SILVANA MOSSANO

Reportage udienza del 4 ottobre 2021

La polvere, all’Eternit, era quasi una sorta di «elemento genetico» della fabbrica.

Era dentro ed era fuori: lo attestano i racconti dei testimoni diretti (ad esempio, Nicola Pondrano, ex lavoratore e poi dirigente sindacale, e Giovanna Patrucco, figlia della panettiera che aveva il negozio poco distante dallo stabilimento), i verbali di ispezione dell’Ispettorato del lavoro, le relazioni tecniche (l’Istituto di Medicina del lavoro di Pavia, del professor Michele Salvini consulente per conto del giudice del lavoro di Casale, dei consulenti aziendali Occella e Clerici), le decine di verbali con le richieste insistenti e ripetitive, su cui insistette per anni il consiglio di fabbrica, oltre che le centinaia di rilievi eseguiti dal Sil (l’organismo istituito dall’azienda per occuparsi di sicurezza e igiene) e altresì le relazioni del medico scienziato Klaus Robock, responsabile del laboratorio di Neuss, pagato dal gruppo svizzero proprietario dell’Eternit.

E, in questa polvere, era contenuta fibra di amianto: sia crisotilo (amianto bianco) sia crocidolite (amianto blu).

«Si può dire che era polvere velenosa?» domanda il pubblico ministero Gianfranco Colace al consulente Luca Mingozzi, funzionario dell’Arpa Piemonte al Centro regionale Amianto. La risposta è lapalissiana: «Non sono un medico, ma so che l’amianto è cancerogeno».

L’udienza di ieri, lunedì 4 ottobre, al processo Eternit Bis, è stata occupata dall’esame di Mingozzi che, affiancato dal collega Angelo Salerno, era stato incaricato dalla procura di analizzare la cospicua documentazione: «Illustri le condizioni in cui versava lo stabilimento di Casale e dica quali furono le ricadute sui lavoratori e anche sull’ambiente esterno alla fabbrica» ha esordito la pm Mariagiovanna Compare (insieme a Colace, sostiene l’accusa nel processo in cui Stephan Schmidheiny è chiamato a rispondere, davanti alla Corte d’Assise di Novara, dell’omicidio volontario, con dolo eventuale, di 392 casalesi morti a causa dell’amianto).

PRODUZIONE E PERSONALE

Dopo aver evidenziato in una cartina la dislocazione in via Oggero (quartiere Ronzone) dell’area produttiva («in attività dal 19 marzo 1907 al 30 novembre 1985, cui il 4 giugno 1986 è seguì la dichiarazione di fallimento»), con la suddivisione dei vari capannoni («ciascun reparto era un locale unico, senza paratie protettive»), Mingozzi si è soffermato sull’ordine di grandezza della produttività («nel 1979 all’Eternit di Casale venivano impiegate 83 tonnellate al giorno di amianto, che arrivavano dal Canada in sacchi di plastica e da Balangero in sacchi di carta») e sull’impiego di personale. A questo proposito, giova riportare alcuni dati: a dicembre 1976 i dipendenti erano 1126, tra operai, impiegati e dirigenti; nel 1977 erano già diminuiti a 963, a 859 nel 1978, a 823 nel 1980, a 602 nel 1982, a 478 nel 1984 fino ai 377 del 1985, momento della interruzione dell’attività produttiva. I numeri sembrano confermare l’intenzione del gruppo svizzero, già emerso da alcuni documenti acquisiti al processo, di portare a esaurimento il settore amianto, perché sempre meno remunerativo (già se n’era allontanato il gruppo belga) anche a causa di un’avanzata e diffusa consapevolezza sui rischi della fibra per la salute.

CONDIZIONI IGIENICHE

Poi il consulente ha richiamato le testimonianze dirette (alcune sono state scartate dalla Corte, perché tecnicamente non utilizzabili nel processo) e i tredici verbali compilati dall’Ispettorato del lavoro, con decine di prescrizioni all’Eternit di Casale riguardanti problematiche igieniche: dai ventoloni senza filtri che buttavano la polvere contaminata fuori dalla fabbrica, alle motoscope acquistate alla fine degli anni Settanta che, di fatto, non sostituirono del tutto le scope perché i mezzi meccanici non arrivavano dappertutto e quindi il lavoro andava rifinito a colpi di ramazza, alle mascherine fornite ma inadeguate e comunque non obbligatorie (lo stesso Robock scrive in una relazione che «il potere di queste mascherine ha quasi esclusivamente un effetto psicologico» e ne suggerisce un altro modello), agli indumenti di lavoro dati in dotazione dall’azienda ma senza una lavanderia per poterli lavare (con diffusione, quindi, di polvere per le strade e portati a casa per il bucato), alla mancanza di un doppio armadietto personale per i lavoratori, a docce che «non invogliavano al loro utilizzo» («che vuol dire?» domanda il presidente della Corte, Gianfranco Pezone; la risposta: «Erano poche, sporche, senza porte, malfunzionanti, con acqua fredda»), alle modalità di apertura dei sacchi di amianto.

Situazioni che, appunto, anche Robock riscontra durante sopralluoghi a Casale.

E la proprietà che cosa ha fatto per porre rimedio alla situazione?, domanda la pm Compare.

RIDUZIONE DELLE POLVERI?

«Alcuni investimenti alla fine degli anni Settanta sono stati fatti – riconosce Mingozzi -, come ad esempio il passaggio della lavorazione da secco (molto più pericolosa) a umido e l’installazione del mulino Hazemag, ma non si è risolto il rischio di esposizione alle polveri contenenti amianto».

Ma c’era chi faceva meglio? E’ l’interrogativo che, articolato in più domande, hanno posto nel controesame, i difensori Astolfo Di Amato e Elisa Surbone (in sostituzione di Guido Carlo Alleva): «C’erano, in quegli anni, modelli migliori cui fare riferimento? C’erano, all’epoca, norme precise – hanno insistito – che imponevano livelli minimi di concentrazione delle fibre nell’aria?».

Mingozzi ha richiamato il Dpr 303 del 1956: «E’ vero che non indicava dei livelli minimi di concentrazione delle fibre – ha ammesso, rispondendo alle richieste di chiarimento dei difensori – ma era una precisa scelta legislativa, che si poneva l’obbiettivo di abbattere, alla fonte, qualunque polvere, anche quelle non pericolose». A maggior ragione, tenendo conto della qualità delle polveri. E la qualità di quelle dell’Eternit era caratterizzata dalla presenza di amianto.

Ne hanno chiesto conto anche i legali di parte civile. Laura D’Amico ha posto l’attenzione sulla volatilità delle polveri, anche in considerazione della friabilità dei manufatti: Mingozzi ha ribadito la pericolosità sia in presenza della materia prima sfusa nei sacchi, aperti senza precauzioni, sia nell’effettuazione di operazioni particolari: taglio, molatura, perforazione, tornitura eccetera. Laura Mara ha domandato se «furono adottate adeguate tecniche di aspirazione, ad esempio in corrispondenza delle varie apparecchiature o di specifiche lavorazioni più soggette a sollevare polvere»; la risposta: «No, non c’erano aspiratori per tutte le postazioni di lavoro». Da una relazione dell’Ispettorato del lavoro emerge che erano «molte le situazioni in cui gli impianti esistenti, finalizzati a minimizzare la diffusione / dispersione di polveri e fibre all’interno degli ambienti di lavoro erano ritenute inadeguate».

E FUORI DALLA FABBRICA?

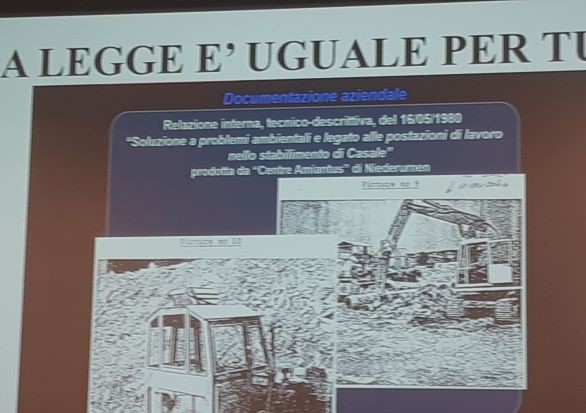

Oltre ai «ventoloni», che sputavano aria sporca sul lato verso il fiume, il consulente ha richiamato l’attenzione sull’area Rba, cosiddetta Ex Piemontese, dove venivano frantumati gli scarti di lavorazione che sarebbero stati successivamente sfarinati nel mulino Hazemag. «Era l’unico nel Nord Italia e, per un certo periodo, anche l’unico in Italia – ha spiegato Mingozzi – . Pertanto arrivavano a Casale gli scarti di lavorazione di tutti gli stabilimenti Eternit italiani. Nell’area a cielo aperto, sul lato opposto allo stabilimento, ma più vicina alla città, con un cingolato queste montagne di scarto secco venivano pestate e sminuzzate, un lavoro continuo ventiquattr’ore su ventiquattro». In merito a questa attività, Robock, in una relazione tecnica del 16 maggio 1980, scriveva; «Non dovrebbe essere consentito frantumare i cascami in uno spazio aperto senza un sistema a spruzzo di acqua. Se le nubi di polvere vengono spinte dal vento nelle zone limitrofe, si potrebbe verificare un intervento da parte delle autorità di sicurezza, e questo causerebbe numerosi problemi». A chi? «Allo proprietario dello stabilimento».

Dopo la frantumazione all’Ex Piemontese, il materiale, a bordo di un motocarro, veniva trasferito allo stabilimento prospiciente e riversato nel mulino che lo riduceva in polvere. Di questa, ne veniva impiegata una piccola percentuale da aggiungere alla mescola del nuovo processo produttivo per realizzare manufatti (lastre o tubi).

Oltre alla segnalazione dei rischi della frantumazione a cielo aperto, sempre in una relazione fatta dall’azienda stessa il 30 gennaio 1980, era stato posto l’accento sullo «scarico continuo (nel Po, ndr)durante il ciclo produttivo settimanale con una portata di 3000/4000 litri al minuto di acqua con sostanze in sospensione e sedimentabili, più lo scarico saltuario durante la pulizia settimanale», scarico definito «molto al di fuori dei limiti consentiti dalla nuova disciplina per quanto riguarda le sostanze in sospensione». Mingozzi ha conteggiato un’uscita di materiale secco, dentro gli scarichi, pari a 20 tonnellate alla settimana. Questo scarico diretto nel Po determinò la formazione di una «penisola – ha riferito il consulente – che restringe l’alveo del fiume. Penisola che i casalesi, per anni, associarono all’appellativo ludico-ricreativo di «spiaggetta».

PROSSIMA UDIENZA

Venerdì 8 ottobre saranno esaminati altri quattro consulenti della procura: Turcotti, Belci, Patricelli e Grassi, che illustreranno la dislocazione dello stabilimento rispetto al centro abitato e le caratteristiche geologiche del terreno.

Nella foto in apertura, le ruspe con cui venivano frantumati a cielo aperto gli scarti di «eternit» nell’area dell’Ex Piemontese (il documento è stato reperito tra quelli in dotazione all’azienda)

* * *

Traduzione a cura di Vicky Franzinetti

SILVANA MOSSANO

October 4th 2021 hearing

At the Eternit plant, dust was almost part of the facotory’s DNA. It was inside and outside: this was described by the witnesses’ accounts – for example, Nicola Pondrano, a former worker and then trade union leader, and Giovanna Patrucco, daughter of the baker who had her shop not far from the plant, by the labour inspectors’ reports, the technical reports ( Professor Michele Salvini consultant for the Casale Labour Courts , from the Institute of Occupational Medicine of Pavia, the company consultants Occella and Clerici, dozens of reports with insistent and repetitive requests, by the Works Council for years, as well as the hundreds of surveys carried out by Sil (the department set up by the company to deal with safety and hygiene) and the reports by the medical scientist such as Klaus Robock, Director of the Neuss laboratory, paid for by the Swiss group that owned Eternit. This dust contained asbestos fibre: both chrysotile (white asbestos) and crocidolite (blue asbestos).

“Can we describe it as poisonous dust?” Public Prosecutor Gianfranco Colace asked expeert witness Luca Mingozzi, an official of Arpa Piemonte (The Environmental Agency) at the regional Asbestos Centre. The answer is clear: ‘I am not a doctor, but I know and knew that asbestos caused cancer’.

Dr Mingozzi was heard on Monday the 4th of October, at the Eternit Bis trial, along with his colleague Angelo Salerno who had been asked by the prosecution to analyse the extensive documentation: “Illustrate the conditions in which the Casale plant was operating and say what the effects were on the workers and also on the environment outside the factory”, began the prosecutor Mariagiovanna Compare (who is the PP with Colace in the trial in which Stephan Schmidheimy is called to answer, before the Court of Assizes of Novara, for the voluntary murder , with possible wilfulness, of 392 people from Casale who died because of asbestos).

During direct, Mingozzi pointed to the production site on a map in via Oggero (Ronzone district) (“operating from 19 March 1907 to 30 November 1985, till bankruptcy was filed on June the 4th 1986“), with the various workshops : “Each department was a single room , without protective bulkheads“), dwelled on the order of magnitude of productivity: “in 1979 Eternit Casale used 83 tonnes of asbestos per day, which arrived from Canada in plastic bags and from Balangero in paper bags” and on the use of staff. Numbers were important: in December 1976 there were 1,126 employees, including workers, clerks and managers; in 1977 numbers had declined to 963, to 859 in 1978, to 823 in 1980, to 602 in 1982, to 478 in 1984 and to 377 in 1985, when production ceased. The figures seem to confirm the Swiss group’s intention to shut down, which had already emerged from some documents in the trial, to bring discontinue the asbestos branch, because it was becoming less and less profitable (the Belgian group had already left) and also because of an advanced and widespread awareness of the health risks of the fibre.

The expert witness recalled the direct testimonies, some were not accepted by the Court for technical reasons and the thirteen reports by the Labour Inspectorate, with dozens of orders issued against the Casale Eternit plant on hygiene related breaches: the fans without filters that spewed the contaminated dust out of the factory, to the electric sweepers purchased at the end of the 1970s that, in fact, never completely replaced hand brooms because the mechanical means could not reach nooks and crannies and therefore the work had to be finished by hand, to the inadequate and in any case not compulsory masks. Dr Robock himself wrote in a report that “the power of these masks is almost exclusively psychological ” and suggests another model, the overalls supplied by the company but without a laundry to wash them (thus spreading dust in the streets and taken home for washing), the lack of a double personal locker for workers, showers that ‘did not encourage their use’ (‘what does that mean? “Gianfranco Pezone, president of the Court, asked: “They were few, dirty, without doors, malfunctioning, with cold water“), and the way in which the asbestos sacks were opened. Robock also found this during his inspections at Casale. And what did the owners do to remedy the situation? Asked Dr Compare. Some investments were made at the end of the Seventies,” said Mingozzi, “such as switching the processing from dry (much more dangerous) to wet and installing the Hazemag mill, but the risk of exposure to asbestos-containing dust was not eliminated”.

However, were there any better models to refer to? This is the question that, in fact one of many questions, defence lawyers Astolfo Di Amato and Elisa Surbone (replacing Guido Carlo Alleva for the hearing) asked in cross-examination: ‘In those years were there better models to refer to? Were there precise standards at the time that imposed minimum levels of fibre concentration in the air?”. Mingozzi did not give a clear-cut answer; he quoted and insisted, Presidential Decree 303 of 1956: ” It’s true that it didn’t indicate minimum fibre concentration levels,” he admitted, answering the defence team’s requests for clarification, “but it was a precise choice of the legislation, with the aim of reducing any dust at source, even non-dangerous dust. All the more so, taking into account the quality of the dust which in Eternit’s case meant asbestos. The plaintiffs’ lawyers also crossed. Laura D’Amico drew attention to the volatile nature of the dust, also in view of the friability of the products: Mingozzi reiterated the danger both in the presence of the raw material loose in the bags, opened without any precaution, and in the performance of particular operations: cutting, grinding, drilling, turning, etc.. Plaintiffs’ lawyer Laura Mara asked whether “adequate suction (aspiration) devices were adopted, for example in correspondence with the various pieces of equipment or specific processes that were more prone to raising dust“; the answer: “No, there were no suction (aspiration) devices for all the work stations”. A report by the Labour Inspectorate shows that there were ‘many situations in which the existing systems designed to minimise the spread/dispersion of dust and fibres within the workplace were inadequate’.

What about outside the factory?

In addition to the “fans”, which spewed out dirty air on the side facing the river, the witness drew attention to the Rba area, known as Ex Piemontese, where the waste was crushed and then ground into flour in the Hazemag mill. For a time it was the only one in northern Italy and, also the only one in Italy,” explained Mingozzi. This meant that waste from all the Eternit plants in Italy was brought to Casale. In the open-air area, on the opposite side of the plant, but closer to the city, with a caterpillar those mountains of dry waste were crushed and shredded, a continuous work around the clock“. Robock wrote in a technical report dated May 16th, 1980 on this activity: ‘ Waste should not be crushed in an open space without a water spray system. If the dust clouds are blown by the wind into the surrounding areas, the health and safety authorities might intervene, and this would cause numerous problems“. To whom? ‘To the owner of the plant’.

After being crushed at the Ex Piemontese, the material was transferred by lorry to the plant opposite and poured into the mill, which ground it to powder. A small percentage was used to add to the mix of the new production process to make products (slabs or pipes).

In addition to pointing out the risks of open-air crushing, a report drawn up by the company itself on 30 January the 30th 1980 drew attention to the “continuous discharge (into the River Po, Note.) during the weekly production cycle with a flow rate of 3000/4000 litres per minute of water containing suspended and sedimentable substances, plus the occasional discharge during weekly cleaning”, a discharge defined as “well outside the limits allowed by the new regulations as regards suspensions“. Mingozzi referred to a 20 tonne per week output of dry material into the drains. This direct discharge into the River Po created a ‘peninsula’, the witness reported, narrowing the riverbed. For years it was known in Casale as spiaggetta the little beach and it became a leisure or recreational spot.

NEXT HEARING

On Friday October the 8th , four other expert witnesses of the Prosecution will be examined: Turcotti, Belci, Patricelli and Grassi, who will illustrate the location of the plant in relation to the town and the geological feautures of the area.

Lawyer Laura D’Amico

At the hearing of October the 4th, Dr. Mingozzi , the Prosecutor’s expert witness, of the Regional Environmental Protection Agency, was examined. Dr MIngozzi reconstructed the environmental and hygienic conditions inside the Eternit plant in Casale Monferrato, with particular reference to the presence of asbestos.

After examining the documents produced by the prosecutor, drawn up by the Health and Safety agency , the company, trade union sources, as well as the numerous testimonies of former Eternit employees heard as witnesses in the first trial, the expert highlighted the critical conditions in the various areas of the plant, all of which were characterised by the indiscriminate presence of asbestos fibres, free to airborne due to the inefficiency, if not the absence, of adequate dust collection systems at source, particularly dangerous dry working, the absence of protective equipment appropriate to the asbestos risk, as well as the lack of information and training of workers. All this in violation of Italian criminal law on safety in the workplace.

Udienze tecniche , dietro ogni documento c’è una persona . Questa è la gravità ! Andiamo Avanti . Buona serata e Grazie Paolo