza di Wannsee (convocata da Goering, ndr) si disse che la “soluzione finale” consisteva nell’eccidio degli ebrei, ma che l’Olocausto fosse l’obbiettivo pur non dichiarato lo si comprende bene dalle condotte successive di Hitler e dei suoi».

L’avvocato Riverditi non ha dubbi sull’imputazione a Schmidheiny: «E’ un omicidio doloso».

RISARCIMENTI

Tutti i legali delle parti civili hanno consegnato alla Corte le memorie conclusive con le relative richieste risarcitorie. L’avvocato Alessandra Simone, dell’Avvocatura dello Stato, ha sottolineato «l’eccezionale gravità dei fatti che hanno profondamente scosso l’Italia intera, con effetti nocivi di spropositate dimensioni».

L’avvocato Alberto Vella ha rimarcato il ruolo di parte civile della Provincia di Alessandria, quale «ente territoriale esponenziale della comunità di Casale. L’ente ha come proprio compito quello di difendere e tutelare la vita dei suoi cittadini: qui la vita è stata danneggiata e colpita con l’uccisione di centinaia di persone».

E’ stata l’avvocata Laura D’Amico a delineare i parametri di riferimento oggettivi su cui fondare le richieste di risarcimento, sia per le persone fisiche sia per associazioni, organizzazioni ed enti. «E’ un compito arduo tradurre in denaro quanto vale quella sofferenza, quell’agonia…». La parola agonia è una lama affilata. Le parole si fanno sussurro: «E’ vero, non c’è mai denaro che paghi le sofferenze», ma «è anche attraverso il risarcimento che passa la risposta di giustizia che Casale attende, per la strage che ha subito e che non è finita. Ed è un segnale per l’imputato: ha voluto così tanto risparmiare sulla pelle delle persone? E allora sappia che la morte di quelle persone ha un valore anche economico».

E ha un valore lo sforzo enorme compiuto negli anni dai sindacati e dall’Afeva (Associazione famigliari e vittime amianto) che l’avvocata rappresenta: «Afeva ha fatto e continua a fare un lavoro gigantesco: ha alzato la voce contro l’amianto, si è fatta sentire in tutto il mondo e insiste, soprattutto con i giovani».

Venerdì 3 marzo, tra l’altro, la prima storica presidente dell’Afeva, Romana Blasotti Pavesi, strenua condottiera di questa battaglia di giustizia, cui l’amianto ha portato via il marito Mario, la figlia Maria Rosa, la sorella Libera e alcuni nipoti, compie 94 anni. Buon compleanno, Romana!

Cinquanta milioni di provvisionale: è questa la cifra che chiede l’avvocata Esther Gatti per il Comune di Casale. «Ogni cittadino vive ogni giorno con la paura di ammalarsi di mesotelioma, patologia dall’esito infausto. Questo dolore senza fine è un danno incalcolabile per il nostro Comune che rappresenta questa collettività». Gatti tutela anche i comuni del circondario, perché l’amianto non si è fermato nel perimetro casalese; sono: Ozzano, Rosignano, Cella Monte, Ponzano, Ticineto, Balzola, Morano, Pontestura, San Giorgio, Cereseto, Valmacca.

Richiama storie casalesi segnate dal mesotelioma: non ha bisogno di enfatizzare, perché la realtà è anche più cruda. Chi ne è colpito prova «una sofferenza che lo accompagnerà sempre». E allora l’appello finale alla Corte: «Nella sentenza che pronuncerete nel nome del popolo italiano e nel nome di quella parte del popolo italiano costituita dalla comunità casalese chiediamo venga riconosciuta la drammaticità che ha contraddistinto questa pagina dolorosa».

PROSSIME UDIENZE

Le udienze di venerdì 10 e mercoledì 29 marzo sono dedicate alle arringhe dei difensori Astolfo Di Amato e Guido Carlo Alleva. Poi è probabile che segua un intervallo prolungato prima delle repliche, cui seguirà la sentenza.

SENTENZA APPELLO CAVAGNOLO

La Corte d’Appello di Torino, nei giorni scorsi, ha riformato la sentenza di primo grado del filone Eternit Bis che riguardava due vittime di Cavagnolo: ha confermato la condanna per la vittima di asbestosi e ha invece assolto l’imputato Schmidheiny per la vittima di mesotelioma. Di conseguenza, anche la pena è stata ridotta da 4 anni a un anno e 8 mesi. Questo il dispositivo letto in aula. Interessante sarà capire le motivazioni del verdetto di cui si attende il deposito entro metà maggio (salvo proroghe).

BATTAGLIA IN BRASILE

Il Supremo Tribunal Federal del Brasile ha sancito il divieto di estrazione, industrializzazione e commercializzazione dell’amianto. La notizia è stata trasmessa in questi giorni da Fernanda Giannasi, la tenace pasionaria che da trent’anni guida la lotta contro l’amianto in Brasile, segnata anche da minacce personali e gravi tensioni. Merita ricordare che il contenuto del recente provvedimento brasiliano ricalca le parole di quella famosa delibera con cui il sindaco di Casale Riccardo Coppo vietò l’amianto a Casale nel 1987.

Non è un caso: Casale ha urlato forte, perché il grido di dolore e di ingiustizia superasse ogni confine e non rimanesse relegato «in ambito locale», come qualcuno aveva provato a fare. E quando le voci si uniscono, diventa potente e indomita la voce corale di quella che è stata definita la «multinazionale delle vittime dell’amianto».

* * *

Translation by Vicky Franzinetti

Monday February the 27th 2023 Eternit bis Hearing

By S. Mossano

The case of Casale Monferrato is unique, as is the suffering of the community, the agony of those who are diagnosed with mesothelioma and the lingering anxiety of those who fear that a cough or a suspected backache could turn into ‘that’ diagnosis. It is really a unique case. There is no other case comparable to the one experienced (and still being experienced) by the Casale community.

This was repeated by the plaintiff’s lawyers at the hearing on Monday, 27 February at the Eternit Bis trial held in the Court of Assizes in Novara. A unique unparalleled case in the world, illustrated from different points of view but which reach the same conclusion, a shared conclusion: ‘The defendant Stephan Schmidheiny is responsible for the voluntary murder (with possible malice) of the 392 people from Casale, listed in the indictment, who died of mesothelioma’. The lawyers for the plaintiffs (parties civiles) (victims’ families, associations, bodies and trade unions) believe they have proved, with complex arguments, that those mesotheliomas were caused by the consciously unwise spread of asbestos, used as raw material in Eternit’s production cycle. The Eternit where Stephan Schmidheiny was the last owner and manager.

THE PLAINTIFFS’ ARGUMENTS

The arguments, which are in line with the conclusions of public prosecutors Drs Gianfranco Colace and Mariagiovanna Compare (for whom the defendant deserves a life sentence without the benefit of mitigating circumstances and with the aggravation of day solitary confinement), were divided and illustrated in several chapters.

1) Pollution inside the plant

2) Pollution outside the factory

3) The certainty of the 392 mesothelioma diagnoses

4) The causal link between asbestos and mesothelioma, the validity of the multistage theory and the anticipation of the disease, and the hierarchy of authority of scientific theses

5) Malice/willfulness

6) The award of damages to individuals, entities, associations and trade unions, as well as the criteria to qualify for compensation

POLLUTION IN THE PLANT

“The Assizes Court is called upon to judge a tragic affair that goes beyond the borders of Casale, as well as the national and international ones”. Lawyer Laura D’Amico outlined the dramatic situation.

In front of her are the judges – president DR Gianfranco Pezone and the associate judge Dr Manuela Massino – and also the members of the jury, who have no specific legal skills. All together they will have to understand and evaluate, to deliver a verdict that takes into account the defendant’s conduct and the death of 392 people. Killed, according to the indictment.

A clear and precise reconstruction is necessary.

D’Amico began by introducing Stephan Schmidheiny: ‘He is a law graduate, so he started with a legal career. In 1976, he was formally appointed to manage the family’s asbestos companies around the world. His brother Thomas had the cement side. The two sectors are complementary’. But the young entrepreneur – under 30 years old at the time – was not inexperienced: ‘He had already gained experience in South America and South Africa’. In 1976, when he took over the reins of Eternit (and he had already been on the board of directors since 1973), ‘he was well acquainted with the asbestos sector and knew that, among other things, it had been well regulated since the 1950s by Presidential Decree 547 of 1955 and Presidential Decree 303 of 1965: splendid regulations on the life and health of workers’.

Those laws clearly set out the situation: primary provisions on installations, the secondary (if, after the former, a residual risk remains) with individual protections, the information type (to workers and others) and the specific health hazards. Lawyer D’Amico states, documents in hand, that at Eternit those regulations were largely disregarded. This is also demonstrated by the numerous prescriptions issued by the Labour Inspectorate, ignored for years by the company. “The dirt was widespread and dust hovered everywhere. And the masks? Dr Robock himself, Schmidheiny’s trusted scientist, commented (and there is written evidence of his saying, ed.) that the type of masks provided were only for psychological purposes to keep the workers quiet.” Yet, ‘the 28-year-old ‘boy’ knew everything about asbestos. He was very well prepared at the Neuss conference, which he himself convened and chaired; he speaks to his top managers (it is all on record) about the dangers and pathologies. And he informs them so well and in such detail that they were shocked’. Verbatim. And noted in the minutes of the conference. “What does this person who knows everything do, the person who in Neuss shows great awareness of the risks of asbestos? He invested billions of lire, yes, but for what purpose? That money was needed to keep production going,’ says D’Amico. ‘For example, in 1978 he bought the Balangero quarry…’. Why? Was it an investment for safety? No, says the lawyer: ‘Sourcing asbestos at source saved a step and increased profits.

And for safety and health in the workplace, what did he do? “In ’77,” explains the lawyer, “he made a very serious decision: he started a new process to recover production waste not only from Casale, but also from all the other Eternit plants. All the waste arrived at Casale and was crushed, 24 hours a day, ‘first within the perimeter of the factory, then, after the workers’ complaints, the open-air shovel work was moved to the former Piedmontese area, almost overlooking, but outside the factory, more towards the city…’.”The filters, moreover, were inadequate to trap dust; there was no separation, in the departments, between more and less dangerous work; environmental measurements were approximate.” And the canteen? “It was only established in 1979, before that workers ate a sandwich sitting on asbestos sacks”. And the laundry? ‘In 1984 they were still discussing whether to set it up…’.[…] D’Amico remembers Paolo Bernardi. ‘His father, a former Eternit worker, died of mesothelioma, his brother, although not an employee, died of the same disease. When Paolo discovered he had asbestosis, he went to his superior to ask to be moved. He was a mild man, Bernardi, polite in manner and words. ‘Look ,’ he said, ‘they found asbestosis. You know, I have two small children… Could you move me to a less dusty ward?”. And what was the reaction? “Bernardi,” the doctor replied, “do you see the door?! Well, Paolo also died of mesothelioma’. Lawyer D’Amico is lapidary in her conclusion. She looks the judges in the face: ‘You have proof not only of the substandard sanitary conditions in the plant, but also of the fact that the few interventions were ineffective and implemented with the logic of maximum savings.

POLLUTION OUTSIDE THE FACTORY

What happened outside the factory was illustrated by Lawyer Esther Gatti starting with the profile of the defendant: ‘This is the story of a man who, concealing the knowledge he had, changed the history of the community of Casale Monferrato: he decided for us, keeping us in the dark about the knowledge he had. He only informed his top management, who were shocked, but we would have had the right to be shocked too in order to defend ourselves’. She speaks in the first person plural, because Esther Gatti is herself from Casale. As is the mayor Federico Riboldi, present at the hearing, together with Flavia Colombano, councillor of Ozzano (one of the other municipalities in the district, not immune from asbestos pollution, who are plaintiffs). “Schmidheiny took wicked decisions in the place of this community, keeping us in the dark from information that he knew and that would have changed our history. Because Casale would have had a different history ‘if Schmidheiny had not decided something else for us!’ Lawyer Gatti tells of the abandoned plant, ‘full of bags of asbestos, broken windows. Those who took it upon themselves to reclaim it were the city of Casale: ‘Mayor Riboldi came to explain how much reclamation has weighed on municipal budgets over the years (and still does): a choice had to be made between reclamation or, for example, building new schools…’. Priority has always been given to reclamation, ‘it has been a fight against time to prevent more deaths than there already are. And, indeed, the city, through the municipal office entirely dedicated to this activity, had to invent hitherto unknown remediation systems, as well as creating an ad hoc landfill to accommodate the enormous quantity of dismantled asbestos artefacts. But Esther Gatti recalls with indignation, ‘the defendant never offered to contribute: never. On the other hand,’ explains the lawyer, ‘ever since Neuss he has made it clear what his philosophy was: ‘He who apologizes, accuses himself”. And Schmidheiny, to date, has still not apologised. It would be a major breakthrough if he finally took that step! Unlikely hope? Naive illusion? Perhaps so. Maybe? The lawyer goes on to say ‘the fans, the cause of disruptive pollution: dust was thrown from inside to outside without filters’. And the open-air crushing in the former Piemontese area? And the warehouses in the Piazza d’Armi, with the trucks passing through the city without protection and covers, and ‘every now and then the pipes would even fall to the ground on the way, falling apart’? And what about the overalls and work aprons that the workers wore as they left the factory, on their way home, or stopped at the shops in the nearby market in Piazza Castello? Those overalls were washed by wives and mothers: how many women were condemned to death because no proper laundry and changing rooms were set up in the factory? How many!”. Those in the courtroom seem to see the familiar names of so many women scrolling across an imaginary screen. And again: the lorries that, in uncovered skips, transported rubbish and waste from the Ronzone factory to the Bagna landfill beyond the bridge; and the sewage that came out of the canal behind the factory and ended up in the river, forming the famous spiaggetta (little beach), a destination for many of the people of Casale. The spiaggetta, remembers Esther Gatti, was one of the priorities of the reclamation: 12 thousand cubic metres of soil polluted with asbestos. Not to mention that those waters also flowed into the rice fields. Gatti recalls the ‘wicked transfer of powder to the population, kept in the dark about the serious danger it entailed, as well as the felts used in farmhouses or attics’. ‘Eternit affected the fate of many citizens who only apparently had nothing to do with the factory, because the asbestos dust came out of the factory and entered the town centre, spreading into the streets and among the houses. No one was safe’.

CERTAINTY OF DIAGNOSIS

Are those 392 cases of mesothelioma certain diagnoses? ‘They are: the scrupulous checks carried out and illustrated by the prosecution consultants (Drs Bellis, Mariani and formerly Betta), to which were added those of an international luminary such as Professor Papotti appointed by victims, are unexceptionable and leave no doubts,’ says lawyer Giacomo Mattalia. However, the defence consultants did not accept all 392 cases and raised doubts about the reliability of the diagnoses. Why? The main reason: older diagnoses are sometimes not supported by verification with immunohistochemistry markers. And without immunohistochemistry, in the defence expert witnesses’ opnion , those diagnoses might not have been mesotheliomas. And what would they have been? Metastases of other tumours, for example. ‘ Professor Roncalli the defence pathologist, , downgraded some cases from the level of certainty to those of possibility or probability,’ Lawyer Mattalia recalls, ‘because he maintains that immunohistochemistry cannot be bypassed. Unavoidable. ‘But how! – Mattalia stigmatises, ‘So the historic studies that scientist Chris Wagner published in 1960, in which he pointed out the carcinogenicity of asbestos, are to be thrown away because the diagnoses of mesothelioma (about thirty, in South Africa) on which they are based are to be considered fake because they are not supported by immunohistochemistry but ‘only’ documented histologically? The lawyer shakes his head: ‘Technical development is important, but it does not disprove the past. All the more so, the lawyer points out, that ‘here we are not talking about diagnoses in a theoretical way: we are talking about patients who were treated for mesothelioma and the therapies adopted were derived from that diagnosis, sometimes re-verified by different specialists. In none was there evidence of alternative pathologies: is it possible that no one realised that it was not mesothelioma?’. With regard to the certainty of the diagnosis, among other things, reference was made during the consultants’ examination to a study (authors: Prof Barbieri, Prof Magnani, and Dr Mirabelli) in which 175 cases of mesothelioma (although diagnosed in life without immunohistochemistry) had been confirmed in subsequent autopsies. The work was published in the authoritative oncological journal ‘Tumori’.

CAUSAL LINK AND SCIENTIFIC AUTHORITY

Lawyer Laura Mara addressed the issue of the ‘causal link’: in order to pronounce a statement of liability against a defendant, it must be established that there is a cause-and-effect relationship between the conduct (of which he is accused) and the event (which occurred as a result of that conduct). In other words, as far as this trial is concerned, it must be proven that Stephan Schmidheiny’s conduct caused the 392 asbestos-related deaths. As we have seen, science has entered the courtroom: hearing after hearing, there has been a fierce confrontation between the prosecution’s consultants (and, in agreement, those of the civil parties) and the defence consultants, because science is a fundamental pivot to establish precisely the causal link. Do scientists always agree? Do they share the same theories? No they don’t. So which scientific theories should judges adhere to when deciding the sentence? Laura Mara dwelt at length on the so-called ‘theory of scientific causality’ also known as the ‘law of hedging’. According to this theory, ‘now predominantly accepted by jurisprudence, conduct is the cause of the event when, according to the best science and experience of the historical moment, the event is a certain or highly probable consequence of that conduct’. In other words, the question can be summarised as follows: would the event (in this case the deaths) have occurred or not occurred without that conduct (actions or omissions) of the defendant? Referring to the decade 1976-1986, in which Stephan Schmidheiny personally managed Eternit, did exposure to asbestos influence the deaths listed in the indictment? Yes, in the opinion of the prosecution’s scientific consultants, who are convinced and support the multistage or additional dose thesis: that is, the initial exposures (and not necessarily the first) certainly have a significant weight in the cause of mesothelioma, but the subsequent additional exposures, which also influence the anticipation of death, also count. The defence consultants, on the other hand, cast doubt on this scientific theory and opposed another: that according to which it is the first dose that generates the disease, while subsequent ones are irrelevant.

How should the judges, who are not scientists, rule? Who to believe? ‘Think about the real weight of the studies brought to your attention,’ urged lawyer Mara, ‘bearing in mind that the prosecutor’s consultants are to be considered public officials as opposed to the parties’ consultants who tend to pursue other purposes. The Court of Cassation says so! And take into account the third party nature of the consultant, checking for possible conflicts of interest’. And he added: ‘Your task is to go and verify the thesis most widely accepted by the scientific community. This is a reminder that finds support in a considerable body of case law, which Laura Mara has given ample account of: ‘Here you have played the game of insinuating doubts, as if the scientific community were split down the middle between one thesis and the other. The reliability of the experts must be verified. Not only that: it must be ascertained, for example, who financed certain studies brought to trial. And it must be assessed, instead, which studies have been shared and approved by the majority of the international scientific community in authoritative places, such as the Consensus Conferences or in qualified documents such as the Ministry’s ‘Health Notebook 2012’ or the journal ‘Epidemiology and Prevention”.

POSSBLE INTENT

“This is a unique trial. It is a story in itself that I hope will never be repeated’. The tone of lawyer Maurizio Riverditi is firm. And what is this uniqueness? “Here we are celebrating the success of Schmidheiny’s project: in 1976, he already knew what he was doing”. It is the turn of lawyer Riverditi, an associate professor of criminal law at the University of Turin, to address the question of the possible intent contested against the defendant. The lawyer sets out in the introduction what, step by step, he then goes on to argue: ‘Schmidheiny, aware of the distance in time that would necessarily have separated him from the consequences of the havoc he had wrought in Casale and the surrounding area, deliberately chose to pursue profit at the expense of people’s health, trusting that the very passage of time and advancing age would have sheltered him from a verdict making him liable for his actions’. In other words, according to lawyer Riverditi, the Swiss entrepreneur was aware that he would escape liability precisely because of the long latency of the effects of his actions (mesothelioma manifests itself many years after exposure and, paradoxically, acts as a protective shield for the defendant). Prof Riverditi believes that he can ‘affirm with reasonable certainty that Schmidheiny had envisaged and accepted the idea that the deaths (for which the trial is being held, ed.) constituted the price to be paid for the patrimonial advantage pursued’.

What did the young captain of industry who took the reins of Eternit know? “He had a mastery of the matter he governed, of the risks involved and the consequences they could cause. He made this clear to his senior staff at the Neuss conference in June 1976: ‘The current situation is a challenge that touches on the eternal existential problem: “To be or not to be”‘. Well, ‘the defendant,’ says lawyer Riverditi, ‘lucidly and freely chose to “be”, at any cost, even at the price of having to cause the death of those whom he had decided to continue to expose to the inhalation of asbestos dust’. How much and what did he know? For example, that in some countries, such as Sweden, but also England, there were stricter controls and regulations on asbestos than in Italy, where it could still be produced quietly; he knew about the [US] OSHA regulation on the spread of fibres, but, also advised by his scientist Robock, he was recalling the less restrictive German legislation; he knew about the carcinogenicity of asbestos and the alarm raised by the scientist Selikoff in 1964 in New York (‘and in the ‘secret room’ at Eternit, a copy of a New York Times article writing about it was found’). He knew and clearly told his managers what he knew, but warned them: ‘We must realise one thing: we can, indeed we must, live with this problem’. ‘By denying the existence of scientific evidence, the existence of a real danger for the workers, as well as their families and the inhabitants of the areas surrounding the plant’. He minimised the rumours and ‘told lies’. Lawyer Riverditi’s reconstruction is precise: ‘The defendant not only continued his conduct for a decade in full awareness of the repercussions it would have for the workers, their families and the population, but he did so by meticulously planning and weighing up the most suitable behavioural choices to conceal the evidence of the seriousness of his actions’. With what objective? “The pursuit of his own economic advantage”. And so, as early as 1976, just a few months after Neuss, Auls 76, the ‘disinformation manual’ was drawn up, containing the lines of conduct given to managers: ‘Do not panic. Try to have good contacts with the media. Learn your lesson’. The lesson, in fact, on what one should say, how one should respond: the choir must sing the same hymn, without blunders. “You do the mischief and tell lies to hide it,” Riverditi chides, bringing some examples of pre-packaged questions & answers: 1 “Why have you denied the existence of this danger until now? “2 “What do you do to protect your workers?”, “Special work clothes are made available (…), left in the factory and the company undertakes to carry out the cleaning”; 3 “What do you do to protect the families of your workers?”, “There is no danger for the families”; 4 “What about the danger for those who live near the factory? “5 “Why do you still use blue asbestos, which is particularly harmful?”, “There is no scientific data to prove this”; 6 “Wouldn’t it be safer and more effective to ban asbestos-cement products?”, “It can certainly be considered a non-hazardous material”. As if this was not enough: in 1984 Schmidheiny hired a public relations expert, Guido Bellodi, entrusting him with the task (which he certainly carried out until at least the year 2000) of crediting a blatantly fabricated version of what had been done and what would happen. The bankruptcy and closure of the plant in 1986 was already foreseen. The image had to be managed. Professor Riverditi evokes campaigns of lies, mystifications, contacts and secret communications through encrypted mailboxes, the containment of information at local level, the hiring of informers, or spies as you like. And he also recalls a precise fact, following the bankruptcy: ‘On 19 January 1987, the receiver of Eternit spa received the sum of 9 and a half billion lire. An outburst of generosity towards the Casale community? Well, a cloud clouds this philanthropic motion and it is contained in a clause – recalled by Riverditi – that ‘includes in the settlement “the consequences of the industrial process and the materials used in it”‘. For the lawyer, this is a further demonstration of ‘full awareness of the risks associated with the use of asbestos in the Casalese plant’, so much so that he wanted to silence them by paying the money. In other words: in exchange for the money offered, no mention should be made of what and how work was carried out at Eternit. ‘The defendant did not hold back from unlawful conduct and accepted the occurrence of the event,’ Professor Riverditi concludes. ‘As happened at Auschwitz,’ he adds, nodding his head slightly. “And then he escaped. The juxtaposition to that terrible page of history has a precedent. These were the words of the president of the Turin Court of Appeal, Alberto Oggé, who judged Schmidheiny (and reiterated his responsibility, with a conviction later quashed in the Court of Cassation not by acquitting him, but for a technicality linked to the statute of limitations) in the trial for wilful environmental disaster: “Not even at the Wannsee Conference [convened by Goering, ed.]was it said that the “final solution” consisted in the massacre of the Jews, but that the Holocaust was the objective, even if not declared, is well understood by the subsequent conduct of Hitler and his men”. Lawyer Riverditi has no doubts about Schmidheiny’s indictment: ‘It is wilful murder’.

COMPENSATION

All the lawyers of the civil parties delivered their final briefs to the court with the relevant claims for compensation. Lawyer Alessandra Simone, of the Avvocatura dello Stato (representing the State) , stressed “the exceptional gravity of the facts that have deeply shaken the whole of Italy, with harmful effects of disproportionate dimensions”. Lawyer Alberto Vella emphasised the role of the Province of Alessandria as plaintiff, as the ‘ for the community of Casale. The task of our Authority is to defend and protect the lives of its citizens: here, lives have been damaged and affected with the killing of hundreds of people’. Lawyer Laura D’Amico had outlined the objective benchmarks on which to base claims, both for individuals and for associations, organisations and entities. “It is an arduous task to translate into money what that suffering, that agony, is worth,” she said. The word agony is a sharp blade. ‘It is true, there is never money to pay for suffering’, but ‘it is also through compensation that the response of justice that Casale awaits passes, for the massacre it has suffered and which is not over. And it is a signal to the defendant: did he want to save so much? Then know that the death of those people also has an economic value. And the enormous effort made over the years by the trade unions and by Afeva (Associazione famigliari e vittime amianto – Association of Asbestos Victims and Families), which the lawyer represents, has a value: ‘Afeva has done and continues to do a gigantic job: it has raised its voice against asbestos, it has made itself heard all over the world and insists, especially with young people’.

On Friday 3 March, Afeva’s first historical president, Romana Blasotti Pavesi, the strenuous leader of this battle for justice, to whom asbestos took away her husband Mario, daughter Maria Rosa, sister Libera and some grandchildren, turns 94. Happy birthday, Romana!

Fifty million as a downpayment for damages: this is the amount that lawyer Esther Gatti is asking for from the municipality of Casale. ‘Every citizen lives every day with the fear of falling ill with mesothelioma, a pathology with an inauspicious outcome. This never-ending pain is an incalculable damage for our municipality that represents this community’. Lawyer Gatti also defends the surrounding municipalities, because asbestos did not stop in the Casalese boundaries; they are: Ozzano, Rosignano, Cella Monte, Ponzano, Ticineto, Balzola, Morano, Pontestura, San Giorgio, Cereseto, and Valmacca.

She recalls Casalese stories marked by mesothelioma: she does not need to emphasise, because the reality is even starker. Those affected experience ‘a suffering that will always accompany them’. The final appeal to the Court: ‘In the sentence that you will pronounce in the name of the Italian people and in the name of that part of the Italian people constituted by the community of Casale, we ask that you recognise the drama that has marked this painful page’.

NEXT HEARINGS

The next hearings Friday, on March the 10th and Wednesday, March the 29th are for defence counsel Lawyers Astolfo Di Amato and Guido Carlo Alleva. Then there is likely to be an extended break before the replies, which will be followed by the judgment.

CAVAGNOLO APPEAL SENTENCE

In recent days the Turin Court of Appeal, reviewed the sentence of the Court of Turin in the Eternit Bis case involving two Cavagnolo victims: it confirmed the verdict for the asbestosis victim and instead acquitted the defendant Schmidheiny for the mesothelioma victim. Consequently, the sentence was also reduced from four years to one year and eight months. It will be interesting to understand the grounds for the verdict, when the motivations will be made public by mid-May (unless extended).

Grazie Silvana

Grazie Silvana Mossano, il lavoro che sta conducendo è esemplare, sempre accurato e chiaro. Complimenti.

Il commento lo hai già scritto tu cara Silvana e anche molto bene. Attendiamo fiduciosi la sentenza augurandoci che sia Giusta nel rispetto dei nostri cari defunti a cui rivolgiamo sempre i nostri cuori e preghiere.

La strage continua, continuiamo a morire. Nuove diagnosi, io invece ricomincio la chemio e spero, spero che nessuno si ammali più. Grazie Silvana Mossano

Brava!!! Ancora grazie Slvana per il tuo costante, grande e puntuale lavoro!!!

Posso solo ribadire che senza le tue dettagliate e comprensibili argomentazioni sul disastro amianto, i cittadini di Casale non avrebbero l’opportunità di comprendere senza ombra di dubbio questo disastro che ci accompagnerà ancora purtroppo per molto tempo. Grazie Silvana.

Grazie Silvana

Grazie cara Silva!