SILVANA MOSSANO

Reportage udienza 11 aprile 2022

Sotto accusa tutte le aziende del Casalese o, meglio, sotto il sospetto di avere, in qualche modo o in qualche misura, utilizzato l’amianto non come materia prima, ma come «supporto» nei diversi cicli produttivi.

Parola del chimico igienista Danilo Cottica, con un curriculum di peso: oltre che professore a contratto nelle università di Pavia e Brescia, e docente in un master all’ateneo di Padova, è stato presidente dell’Associazione italiana degli igienisti industriali e dell’organismo che coordina a livello mondiale le Associazioni di Igienisti Industriali dei diversi paesi.

E’ uno dei consulenti della difesa di Stephan Schmidheiny, l’imprenditore svizzero accusato, nel processo Eternit Bis in Corte d’Assise a Novara, dell’omicidio doloso di 392 casalesi, morti a causa dell’amianto.

Cottica ha esordito ricordando che l’amianto, «per le sue elevate qualità, è stato ampiamente usato in tutto il mondo, sia come “materia prima” (manufatti di «eternit», ndr), sia come “materiale ausiliario” in diversi impianti produttivi, sia come “agente di protezione” (indumenti, guanti e così via)». Il consulente ha indicato i molteplici campi in cui il minerale veniva impiegato: filati, cordami, feltri, isolanti, vernici e spray, coperte, guanti, guarnizioni, indumenti ignifughi, talco, cartoni, coibentazioni, sipari teatrali, tavoli da stiro, filtri, elementi frenanti, rivestimenti di stufe, casseforti, porte antifiamma… Un lungo elenco.

Dopo la premessa generale, Cottica si è addentrato nel territorio casalese, mostrando una pubblicazione del 1999 dedicata alla storia e all’architettura, all’arte e alle tradizioni, ai personaggi e all’economia del Monferrato. In uno dei capitoli, è pubblicata una tabella delle principali aziende del territorio. Il consulente le ha elencate praticamente tutte, abbinandole agli specifici settori: refrigerazione, costruzioni meccaniche, metallurgia, legno, gomma e plastica, tessile e abbigliamento, alimentare, cementerie, edilizia e commercio. Poi, ha ipotizzato che, in alcune di queste ditte, potrebbe esserci stato un impiego «ausiliario» di amianto in materiali di supporto e apparecchiature.

Il consulente ha chiarito il suo obbiettivo: affermare, in generale, che «l’amianto a Casale non veniva usato solo all’Eternit, ma in molti altri settori». Da qui la successiva considerazione che «la possibile esposizione» delle persone che si sono ammalate di mesotelioma, può essere avvenuta «anche in ambienti diversi» dall’Eternit. Il dottor Cottica ha ammesso di non avere prova e certezza che in tutte le aziende citate siano stati usati materiali o strumenti in cui era presente amianto, «ma – ha azzardato – non è escluso, è un’ipotesi valida come le altre, è una supposizione».

L’Eternit è stata, invece, l’unica fabbrica del territorio ad aver impiegato l’amianto come materia prima, per 80 anni. In che modo?

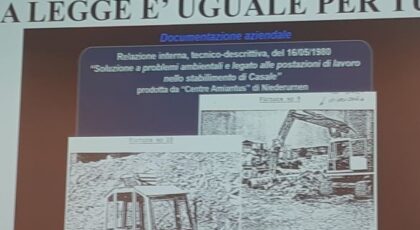

Un altro consulente della difesa, l’ingegner Giuseppe Nano, docente al Politecnico di Torino e di Milano, e autore di numerose pubblicazioni, ha riferito che la società, a partire dalla prima metà degli anni Settanta, aveva investito parecchio nell’ammodernamento degli impianti, facendo molti interventi per garantire maggiore sicurezza. E a giudizio del consulente tecnico «qualsiasi intervento innovativo e di miglioramento della produzione», anche se non specificatamente finalizzato alla sicurezza ha di per sé «riflessi positivi per l’ambiente, riducendo la polverosità».

Nano ha poi aggiunto che «gli interventi sono stati fatti secondo le regole dell’epoca», utilizzando «le migliori tecnologie» che «hanno prodotto una diminuzione dell’inquinamento». Anche l’Ispettorato del lavoro, in una relazione del 1987, aveva annotato che «l’Eternit, all’inizio del 1974, aveva avviato un vasto piano di ristrutturazione e ammodernamento degli impianti». Un piano che, secondo il parere del consulente, è stato realizzato nel rispetto delle «buone pratiche» dell’epoca, con «il supporto fornito dal Gruppo Svizzero agli stabilimenti italiani».

A questo proposito è stato citato il professor Robock, «responsabile dell’attività di consulenza nel campo delle misure tecniche di prevenzione, della misurazione degli agenti di rischio e dell’aggiornamento normativo». Robock, dopo un sopralluogo alla fabbrica di Casale a gennaio/febbraio 1976, aveva fatto osservazioni su alcune criticità, indicando precise soluzioni migliorative, ad esempio sull’aspirazione e sui sistemi di ventilazione.

Incrociando l’analisi di più fonti, il professor Nano ha ricostruito il passaggio della lavorazione da secco a umido, l’evoluzione dal metodo di «aspirazione generale» (cioè i «ventoloni» a parete che espellevano l’aria dei reparti verso il lato del canale Lanza) a quello di «aspirazione locale» con il posizionamento di «cappe» per ogni utensile, che dovevano captare la polvere nel punto in cui si generava. Più nessun pericolo, a suo giudizio, per l’operaio, «sempre distante dall’utensile».

Altro intervento rilevante segnalato dal consulente è stato l’impianto di trattamento delle acque reflue; allo scopo, era stato acquistato un terreno di oltre tremila metri quadrati di cui si dà conto «in un documento del 29 ottobre 1976». «Prima -, ha sottolineato – non si faceva il trattamento delle acque». In realtà non lo si faceva anche perché non era obbligatorio: lo è diventato con l’entrata in vigore della legge Merli, proprio nel 1976, a maggio, cinque mesi prima dell’acquisto dell’area. Quindi l’Eternit dovette costruire per forza il depuratore, entrato in funzione nel 1980.

Dopo il raffronto tra immagini scattate nello stabilimento nel 1978 e altre del filmato «Luce» risalente agli anni Trenta, Nano ha ribadito che «all’Eternit si attuavano le migliori pratiche operative per quell’epoca», con la conseguenza che «era diminuito il livello di esposizione alle fibre e il Gruppo svizzero si era autodeterminato a contenere la concentrazione di fibre al di sotto dei parametri di riferimento».

Infine, l’ingegner Nano ha aggiunto che, comunque, «nell’84 la strategia del Gruppo Eternit era quella di sostituire il più rapidamente possibile l’amianto con fibre alternative immettendo sul mercato nuovi prodotti che fossero privi di amianto».

Riflessioni

Giova inquadrare il momento storico: il 1984 è l’anno in cui l’Eternit chiese l’amministrazione controllata e, due anni dopo, il fallimento. Leo Mittelholzer, alto dirigente e ultimo amministratore delegato di Eternit in Italia, testimoniò al Maxiprocesso di Torino che, effettivamente, erano stati interpellati i concorrenti di Eternit sul mercato italiano ed era stato prospettato un patto per produrre un materiale alternativo, eliminando così l’impiego di amianto. Le preoccupazioni dell’opinione pubblica si facevano sempre più pressanti e insidiose per il settore. L’accordo non si trovò, perché la trasformazione avrebbe comportato un costo eccessivo, soprattutto per i produttori minori. Quindi l’Eternit, per non perdere fette di mercato, decise di continuare a sua volta la produzione tradizionale in Italia. E’ l’epoca in cui l’allora sindaco Riccardo Coppo, dopo le disattese promesse svizzere sull’imminente impiego di fibre alternative, disse: «Qui ci prendono in giro».

Comunque, i consulenti fino a ora esaminati hanno riferito una positiva condotta del Gruppo svizzero che si comportò, come hanno riferito i consulenti Stefania Chiaruttini e Luca Minetto, da buon azionista di riferimento: garantì supporto finanziario al Gruppo italiano, pur rispettandone l’autonomia, e fece congrui investimenti che si rifletterono positivamente sulla sicurezza e sull’ambiente.

E, poi, ci sono stati tutti gli interventi tecnici di cui è stato dato conto nell’udienza di lunedì 11 aprile. Abbiamo appreso che, addirittura prima che l’imputato Stephan Schmidheiny assumesse personalmente la gestione dell’Eternit, il Gruppo svizzero, già guidato dal padre Max, nel 1973, 1974 e 1975 aveva attuato un imponente ammodernamento degli impianti e delle metodologie. Viene da domandarsi, allora, come mai, nonostante queste cospicue migliorie, Stephan Schmidheiny (che nel settore si muoveva già da alcuni anni) abbia sentito la necessità di convocare i massimi dirigenti al convegno di Neuss del 1976 per rappresentare una situazione fortemente preoccupante. «Catastrofale» (citazione testuale). Alcuni di quegli stretti collaboratori uscirono dalla riunione «choccati» (idem: testuale).

Altra riflessione, che prende spunto dalle valutazioni del professor Cottica: ha indicato quali erano, in generale, i settori in cui poteva essere impiegato l’amianto se pur non come materia prima e ha ipotizzato che, anche nelle fabbriche casalesi di vari comparti, quegli impieghi di supporto potessero essere in uso. E, allora, perché a Casale e dintorni si registra un’incidenza di malati di mesotelioma e morti ben superiore che altrove? Le fabbriche meccaniche e metallurgiche, di tessuti e abbigliamento, di alimentari e del legno e così via, non esistevano in molti altri importanti poli industriali italiani?

Quanto ai tetti di cemento-amianto su case e palazzi, su capannoni e garage, di cui i difensori hanno chiesto conto ad alcune decine di famigliari delle vittime, sì, c’erano, così come del resto in ogni località d’Italia, perché, come ha sottolineato il professore, se ne faceva largo uso. Ma, allora, perché a Casale ci sono molte più vittime che nelle altre città?

Infine, è vero che il mesotelioma è caratterizzato da una lunga latenza, anche di decenni; la difesa tende a far ricadere le responsabilità di incontrollate diffusioni delle fibre su chi aveva gestito l’Eternit in passato, prima degli anni Settanta, cioè prima che tutte le migliorie di cui si è dato conto fossero state adottate. Ma, allora, perché si è passati da un numero di 15-25 nuove diagnosi di mesotelioma all’anno a una cinquantina? Tutti contaminati in epoche datate?

Si farà di sicuro chiarezza su questi interrogativi, altrimenti resterebbe la sensazione che si tende semplicemente a insinuare nei giudici dubbi generici.

PROSSIME UDIENZE

Il processo in Corte d’Assise a Novara ora viene sospeso e riprende tra un mese circa.

I difensori Astolfo Di Amato e Guido Carlo Alleva hanno annunciato quali saranno i prossimi consulenti. Questa la scaletta delle date: il 16 maggio sarà terminato l’esame del professor Cottica e, subito, dopo, il professor Nicotera, direttore scientifico del Centro nazionale per le malattie neurodegenerative di Bonn; il 23 maggio, è il turno del professor Marsh, che arriva dagli Stati Uniti, esperto di biostatistica ed epidemiologia all’Università di Pittsburgh, in Pennsylvania; il 30 maggio controesame dei consulenti Nicotera, Nano e Cottica.

Nella foto in apertura, un gruppo di attivisti storici presidiano ogni udienza del processo Eternit Bis fuori dall’aula di Novara. Al momento, il processo si svolge ancora senza pubblico, in seguito all’ordinanza del presidente della Corte d’Assise Gianfranco Pezzone, causa covid.

Translation by Vicky Franzinetti

April the 11th 2022 Eternit Hearing

by Silvana MOSSANO

All the companies in the Casale area are guilty or rather, under suspicion of having used asbestos not as a raw material, but in their production cycles, in some way or to some extent.

This is what the hygiene chemist Prof Danilo Cottica said. His CV is impressive: besides being a fixed term professor at the universities of Pavia and Brescia, and a lecturer in a Master’s program at the University of Padua, he was president of the Italian Association of Industrial Hygienists and of the organization that coordinates the Associations of Industrial Hygienists globally. He is one of the defense expert witnesses for Stephan Schmidheiny, the Swiss entrepreneur accused of the willful murder of 392 people from Casale killed by asbestos, now being heard at the Eternit Bis trial at the Court of Assizes in Novara,.

Prof Cottica began by recalling that asbestos, ” has been widely used all over the world, both as “raw material” (Eternit products, ed.), and as “auxiliary material” in various production plants, and as “protective agent” (clothing, gloves and so on) because of its qualities “. The expert witness indicated the many fields in which the mineral was used: yarns, ropes, felts, insulation, paints and sprays, blankets, gloves, seals, fireproof clothing, talc, cardboard, insulation, theater curtains, ironing boards, filters, braking elements, stove linings, safes, fireproof doors… A long list. After a general introduction, Prof Cottica detailed the Casale area, showing a 1999 publication dedicated to the history and architecture, art and traditions, characters and economy of Monferrato. In one of the chapters, a table of the main companies in the area is published. The consultant listed practically all of them, matching them to specific sectors: refrigeration, mechanical construction, metallurgy, wood, rubber and plastic, textiles and clothing, food, cement factories, construction and trade. He speculated that, in some of these firms, there may have been “auxiliary” use of asbestos in materials needed for production and equipment.

The expert witness illustrated his position: in general, “asbestos in Casale was not only used at Eternit, but in many other industries”. Hence the subsequent consideration that “the possible exposure” of people who developed mesothelioma, may have occurred “also in environments other” than Eternit. Dr. Cottica admitted that he had no proof and certainty that in all the companies mentioned have been used materials or tools in which asbestos was present, “but – he ventured – it can’t be ruled out, my hypothesis is as good as any other, it is a hypothesis”.

Eternit was, however, the only factory in the area to have used asbestos as a raw material, for 80 years.

Another consultant of the defense, Professor Engineer Giuseppe Nano, at the Polytechnic of Turin and Milan, and author of numerous publications, said that the company had invested heavily in the modernization of plants since the early Nineteen Seventies, by taking steps to ensure greater safety. In the expert witnesses opinion, “any innovative intervention and improvement of production, even if not specifically aimed at safety” had a “positive impact for the environment, reducing dustiness”.

Prof Nano then added that “the interventions were made according to the rules of the time,” using “the best technologies” that “produced a decrease in pollution.” In a 1987 report, even the Labor Inspectorate, had noted that “Eternit, at the beginning of 1974, had initiated a vast plan to restructure and modernize the plants.” A plan which, in the consultant’s opinion, was carried out in accordance with the “best practices” of the time, with “the support provided by the Swiss Group to the Italian plants”.

Dr Robock was mentioned as “responsible for consulting activities in the field of technical prevention measures, measurement of risk agents and regulatory updating”. After an inspection at the Casale plant in January/February 1976, Dr Robock had made observations on some critical features, indicating precise improvement solutions, for example on the suction and ventilation systems. Cross referencing several sources, Professor Nano reconstructed the passage from dry to wet processes, the evolution from the “general suction” method (i.e. wall-mounted fans aka ventoloni that expelled the air from the workshops on the side of the Lanza Canal) to that of “localized suction” with the positioning of “hoods” for each tool, which had to capture the dust at the point where it was generated. In his opinion there was no danger for the workers who were “always at a distance from the tool”. Another important point raised by the expert concerned the wastewater treatment plant; a plot of land of over three thousand square meters had been purchased for this purpose, and is accounted for “in a document dated October 29, 1976”. “Previously-, he underlined – there had been no water treatment “. In fact, there was none because it was not mandatory: it became compulsory with the entry into force of the Merli Law in May 1976, five months before the purchase of the area. At that point Eternit had to build the purification plant, which became operational in 1980. After comparing images taken at the plant in 1978 with other images of the Luce institute film dating back to the Thirties, Nano reiterated that “Eternit implemented the best operating practices for the time”, with the result that “the level of exposure to fibers had decreased and the Swiss Group had managed to contain the concentration of fibers below the required threshold levels”. Finally, Professor Nano added that, in any case, “in 1984, the Eternit Group’s strategy was to replace asbestos with alternative fibers as quickly as possible by placing new products on the market that were asbestos-free”.

Remarks

It is useful to frame events in time: 1984 is the year in which Eternit filed for receivership and, two years later, for bankruptcy. Leo Mittelholzer, a senior executive and the last managing director of Eternit in Italy, testified at the Turin maxi-trial that, in fact, Eternit’s competitors on the Italian market had been approached and there had been an agreement to produce an alternative material, thus eliminating the use of asbestos. The concerns of public opinion were becoming increasingly pressing and insidious for the sector. No agreement was found, because the changes would have involved an excessive cost, especially for smaller producers. In order not to lose market share, Eternit decided to continue its traditional production in Italy. That was when the then Mayor Riccardo Coppo, said after the unfulfilled Swiss promises on the imminent use of alternative fibers,: “They are making fun of us”. However, the expert witnesses heard so far have reported positively conduct of the Swiss Group that behaved, as reported by Stefania Chiaruttini and Luca Minetto, as a good reference shareholder: it guaranteed financial support to the Italian Group, while respecting its autonomy, and made appropriate investments that reflected positively on safety and the environment.

What did the expert witnesses say in this latest hearing on Monday, April 11. We learned that, even before the defendant Stephan Schmidheiny personally took over the management of Eternit, the Swiss Group, already led by his father Max, in 1973, 1974 and 1975 had implemented massive modernization of its plants and methods. One wonders, then, why, in spite of these conspicuous improvements, Stephan Schmidheiny (who had already been working in the sector for some years) felt the need to summon the top managers to the 1976 Neuss conference to represent a highly worrying situation. “Catastrophic” (verbatim quote). Some of those close collaborators came out of the meeting “shocked” (idem: verbatim).

Another remark stemming from Professor Cottica’s witness: he indicated which were the industries in which asbestos could be used, even if not as a raw material, and hypothesized that, even in the Casale factories of various sectors, what the additional uses could be. So one wonders why in Casale and its surroundings there is a much higher incidence of mesothelioma patients and deaths than elsewhere? Were there no mechanical and metallurgical, textile and clothing, food and wood plants elsewhere in other major Italian industrial centers? As for the asbestos-cement roofs on houses and buildings, on sheds and garages, of which the defense lawyers asked dozens of victims’ families about, yes, there were, as well as in every other place in Italy, because, as the professor pointed out, it was widely used. But, then, why are there more victims in Casale than in other cities?

Finally, it is true that mesothelioma has a long latency, even decades; the defense tends to blame the uncontrolled spread of fibers on those who had managed Eternit in the past, before the Nineteen Seventies, that is, before all the improvements that have been taken into account had been adopted. But, then, why did we go from a number of 15-25 new diagnoses of mesothelioma per year to about fifty? All of them contaminated in the distant past?

These questions need to be answered, otherwise the feeling would remain that they are just trying to sow doubts in the minds of the Court (Judge and Jury).

NEXT HEARINGS

The trial in the Court of Assize in Novara is now suspended and will resume in about a month.

The defense lawyers Astolfo Di Amato and Guido Carlo Alleva have announced the next consultants. This is the list of dates: on May the 16 th Professor Cottica will conclude and, immediately after, he will be followed by Professor Nicotera, scientific director of the National Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases in Bonn; on May the 23rd it will be the turn of Professor Gary Marsh, who comes from the United States, an expert in biostatistics and epidemiology at the University of Pittsburgh, in Pennsylvania; on May the 30th , cross for Professors Nicotera, Nano and Cottica.

Consulente di Schmidheiny insinua sospetti su altre aziende casalesi

Una cosa è certa i “soldi” e tanti la proprietà ne ha tantissimi e si serve del denaro per pagare onorari superlativi ad avvocati di spessore che facendo il loro dovere tirano l’acqua al proprio mulino . Ma anche Afeva sta impegnando fior di Avvocati. Auguriamoci che alla fine sia fatta Giustizia sui nostri cari defunti a cui rivolgiamo una preghiera nel periodo di Quaresima , Pasqua di Resurrezione.

Grazie tante Silvana per le preziose sintesi delle udienze. Grazie anche per le osservazioni e per i richiami alla realtà rispetto alle consulenze della difesa, in particolare all’evoluzione dei dati epidemiologici….

Buona Pasqua! augurandoci rafforzi la nostra Resistenza e Resilienza !

Dici proprio bene, Silvana: ‘Si farà di sicuro chiarezza su questi interrogativi, altrimenti resterebbe la sensazione che si tende semplicemente a insinuare nei giudici dubbi generici’.

Leggo tanta amarezza sottesa alle tue parole, perché la sensazione di essere presi in giro, come ai tempi del Sindaco Coppo, resta davvero forte.

Il diritto di ogni imputato a difendersi è indiscutibile, il dovere di ogni avvocato è farlo in un modo efficace, ma il diritto nostro e di tutti quelli che non ci sono più, al di là della condanna e dei risarcimenti, è sentir l’affermazione della verità, sarebbe l’unico modo per avere consolazione.

Le parole come quelle ascoltate a Novara sembrano invece offenderla e prederla a calci, la verità.